Who is the most courageous player in NHL history to be a member of the Hockey Hall of Fame?

One way to answer the question is to take a Hall of Famer and compare the number of times he survived serious injuries and still managed to play at a high level for Cup-winning teams.

Pronovost earned berth in Hockey Hall of Fame with courage, skill

Five-time Cup-winning defenseman excelled despite injuries during 20 seasons with Red Wings, Maple Leafs

By

Stan Fischler

Special to NHL.com

Perhaps the NHL's best combination of skill and courage was

Marcel Pronovost

, a defenseman who excelled for the Detroit Red Wings and Toronto Maple Leafs in a career that ran from 1950 to 1970. That's two decades worth of injuries, comebacks -- and five Stanley Cups, four with Detroit and the last, in 1967, with Toronto.

"Marcel's courage could match anyone's in the League," said Jack Adams, himself a Hall of Famer. It was Adams, as Detroit's general manager, who signed Pronovost to a contract with the Red Wings.

"Marsh's problem was the fact that he was overshadowed by our more flashy players like Gordie Howe, Ted Lindsay and Red Kelly."

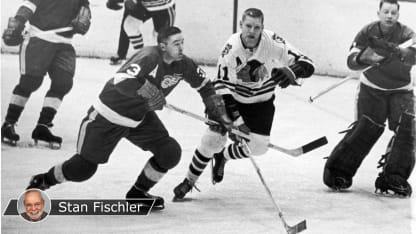

Here's one episode that provides insight into Pronovost's devil-may-care style. The Red Wings were playing the Chicago Blackhawks when he sped through the neutral zone, heading for the net. The only problem: Two Chicago defensemen were waiting for him at the blue line. "I decided there was only one move," he said. "Bust through the middle."

Pronovost wasn't thinking about getting hurt. He never did. He eyed the two-foot gap between defensemen, pushed the puck ahead and leaped into the opening.

Too late. The defensemen sent Pronovost headfirst over their shoulders. In that split second, he looked down, saw the puck below him and swiped at it. He missed and had to settle for a three-point landing on his left eyebrow, nose, and cheek.

© B Bennett/Getty Images

A few minutes later he was lying on a dressing room table with ice bags on his nose and forehead. His skull looked like it had come in second-best in a bout with a bulldozer. His nose was broken, and his eyebrow required 25 stitches. "And my cheekbones," Pronovost recalled, "felt as if they were pulverized." Which they were -- cracked like little pieces of china.

"What hurt most," he said, "was that I had to miss the next two games. As for the injuries, I didn't think twice about them."

That was nothing unusual for Pronovost. "To me," he once said, "accidents were as common as lacing on skates."

His stitches and fractures ran into triple figures, and his sprains were so numerous he eventually lost count of them. If a doctor ever made a bone-by-bone examination he'd swear on a stack of gauze pads that Pronovost was the most injured man in sports.

Talk about courage: During the Detroit-Chicago Stanley Cup Final in 1961, Pronovost played four games on a badly cracked ankle. He would arrive at the arena on crutches, play the game, then put his foot back in the cast. "Marsh played on guts alone, nothing else," one teammate said.

Pronovost's toughness was obvious from NHL debut in the 1950 Stanley Cup Playoffs. He was called up after being named rookie of the year with Detroit's Omaha farm team in the United States Hockey League and helped the Red Wings defeat the Toronto Maple Leafs in a seven-game Stanley Cup Semifinal before outlasting the New York Rangers in a seven-game Final. At 19 years old, Pronovost already had his name engraved on the Stanley Cup.

He expected to make the Red Wings as a regular when he came to training camp in the fall of 1950. Instead, he was blasted right out of the NHL. During a rush, he tried bisecting the defense pairing of Leo Reise and Bob Goldham. Instead, all three fell to the ice and Goldham's stick creased Pronovost's face, leaving him with a fractured cheekbone. But after 34 injury-free games at Indianapolis, the Red Wings called him up and he became as much a fixture in Detroit as General Motors.

"Once I got back to the NHL I began to enjoy myself," he said. "I only missed a single game in the 51-52 season. I was going along fine the next year until a January game against the Montreal Canadiens."

© B Bennett/Getty Images

Games between the Canadiens and Red Wings always seemed to be on the brink of total warfare. "I'd play those guys for nothing, just so I could go out on the ice and tear a piece out of them," Detroit captain Ted Lindsay once said. The Canadiens weren't any more kindly disposed toward one of their biggest rivals.

On this night, Pronovost stole the puck at center ice early in the game and raced toward the Montreal net. "There was only one man with a chance to catch me," he remembered, "Maurice Richard."

Richard swerved suddenly towards center to nail his man.

"Out of the corner of my eye I saw him coming," Pronovost said. "But I wasn't concentrating on him as much as I was on the goal. I was about to shoot when a hunk of lumber smashed against my jaw. I was out cold." Richard had hacked Marcel's mouth, broken his jaw and pushed in four front teeth.

"Funny, I remember skating off the ice under my own power but I can't remember whether I finished the game or not. That night I traveled to Detroit by train. I didn't do much sleeping. I didn't eat any breakfast either. When I got home my wife said my face swelled up so much I looked like a mummy. I guess the worst part of it was that I missed a few teeth."

Unlike many players, Pronovost had no fear of a visit to the dentist's office; he went there as calmly as he'd visit the corner grocery. "I was never bothered by the dentist," he said. "I guess, for me, it was like anything else in life -- some people are bothered and others aren't."

What did bother Pronovost was missing a game. So imagine how he felt in March 1954, when a collision sidelined him for nine games, among the most he ever missed. It happened in a game against Chicago. Marcel was racing down right wing when his skate hit a rut in the ice.

"Lee Fogolin, the big Chicago defenseman, was standing there, waiting to belt me," he said. "But I fooled him. Unintentionally, of course."

© Denis Brodeur/Getty Images

Derailed by the rut, Pronovost plunged headfirst into Fogolin's shoulder, breaking the fourth dorsal vertebra in his back.

"At first I had spasms and couldn't move my arms," he said. "I went to the dressing room, felt better, came back and finished the game. Day after, I went bowling. When I got home I couldn't move. The doc said it was my back, so I had to sit out nine games." He didn't miss that many games in a season again until 1965-66.

A shoulder separation proved that a clean play can be as damaging as a dirty one. Late in December 1957, the Red Wings were playing Chicago. Although Pronovost had heard about Blackhawks rookie Bobby Hull, he underestimated the kid's strength. "When he bore down on me," Pronovost said, "I thought I'd be able to hit him straight up and stop him. He fooled me and went low." The point of Hull's elbow dug into Pronovost's chest and rode up to his shoulder. "It was a clean play," he admitted admiringly. "I wish I'd have thought of that!"

Pronovost's durability amazed everyone.

"The way he dropped in front of shots," a Detroit writer once said, "you'd think a puck would have blasted right through his ribs and out the other side." Actually, this nearly happened in a game against Montreal, when Canadiens center Jean Beliveau took a shot that nearly drove the puck through Marcel's eye. As Beliveau teed up his shot, Pronovost fell to his knees about 10 feet away. The puck hit his right eye, sending him to the ice.

"They turned the lights out on me that night," he said with a laugh. "But I guess I was lucky. The puck hit me flat. If it had hit me on the sharp side I would have lost the eye. All I had was some hemorrhaging."

He was even luckier in a game against the Rangers at Madison Square Garden. With time running out and the Red Wings hanging on to a one-goal lead, Andy Bathgate, New York's best forward, sent a cross-ice pass to Dean Prentice. Pronovost dived and intercepted the puck, but the momentum carried him into the wake of another speeding Rangers skater, whose skate blade sliced into his cheek. It severed a vein and barely missed cutting his eye.

I once asked Pronovost whether he was afraid of dropping in front of shots, noting that, "It seems like the most dangerous play in hockey."

Pronovost said it wasn't as dangerous as it looked. "Most of the time you get the puck in the ribs or the soft part of the stomach," he said. "It would sting, but if I fell at the right time and the right place I'd get hit by the puck before it got too much power. Of course, if I didn't do it right, I'd be in trouble."

"Didn't that play make you nervous?"

He thought for a few seconds and then delivered the perfect reply:

"No more than crossing the street."