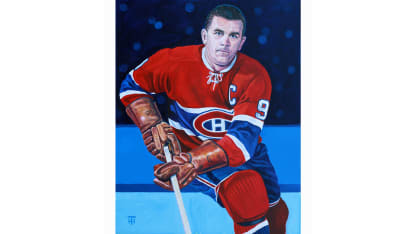

"When I first arrived in Montreal, the Canadiens may have been managed by Frank Selke, but they were really Joseph Henri Maurice Richard's team," Beliveau wrote in his 1994 autobiography "My Life in Hockey."

"The Rocket was the heart and soul of the Canadiens, an inspiration to us all, especially to younger French-Canadians who were rising through the ranks. He was man and myth, larger than life in some ways, yet most ordinary human in others. …

"The timing of his contribution, from the war years through to 1960, coincided with that period in Quebec when a tidal wave of change was sweeping aside more than 300 years of history.

"As players, however, we saw Maurice in simpler, more immediate terms. He embodied something which would rub off on many of his teammates, something which would carry us to five straight championships by the end of the decade. Quite simply, Maurice Richard hated to lose with every fibre of his being. Everyone picked up on this - his teammates, his opponents, the media, and the hockey public at large."

Like Beliveau after him, Richard put his individual statistics second to his team. He viewed his intangibles as things more important than his deadly aim with the puck, making him one of the greatest players of all time, and a 1961 Hall of Fame inductee.

"What counted above all is that I worked hard," he said in one his final interviews. "I set a good example. I helped other players, I went out with them. And when anyone didn't want to go to a banquet or ceremony of some sort, I went in his place."

To this day, the Rocket's aura still burns radiantly around the Canadiens. In fable and in reality, he remains an incandescent figure on and off Montreal ice.

For more, see all 100 Greatest Players