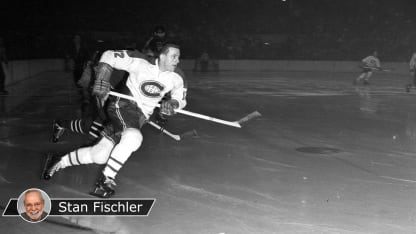

Moore overcame litany of injuries to thrive with Canadiens

Hall of Fame forward was on six Stanley Cup winners, won two scoring titles despite often playing hurt

Take a look at Dickie Moore's career and you'd have to wonder how he managed these feats, and why Moore's accomplishments with his hometown Montreal Canadiens have been largely forgotten.

One reason he's been overlooked is that his linemates for much of his career were fellow Hockey Hall of Famers Maurice and Henri Richard. "The Rocket" is among the most revered players in NHL history, and younger brother Henri, "The Pocket Rocket," played on a League-record 11 Stanley Cup winners.

When I served as the ghostwriter for Maurice's autobiography, he told me straight-out that Moore never got the credit he deserved. "Dickie was a fighter, a real worker, totally fearless and the guy who made our line work," he said

Reared in Montreal's working-class neighborhood of Park Extension along with teammate Doug Harvey and other future NHL players such as Larry Zeidel, Moore was a product of the farm system cultivated by Canadiens general manager Frank Selke.

"Moore was the greatest junior hockey player in Canada in 1951 before we brought him up," Selke said. "We knew that he'd star for us."

That he did, with 33 points in his first 33 NHL games. But Moore found himself surrounded by such popular French-Canadian whiz kids as Jean Beliveau and Bernie (Boom Boom) Geoffrion.

However, Moore clawed his way to the top with less-obvious skills than his stylish teammates. He was the architect of the Rocket's goals, as well as doing the bodychecking and backchecking for Geoffrion. He also did the fighting for Beliveau.

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

This is a modal window.

Beginning of dialog window. Escape will cancel and close the window.

End of dialog window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

Fischler on Dickie Moore's Hall of Fame career

In between those chores he also battled injuries early in his career that stifled his scoring ability and nearly forced him out of the NHL. But patience and fortitude were his major assets when the future looked bleak.

By the 1955-56 season, Moore found his groove and -- not coincidentally -- the Canadiens won their first of an NHL-record five consecutive Stanley Cup championships.

To win his first NHL scoring title in 1957-58, Moore had to dodge a bunch of hockey potholes that would have detoured a lesser player.

He was neck and neck with Henri Richard and New York Rangers forward Andy Bathgate for the NHL scoring lead with three months left in the season when he broke his left wrist. Moore was considered done for the season, but he thought otherwise. "How about putting a cast on my arm?" he suggested to his bosses. "Let me take care of the rest."

Which he did, despite having to play a large portion of the season on right wing, a position unfamiliar to him.

Although his puckhandling abilities were cramped by the bulky plaster cast on his left arm and his wrist shot could never achieve its normal strength, he didn't miss a game and led the League in goals (36) and points (84).

He was even better in 1958-59. Back on left wing and playing without a cast, Moore won his second straight scoring title with 96 points (41 goals, 55 assists), breaking Gordie Howe's 1952-53 NHL record by one point.

"Moore deserved it," famed Montreal sports columnist Red Fisher wrote. "He's the most valuable player on the Canadiens."

Former Canadiens defenseman Ken Reardon once had been regarded as one of the toughest players in the league and later became a top executive with the Canadiens. Reardon rated Moore one of the best NHL players of all time.

"It was hard to say whether Dickie was a better left or right wing," Reardon said, "although he was an all-star left wing for two years."

© Robert Riger/Getty Images

Moore played much bigger than his size (5-foot-11, 170 pounds), a trait he had to develop on the outdoor rinks of Park Extension and then in the junior hockey.

"I remember Dickie in a junior game against Beliveau's Quebec Citadelles," Maurice Richard told me. "He got them good and mad and just about the whole team went after Dickie, but he wasn't in the least bit afraid. He fought everybody and anybody and held his own."

Zeidel, a defenseman known for his toughness, told me Moore's hockey character never changed from his youth.

"Dickie was as tough as they ever came," Zeidel said. "He had to be where we came from. But as rugged as his game, that's how skilled he was. Nothing was going to stop him from reaching the top."

I remember one episode during the 1957-58 season after a particularly rugged game against the Rangers at Madison Square Garden. Sitting next to him in the Montreal the locker room, I watched him peel yards of tape off his battered body. It was obvious he was biting his lip in pain as the last strip of adhesive ripped the hairs from his damaged right hand.

"This wrist got a chipped bone," he noted. "The left one got broken two years ago and still has to be reinforced. Sure my wrist hurts when I shoot, but the only time I'll stop playing is when it breaks off."

Another of Moore's traits was his ability to goad opponents into penalties. Sometimes it worked, and on other occasions there'd be a scrum; or worse. One of Dickie's most persistent (and equally tough) foes was forward Ted Lindsay of the Detroit Red Wings.

Dickie recalled an incident when he was a rookie and the veteran Lindsay attempted to intimidate him.

"I was all over him one night," Moore recalled. "I guess I provoked him to the breaking point. All of a sudden, he wheeled in his tracks, raised his stick and yelled, 'Get off my back, kid, or I'll run you outta the league."

But there a payoff for the wrath he generated, especially against Detroit.

"I loved to beat those Wings more than any other club," Moore said. "They had been so high and mighty for years. It always felt good to whip them. As for the boos, they didn't bother me a bit, as long as I knew I played a good game."

The pressure that accrued as a physical target was as intense as it had been while he pursued his second scoring championship during the homestretch of the 1958-59 season.

"Eventually, the pressure built up on me," he admitted. "In those last weeks, I was looking over my shoulder to see the guys close behind me. I knew I had to keep going for those points. I was glad when it was over and I had won my second scoring race."

Moore never once complained about not getting many accolades for his two straight scoring titles. As long as he and the Canadiens were headed for yet another Stanley Cup, he was content to skate in the shadow of the Richard brothers and Montreal's other stars.

"Sometimes," he allowed, "I felt I'd rather be down about the middle of the scoring list. That way, people wouldn't notice me too much. When I first broke in I used to wonder what it would be like to lead the League.

"Once I learned, it sort of scared me."

That's about the only thing that "frightened" dauntless Dickie. After the Canadiens had won their fifth consecutive Stanley Cup in 1960 he was earning $20,000, including bonuses. It was good pay in the days of the six-team League, and Moore never beefed about the money.

"I'll play until I'm 60 if I'm able," he promised. "You'll never see Dickie Moore retire from hockey because he's rich."

By the early 1960s, his gimpy knees (he twice broke his leg as a baby) had made it impossible for him to maintain his level of excellence. At the conclusion of the 1962-63 season he told Montreal's management that he planned to retire. Ownership understood his decision, as well as his desire to sign a contract with the Toronto Maple Leafs for the 1964-65 season. But his bad knees limited him to 38 games and he retired once more.

However, when the NHL expanded to 12 teams in 1967, Moore signed on with the first-year St. Louis Blues. Playing alongside Harvey, his old Montreal buddy, he helped the Blues to the Stanley Cup Final -- against the Canadiens.

Moore's legs may have been creaky but his heart was as strong as ever. He finished with 14 points (seven goals, seven assists), one short of the NHL lead, in 19 playoff games.

He retired for good in the spring of 1968 with 607 points (261 goals, 346 assists) and 646 penalty minutes in 719 NHL games, as well as 110 points (46 goals, 64 assists) and 132 penalty minutes in 135 playoff games. Despite Moore's litany of injuries, he played on six Stanley Cup-winning teams with the Canadiens, won two NHL scoring championships and was a First-Team All-Star twice.

"Moore is one of those kids making the customers forget Maurice Richard," Jim Vipond, then-sports editor of The Globe and Mail, said after Dickie established his NHL credentials.

Maybe an overstatement, but close enough to make the point: For much of the 1950s, Dickie Moore was the poster boy for hockey heroism.