Strange as it may seem, the NHL All-Star Game as we know it today was born out of a near-tragedy that ultimately morphed into a matchup of hockey's top players.

The event that eventually led to the All-Star Game began with a mistake made on the ice. The episode that became known as "The Shore-Bailey Incident" involved two captivating characters who starred in the NHL during the early 1930s -- Irvine "Ace" Bailey, a forward with the Toronto Maple Leafs, and defenseman Eddie Shore of the Boston Bruins.

NHL All-Star Game evolved from benefit for injured player

Showcase of hockey's top talent aided Bruins forward Bailey in 1934

By

Stan Fischler

Special to NHL.com

Bailey once was described as "quite an aggressive player who never hesitated to exchange bumps with the league's hardbacks." He weighed all of 160 pounds but was totally fearless and led the League in scoring during the 1928-29 season.

By contrast, the bigger, more muscular Shore had emerged as one of the strongest, most fearsome and most proficient players ever to lace up a pair of skates. He was a puck-rushing defenseman and a scoring threat. Shore, a seven-time All-Star and four-time winner of the Hart Trophy as the NHL's MVP, could skate faster than most forwards and hit harder than most defensemen.

"Shore," columnist John Lardner once wrote, "is the only man in hockey generally known to the people who ignore hockey."

Rivals could never ignore Shore, especially on the night of Dec. 12, 1933, when the Maple Leafs and Bruins played at Boston Garden.

The incident began as a case of mistaken identity while the Maple Leafs were killing a pair of overlapping penalties and nursing a lead. Toronto coach Dick Irvin deployed defensemen Red Horner and King Clancy and used Bailey as his lone penalty-killing forward.

After Bailey skimmed the puck into the Bruins' zone, Shore retrieved it and began picking up speed, but Horner tripped him into the boards.

Frank Selke, then Toronto's assistant general manager, said Shore was intent on retribution and charged at a player he thought was Clancy. But that player was actually Bailey, who had dropped back to fill Clancy's vacated position and whose back was turned to Shore.

According to Selke, Shore struck Bailey across the kidneys with his right shoulder. The impact of the blow was so severe that Bailey took a backward summersault, landing on his helmetless head.

"Shore kept right on going to his place at the Boston blue line," Selke wrote. "Bailey was lying on the blue line with his head turned sideways as though his neck were broken. His knees were raised, legs twitching ominously.

"Shore, little realizing how badly Bailey had been hurt, merely smiled. His seeming callousness infuriated Horner, who then hit Shore a punch on the jaw. It was a right uppercut, which stiffened the big defense star like an axed steer.

"As Eddie fell. with his body rigid and straight as a board, Shore's head struck the ice, splitting open."

The Bruins cleared the bench and charged at Horner, but Toronto teammate Charlie Conacher rushed to Horner's side, and the teams eventually went back to tend to their injured players.

Bailey sustained a cerebral concussion with convulsions and appeared incapable of recovery. Before being taken to the hospital, Ace looked up at Selke from the infirmary table and pleaded, "Put me back in the game; they need me."

According to Montreal columnist Elmer Ferguson, "Bailey was as near death as it was usable for any man to be without passing over the borderline."

Few publications recorded Shore's version of the episode. One that did was the April 1956, issue of the now-defunct magazine Blueline, in which author George Girsch quoted Shore:

"I saw Marty Barry [of the Bruins] coming up the ice with the puck, and I raced to get out of the Toronto zone before an offside was called." Shore estimated his speed at 22 miles per hour.

"I had absolutely no premeditation. I had never had any animosity toward Bailey, and there was no malice in my heart. I was partially dazed after colliding with Ace and had no recollection of seeing Horner hit me. All I remember was when I woke up in the dressing room."

In a face-to-face interview with this author, Maple Leafs center Joe Primeau, who witnessed the collisions, offered his version of the incident:

"When Eddie reached our defense, Horner stopped him with what seemed to be a trip, and Shore slid into the end boards.

"Horner recovered the puck and moved up the ice with it. Meanwhile, Ace took up Horner's position. Since Ace was tired, he leaned over to catch his breath. But I'll never know whether Shore mistook Ace for Horner."

The daily clamoring for Shore's scalp abated when Bailey was released from the hospital two weeks later. In his first public statement, Bailey said: "I didn't see Eddie, and he didn't see me when we crashed."

Nevertheless, Shore was suspended and the Bruins sent him on a recuperative vacation. One month later, the NHL concluded that since Shore had never taken a match penalty for injuring an opponent, he would be reinstated. He missed 16 games before returning to the lineup in January 1934, unrestricted in his play.

But in a sense, the furor had not really ended. Although Bailey had escaped death, the head injuries ended his playing career. Knowing that Bailey still had to support his family, the NHL rallied to support him.

On Feb. 14, 1934, the Ace Bailey Benefit Game was played at Maple Leaf Gardens, with the home team playing against a team of All-Stars. One player who expressly asked to play was Shore, whose wish was granted.

More than 14,000 fans packed Maple Leaf Gardens. The audience seemed to collectively hold its breath when Bailey stepped on the ice to present special sweaters bearing his name to all the players. Bailey himself appeared overwhelmed by the Maple Leafs and All-Stars side by side.

"Ace could scarcely see the great men before him," wrote author Ron McAllister, "because of the tears of honest pride that trickled down his face."

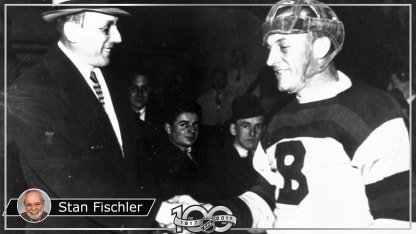

The players skated up to Bailey one by one and shook his hand as the fans roared their appreciation. Whether deliberately or by accident, the announcer did not call Shore's name until the very end. Suddenly the crowd was silent, and a strange aura fell over the building.

Finally, the announcer called out: "Eddie Shore." The silence continued. Veteran reporter Elmer Ferguson, who witnessed the episode, called it "the most completely dramatic event I ever saw in hockey."

Holding his head erect, Shore skated straight for Bailey, stopped a few feet in front of him, and extended his hand. "There must have been hundreds," Ferguson said, "who instantly thought 'Will Bailey shake the hand of the man who almost killed him?'

"That was in my mind as well. It must have been in Shore's mind too. For the sudden hush that fell upon the crowd in dramatic contrast to the bedlam that raged before indicated that here was the moment of climax.

"It was the dramatic culmination of two months of strain, of tension, of columns writing hate, of Shore's suspension from the league action."

Ferguson insisted that Bailey thrust his hand out without hesitation. Hall of Fame broadcaster Foster Hewitt, who also witnessed the confrontation, put it another way:

"They looked at each other for a moment," Hewitt said, "then clasped hands and talked quietly. What thoughts they had or what they said were never announced. But the cordial meeting of the two stirred the crowd into wild bursts of applause."

Bailey's No. 6 was retired by the Maple Leafs that night. He received $20,910 from the benefit All-Star Game, plus an additional $6,764 raised from a benefit game in Boston.

Meanwhile, Shore's appearance in cities throughout the League engendered enthusiasm instead of enmity. He was cheered by 16,000 fans at New York's Madison Square Garden, and he received a similar ovation at Montreal's Forum.

When the Maple Leafs played the Bruins in Boston on March 6, 1934, it was Bailey who dropped the puck. He and Shore then shook hands on a spot just a few feet from where Shore had ended Bailey's playing career three months earlier.

Bailey remained in hockey as a well-respected off-ice official in Toronto. Shore continued playing for Boston until 1940, when he was sold to the New York Americans. He retired after the 1939-40 season and bought the Springfield franchise in the American Hockey League. Shore was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1947, and in 1970 was awarded the Lester Patrick Trophy for outstanding service to hockey in the United States.

Looking back, it's clear that the Ace Bailey All-Star Game proved a success, as did another such benefit game held for the family of Howie Morenz on Nov. 2, 1937; the longtime Montreal Canadiens star died on March 8, 1937, less than six weeks after breaking his leg in a game against the Chicago Black Hawks.

But the official NHL All-Star Game as we now know it did not debut until 1947 when the All-Stars beat the Stanley Cup-champion Maple Leafs, 4-3, before a crowd of 14,169 at Maple Leaf Gardens.

Though the format has changed since that first benefit game following a near-tragedy 83 years ago, the All-Star Game remains an annual showcase of hockey's biggest stars.