RinkWatch is a citizen science research initiative that asks people who love outdoor skating to help environmental scientists monitor winter weather conditions and study the long-term impacts of climate change. Launched by researchers at Wilfrid Laurier University in January 2013, participants from across North America have submitted information about skating conditions on more than 1,400 outdoor rinks and ponds. In addition to contributing valuable data to environmental science, RinkWatch has become an online community for people who love making backyard and community rinks.

In honor of Green Month, the NHL is sharing stories of its environmental efforts to ensure the sport of hockey thrives for future generations.

How climate change is affecting outdoor skating

RinkWatch studies impact on rink building as part of NHL Green Month

© Tom Szczerbowski/Getty Images

By

NHL Green

Every NHL fan knows that outdoor skating is important to the history of the game of hockey. Gordie Howe learned to skate on frozen ponds near Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, while Wayne Gretzky polished the skills that made him The Great One on the backyard rink his dad built for him while he was growing up near Toronto. You don't have to live in a wintery place to become an NHL player -- just ask Toronto Maple Leafs forward Auston Matthews, who grew up in Arizona -- and kids who grow up with outdoor rinks don't automatically become professional hockey players. But as anyone who lives in the northern United States or Canada will tell you, one of the best things about winter is to skate outside with your friends and family on a crisp, cold day.

As the climate changes and the Earth warms, what will happen to backyard rinks and frozen ponds? Have they already started to disappear, like Rocky Mountain glaciers? For the past five winters, we have been collecting information from North American backyard rink makers through a citizen science project called RinkWatch to try and answer these questions. Each winter we ask rink makers to tell us about the conditions for rink building and skating in their neighborhood, and we pool that data to analyze how air temperatures affect rinks.

If you are a regular reader of the NHL Green blog, you will remember

this article from 2015

, in which we described the type of data we collect from RinkWatch. It identifies the best temperatures needed to get a backyard rink going -- a cold snap of 4-5 consecutive days below freezing will suffice if you are using a plastic liner to hold your water. It takes longer if temperatures fluctuate, if your site is not level, or if you don't have a liner. Once a rink is built, temperatures are not the only thing that affect its effectiveness. Precipitation, site conditions, the amount of shade, and the rink maker's experience are also important factors, but we find that when average daily temperatures are colder than 22 degrees Fahrenheit, most rinks will be skateable, regardless of other factors.

By combining RinkWatch data with general circulation models of the Earth's climate, we have

published in a scientific journal

forecasts of how long the outdoor skating season will be in Canadian NHL cities by the end of this century. We found that skating seasons will shrink most in the East, with Montreal and Toronto likely to lose more than one-third of their current outdoor skating days. In Calgary, where winters are typically longer and colder, the skating season will shrink by about 20%.

We also published a study in which we asked RinkWatch participants -- without whom none of this would be possible --

why they build backyard rinks in the first place

. Backyard rinks are an awful lot of work, as anyone who has built one knows, and it can be quite frustrating when Mother Nature refuses to cooperate. Though some parents build rinks so their kids can practice hockey skills in hope of becoming the next Gretzky, most people say their motivation is to create spaces where their kids, the neighbor's kids, parents, grandparents, and friends can play, stay fit, and have fun during the coldest and darkest months. In other words, backyard rinks are community assets, built and maintained by families who care. It would be a shame to lose them to climate change.

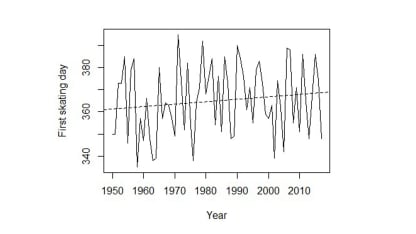

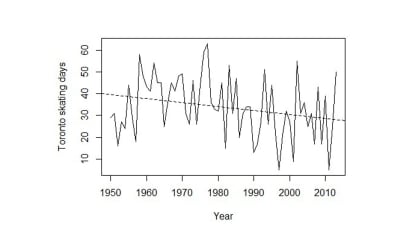

Our latest study has been to reconstruct the length of outdoor skating seasons since the 1950s, when backyard rink building first became popular, from historical weather records. We are starting with the Original Six NHL cities - Boston, Chicago, Detroit, Montreal, New York, Toronto -- each of which has its own history of outdoor skating. We are still finalizing the results, but since April is NHL Green Month, here's a preview for NHL.com readers. We will use Toronto as an example, since it is the closest NHL city to Wilfrid Laurier University, where we are based. On average, Toronto temperatures get cold enough to build an outdoor rink in late December or early January. There is considerable year-to-year variability, but as you can see from the first of the two charts below, the skating season is today more likely to arrive in early January than in late December, making for a slightly later start. More worrisome is the second chart, which shows the number of high-quality skating days per winter has declined by roughly one-quarter, with most of that decline happening since the 1960s. We also observe in the last two decades a growing frequency of bad outdoor skating seasons that have few very cold days. We hate to break this to rink makers in Boston and New York, but our early results for your cities don't look so good, either (we will share the final figures with you in a future posting to NHL.com).

So what does this mean? It means that all of us need to join the NHL and the NHLPA in making environmental and social sustainability a priority. To learn more about what the NHL is doing to reduce its environmental impact and what you can do, please go to NHL.com/green.

Seventeen of the past 18 years on record have been the warmest ever recorded. If this trend continues, there will be many undesirable consequences, many of which will be far more serious than the loss of outdoor skating opportunities. When scientists warn that Earth's climate will warm by 6-8 degrees this century, it's not necessarily easy to visualize what that future will look like. But hockey fans, we can imagine what it means. If we want to avoid a future where kids can no longer skate outside and dream of being the next Howe or Gretzky, the time to start reducing our collective environmental impact is now.

Chart 1: Arrival date of temperatures cold enough to build a rink in Toronto, since 1950

Note: The numbers on the vertical axis refer to the Julian calendar, where December 31st = Day 365 in a non-leap year. Days numbered greater than 365 fall in the following January.

Chart 2: Number of high quality outdoor skating days per winter since 1950

Note: A 'high quality' day is one that is colder than -5.5oC (22oF), meaning that most rinks in the city are skateable.

To learn more about what the NHL is doing to reduce its environmental impact and what you can do, please go to NHL.com/green.