Matheson emphasizes mental side of hockey with Panthers

Defenseman uses psychology background to sharpen focus, mentor other players

The Florida Panthers defenseman was the aggressor in a play that resulted in a concussion for Vancouver Canucks rookie forward Elias Pettersson on Oct. 13. Two days later, he was suspended two games by the NHL Department of Player Safety.

It was his first suspension, but what he'll remember more from the ordeal are the insults and vicious attacks sent his way on social media following the hit on one of NHL's brightest young stars. They were disturbing and could have sent him down a path of self-doubt he'd traveled before.

"It was probably one of the hardest things I've faced as an athlete," Matheson said. "Having so many people call me names and attack me as a person without having ever met me was difficult to cope with. I think it would have affected me a lot more when I was younger."

But it didn't. Matheson has learned too much about the mind, about psychology in sports, to allow outside noise to create an internal struggle in his head the way it used to.

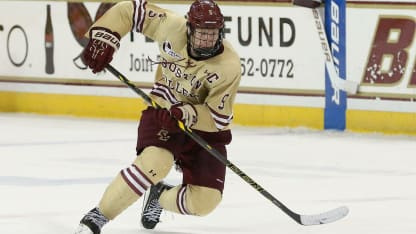

Matheson, who earned a degree in psychology from Boston College after finishing his course credits while riding buses in the American Hockey League, attacks his day job with veracity, so much so that the Panthers' first-round pick (No. 23) in the 2012 NHL Draft has become a consistent presence on Florida's blue line, averaging 21:53 of ice time per game with 15 points (two goals, 13 assists) in 41 games this season.

But the 24-year-old's continued development as an NHL player hasn't stopped him from pursuing his interest in the mind or using himself, a defenseman in the first year of an eight-year contract, as his own test subject.

Matheson makes sports psychology a daily part of his life. He routinely talks with Dr. Derick Anderson, the Panthers' full-time sports psychologist. They talk at the rink after practices and games, and occasionally over the phone.

There is no set schedule, and Matheson doesn't go into Anderson's office, sit on a couch and let out his feelings. They talk about dealing with pressure, how to best approach difficult situations.

Matheson tries to pay it forward by being that outlet, that sounding board and mentor, for players in his former midget AAA program.

He aspires to use his hands-on knowledge of the mind and the pursuit of understanding it through sports psychology in his post-playing days to benefit professional athletes like him who need what can liberally be called a mind coach.

"Hockey players and all athletes spend so much time and effort and money on developing their physical part of the game and then everyone says, 'The game is 70 percent mental, 30 percent physical,'" Matheson said. "Then why are we spending so much time on the 30 percent and nothing on the 70? To be a professional athlete, you have to focus on the physical side and work like crazy to be able to compete, but I like to think a lot of athletes could benefit from focusing on the mental side as well. That's where I always envisioned bringing my degree, working on that 70 percent."

To get his degree and reach this point in his career, Matheson had to clear his own mental hurdles.

Growing up

There were sleepless nights for Matheson before he found his mental equilibrium.

They happened at BC when he was 18, 19 years old and staying up until all hours thinking about mistakes he made during games.

"I'd replay plays over and over and over and over," Matheson said.

As if that wasn't enough, Matheson sometimes also had an important exam the next day. He'd have to park the bad play and refocus. If he didn't, he wouldn't be able to get through the test.

The problem was that it was almost out of character for Matheson at that age to forget about it. He had struggled with it since childhood, his older brother recalled.

"I remember when we were younger," Ken Matheson said, "we'd be playing ball hockey on the street or whatever sports we decided to play that day, football or soccer or anything else, he was always the young guy out there with something to prove and then he'd get angry with not being able to beat any of us. He would hold a grudge on it all the time. He'd be the first one to get angry and have to be sent home, like 'All right Michael, go cool off and come back when you're ready.'"

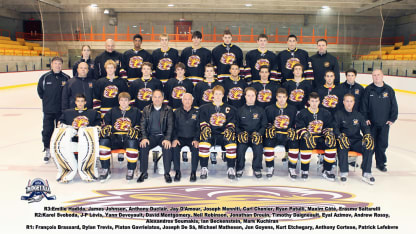

Jon Goyens began the process of coaching Matheson through his mental issues when Matheson played for him with the Lac St-Louis Lions in the League Midget AAA of Quebec at 15 years old.

Goyens quickly recognized Matheson's cerebral nature and the negative effect it was having.

"He was so well-intentioned, wanted to help, wanted to hit a home run every time he was on the ice and that would play against him," Goyens said. "What would happen is he would make one little mistake and now he tried to hit two home runs on the next play. So, he would compound his mistakes and he was super hard on himself because he had high expectations of himself."

The external expectations placed on Matheson at that age made it an even heavier load for him to bear. He was a highly ranked player in Quebec, meaning the expectation was for Matheson, a native of Pointe-Claire, a Montreal suburb, to play in the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League.

Matheson was more intrigued by college hockey. It did not play well in his province.

"There was a lot of heat on him," said Rod Matheson, Mike's father. "A lot of the Quebec media gave him a hard time about it."

Goyens said, "He used to tell me it was a constant barrage from even dads, parents of his teammates as he walked out of the rink. They'd be like, 'Hey, so what are you doing? Where are you going?' He was 15, 16 years old."

Matheson said no to the QMJHL both before and after Shawinigan selected him in the second round of the 2010 draft. He wanted to go to college because he felt an education was important in case he didn't make it to the NHL, or even if he did.

It helped that academia was in his bloodlines.

His parents, Rod and Marg, graduated from Concordia University in Montreal. Ken graduated from Hamilton College in Clinton, New York, and works for Sportlogiq, a sports analytics company. His sister, Kelly, graduated from Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario, and works for Royal Bank of Canada in Toronto. Ken and Kelly were also hockey players.

"Ultimately, your environment is going to influence you somewhat," Rod said. "He knew he had two parents that both went to university, a sister at that time that was in university and a brother that was too."

And at 16, Matheson was telling the world he was leaving for the United States Hockey League and that he would be going to play college hockey. He was ridiculed for taking the nontraditional path.

© Egidio Perugini

"You grow up pretty fast when you are in high school and you jump in the car, turn on the radio and somebody is bashing you about whatever decision you've made," Matheson said. "It makes you grow up pretty quickly, but I was really lucky to have my parents there to guide me through it and help me with that. I'm sure they were able to deflect a lot of things that didn't even really get to me."

Goyens helped too by working on Matheson's mind as much as his physical gifts.

"I would challenge him to express himself as much as possible," Goyens said. "I would challenge him to work on the mental game but in a more basic way."

Goyens did so by reaching back to the teachings of his father, Chrys Goyens, a hockey writer who has authored more than a dozen books, including autobiographies of Jean Beliveau and Larry Robinson.

"My dad was always pushing me to think about why is that working, why is this, why is that," Goyens said. "With Mikey, it was generating this connection of genuine conversations. What's going on? What did you see here?"

The concept was to acknowledge the good or bad, learn from it and move on, Goyens said.

"I don't want to say that I went Sigmund Freud on him or anything like that," he said. "It was just stuff that was super relatable to a 15, 16-year-old."

It was around that time that Matheson started to develop his fascination with the mind and the psychology of sports.

"Jon Goyens was fantastic about it," Rod said. "He knew what buttons to push. He's not the type of guy that stroked his ego, but he just knew where to push him and when to help him."

Goyens made sure Matheson stayed on the right mental path when he was at BC, making it a point to befriend then-Eagles associate coach Greg Brown, who is an assistant with the New York Rangers.

"It was all about how do we get this guy to shake off a mistake, how do we get him to shake off a bad game?" Goyens said. "In pro sports, you play a game, jump on a plane, and do the same thing two days later. You can't be carrying that weight of the world on you because you had one bad period, one bad shift or even one bad game. You need to instill instant amnesia."

Matheson still has those moments, though Panthers coach Bob Boughner said they're less frequent.

"I think it's one thing we worked on last year," Boughner said. "He'd almost be in shutdown mode when he made a mistake and we got on him. We never get on a guy for no reason. We're doing it in a constructive way. But it was tough for him to decipher that last year. He has been better at it this year."

Matheson cited a play in Florida's 5-1 loss to the Pittsburgh Penguins on Tuesday as an example of how he's improved in this area.

"I was skating back for a puck that had been flipped out into the neutral zone," Matheson said. "I took a quick shoulder check and I saw their team change so I tried to turn and pass it up right away, but I didn't see that one of their players stayed on the ice. The puck went right on his stick and he came the other way. Nothing came from it, but in the past that really would have gotten to me."

Goyens wasn't surprised to hear that, especially because he said he could tell Matheson was on the right path late in his rookie season. He had a 15-minute visit with the defenseman after a Panthers morning skate in Montreal on March 30, 2017, and came away impressed and relieved.

"In that conversation, I could tell he wasn't sweating the small stuff," Goyens said.

Goyens said he specifically noticed that Matheson wasn't focusing on coaching decisions and that he was talking about the things he was doing well, not dwelling on the negative. He said he noticed his body language was different, that he had an air of confidence.

"I left that conversation and the first guy I texted or I might have even called was Greg Brown," Goyens said. "I told Greg Brown, 'Mikey gets it.' I told him that the thing we were concerned with, shaking off that bad game, now he has mentally developed an 'I got this' mentality. He needed to develop more of a swagger and he has.

"The Panthers lost that night, but that night he scored in the Bell Centre. Ever since then, he has flourished."

A pseudo-internship

As a pro, Matheson has found a real-life way to learn about sports psychology and enact some of the principles of a sports psychologist.

He does it in his personal life with his fiancee, United States women's national team defenseman Emily Pfalzer, who plays for Buffalo of the National Women's Hockey League. She was a pre-med and biology student who graduated from BC with a degree in biology with an interest in pediatrics.

"We both have pretty stressful environments that we work in, if you want to call it that," Matheson said. "When she was going over to PyeongChang (South Korea) for the Olympics last year, the pressure was at an all-time high and we'd have some conversations about just thinking of how lucky we are to be in the shoes that we are in and realizing that as much as it's U.S. vs. Canada [in the] gold-medal game, pressure is at an all-time high, they haven't won in however many Olympics, it's still just a hockey game."

Matheson also does it at the rink with Anderson, the Panthers psychologist, who he refers to as a mentor, teacher and a friend.

"The one thing I've really taken away from him is he's never trying to get you to talk," Matheson said. "He's always available for you, but he's never trying to get you to talk. He said one of the most difficult things is to do nothing and wait for guys to approach him."

Matheson said they often talk about refocusing his mind, similar to what Goyens and Brown used to do for him.

"Think of three things that when you're playing well are prevalent in your game," Matheson said. "That's just one thing that I know that I talk with him about. It's not about getting caught up in this game didn't go well or I didn't play well the game after that. That's fine. Nobody is going to be perfect.

"I think it's just a great tool to be able to have somebody who isn't your coach, it's not your girlfriend or wife, it's not your parent; it's just someone you can go to to be a sounding board, to vent about something, even if it isn't about hockey. It's important to have that sounding board who can talk you off the ledge so to speak and bring your energy and attention back to what will help you get better instead of continuing to focus on things that will prevent that."

Many of the Panthers players talk to Anderson.

"I've spoken to him on numerous occasions regarding many different things," defenseman Aaron Ekblad said. "You can even go to him for relationship advise. It's as simple as that, and he's going to give you his true, honest opinion, and a lot of times it works."

Where Matheson differs, Anderson said, is in his follow-up questions.

"He likes to pursue information in an effort to gain complete understanding," Anderson said. "He wants to know how the information pertains to him and further how he might best apply the information in a real-world way to his game. I think this comes from his innate interest in how the mind works in general."

Matheson is already putting his interest, and Anderson's teachings, into practice. For the past few seasons, Goyens has been putting some of his former players in touch with his active players and asking them to be mentors.

"Mikey is our poster boy for this," Goyens said.

Matheson was the first former player Goyens sought to be involved in what he calls the Lions' unofficial mentoring program. Matheson said he tries to talk with the players Goyens puts him in touch with exactly how Anderson talks to him.

He gets players' numbers and reaches out to them first via text. He feels if he calls, it puts the players on the spot too quickly. Matheson wants them to feel comfortable. He'll introduce himself, tell them if they ever need anything to call or text, that he'd love to chat if they're interested.

Then he waits.

"I try to leave it up to them to decide how much they want me involved and how much they want to talk to me," Matheson said. "I learned that a lot from Dr. Anderson. He said the hardest thing is to do nothing sometimes. I try to apply that to the guys that I've spoken with. I don't want them to feel like, 'Oh, I have to talk to Mike.' If they want to talk to me then great. If they don't feel like they need it, that's good too because it means they're sure of themselves."

He took that tact five years ago with defenseman Jeremy Davies, who was then a 17-year-old playing for the Lions. Davies was Matheson's first mentee.

They talked in-depth about Davies' life, game, what's ahead and how to best deal with the pressure of it all. Matheson spoke from experience. Davies listened, because he wanted to do what Matheson did: leave Quebec to play in the USHL, setting up a chance to play NCAA hockey.

"I started asking him questions like how is the jump going from midget AAA to the USHL, how did you like the USHL as a league, what are your thoughts on Boston College and the Hockey East," Davies said.

Davies, a 22-year-old junior alternate captain and communications major at Northeastern, was a first-team All-American last season. He is a prospect in the New Jersey Devils system after being selected in the seventh round (No. 192) of the 2016 NHL Draft.

"Mike definitely paved the way and was someone I definitely leaned on throughout the whole process," Davies said.

Their mentor-mentee relationship has blossomed into a full-blown friendship. Davies and Matheson skate together in the summer. They talk at various points throughout their seasons.

"I'm not shy to say it, he's my idol," Davies said. "Even if I'm 22 and he's 24, almost 25, he's my idol. He's someone I look up to and he's someone I'm always going to look up to. I don't think there is any better person or better hockey player that I've met or played with that is better to look up to than Mike. I've been really fortunate to know him and he's helped me a lot."

Just as Matheson continues to benefit from his relationship with Anderson.

"That's really all it is, building a relationship with somebody," Matheson said. "It happens to be that Dr. Anderson is a sports psychologist and has educated himself in a way that allows him to professionally help."

'You have to have some sort of plan'

Matheson and the Panthers haven't had the season they were hoping for, certainly not after the way they finished last season, when a late surge left them one point short of clinching a Stanley Cup Playoff berth on the last day of the regular season.

Florida (17-18-8) is sixth in the Atlantic Division with 42 points entering its game at the Canucks on Sunday (7 p.m. ET; SN, FS-F, NHL.TV). The Panthers are 10 points behind the New York Islanders for the second wild card into the Stanley Cup Playoffs from the Eastern Conference. Matheson is minus-21, the worst rating on Panthers. He has a 49.00 shot-attempts percentage, which entering Saturday ranked 21st on the Panthers, eighth among Florida defensemen and tied for 133rd among NHL defensemen who had played at least 10 games.

Nobody in the Panthers hierarchy seems discouraged.

"He's still a young guy and he's still learning how to manage his game a little bit, but when he's good, he's really good," Boughner said. "That's been the task of this coaching staff, trying to make him a consistent player every night, manage his game. His skating is unbelievable. He has a great shot. He sees the ice well. He gets out of trouble in his own end with his feet. He's got a lot of things that make him a great hockey player. He's still got another level, I think, but we know how good he is because he can affect the whole outcome of a game."

Panthers general manager Dale Tallon thinks so highly of Matheson that he called him "a breath of fresh air."

"He's a world-class kid with a great family," Tallon said. "I think he rubs off on guys. The more players you have like him in your locker room the better it is. When we draft players we always push them to take a course, to keep their mind occupied, to improve themselves. When you get a kid like that who just does it on his own, it's refreshing."

Matheson does it on his own because he wants his future to be as interesting and challenging and rewarding as his present.

"You can't have spent that much time working on your education and not think, 'What am I going to do with it later?'" Rod said. "It's, what, 10-15 years or something that you'll be playing if everything goes right? You could find yourself at 30 going, 'Wow, I've got a long time ahead of me, what am I going to do?' He's thought about that."

That's why Matheson jumped on board two seasons ago after the NHL and NHL Players' Association jointly launched the NHL/NHLPA Core Development Program, which was created to allow players an opportunity to develop a path to success off the ice and deliver a customized strategy to enhance their overall performance during their playing careers.

"You have to have some sort of plan," Matheson said. "You can't blindly go through life just thinking, 'Oh, I'll play hockey forever.' Sports psychology is something that has always interested me and I think there could be a lot of value in it."

The value he's found so far has helped make him a better, more mentally mature defenseman. How Matheson pays that value forward could wind up as his legacy.

"This is no way, shape or form a pumping-of-the-tires type of comment," Goyens said, "but Mikey is definitely the type that where ever he invests his time and effort after hockey, that walk of life will be that much richer than it was before because his care level for other people is super high, super genuine. There is no one who can speak ill of this guy. Even if you're a slightly bad person, this guy has your back."