Stastny asked to speak with Nordiques president Marcel Aubut, who immediately took the call when he was informed that someone named Peter Stastny wanted to speak with him.

Stastny informed Aubut that he and Anton would be willing to sign with the Nordiques in a package deal. Aubut and Gilles Leger, then the Nordiques director of personnel development, were on the next flight to Innsbruck.

The four of them met after tournament games, and covert negotiations took place. When it became apparent that a deal would be reached, Peter sent instructions to his wife, Darina, eight months pregnant at the time, to hurry to join them in Innsbruck.

Following an 11-1 loss to CSKA Moscow in the tournament final, when the players boarded the Slovan team bus, the Stastnys were missing, already in Aubut's rental car on their way to Vienna.

"[Those were] the scariest moments of my life," Stastny told IIHF.com. "It was like being part of a John le Carré novel."

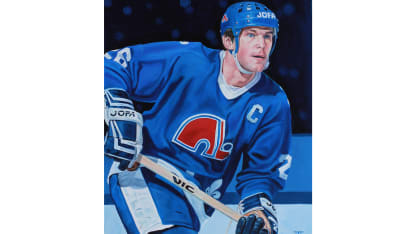

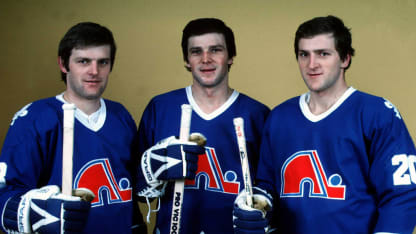

The next day, the Stastnys arrived in Quebec and the shocking news hit the hockey world.

Their older brother, Marian, who was married with three children, stayed behind. But in retaliation for his brothers' defections, Marian was suspended from hockey in his homeland. He defected and join them in Quebec a year later, skating with his brothers on the same forward line. (Each of the three scored in an 8-3 win against the Boston Bruins at Boston Garden on Jan. 5, 1984.)

There were still more repercussions for the family: their father had his job and apartment taken away by the Communist government because of his sons' actions.

Back home, the Stastny brothers became what was known at the time as non-persons, their records expunged, their hockey feats deleted.

"Officially, no one talked about it," Jiri Hrdina, who played in the NHL from 1987-92, said of Peter Stastny, his teammate with Czechoslovakia. "Unofficially, everyone knew him and what he was doing.

"When we'd go to a friendship tour in West Germany, we'd get papers and read about him. Ninety percent of the people had their fingers crossed for him."