TAMPA -- So where do you begin with brothers Phil Esposito and Tony Esposito, the Hockey Hall of Famers who are sitting in a quiet corner of a hotel restaurant, spinning one fabulous yarn after another for 90 minutes?

You could start with the adolescent joyride they took in their hometown of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario; two teenage boys, neither with a driver's license, tooling up and down the main drag in their father's nearly new 1956 Mercury Monarch, cruising for girls with their baby sister, Terry, howling in the back seat because Phil had accidentally safety-pinned her cloth diaper to her skin.

Phil Esposito, Tony Esposito share stories, laughs

Brothers, Hall of Famers discuss memories from childhood, NHL, beyond

Or maybe you begin with what they hung for years on their basement drywall, over a crater that had been put there by one of their hurled bodies during a wrestling match -- a Catholic church calendar they'd pinned on an accidentally holy wall.

Perhaps the starting point is the fire they set in the basement when they tried to sneak a cigarette, only to have a lit match set paint rags ablaze before they took even a puff. Their father scorched himself extinguishing the flames near the furnace whose belly he would shovel full of coal.

Or maybe it's the modern, hilarious horror stories about the taking-forever renovations on their respective homes, with Phil bemoaning late window delivery that has left some of his place shuttered with boards and Tony's home office being expanded so, as Phil jokes, "he'll have more room for all his [stuff] that he's saved up."

As the brothers nostalgically glide from one story to another, riding their hijinks through the decades like rolling waves, you realize that their lives have been more eventful than any of the wildest fiction you could write.

Sixty or so years after their rule-bending fun as kids, Phil, having just turned 75, and Tony, 73 (and 14 months his junior), are laughing like mischievous schoolboys as they fill in the blanks of their stories, finishing each other's sentences, remembering names of those who were swept up in this boyhood madness -- willingly and otherwise.

"Tony," Phil blurts, "why didn't you tell me you're on Facebook?"

"Because I'm not. I don't Facebook," Tony replies, the popular social network a verb in his vocabulary.

"Oh yes you do," Phil says, thumbing at his phone, vowing to find his brother's alleged page. "People are saying all kinds of things and you're liking them."

"I'm not liking anything," Tony says, the phony account later discovered, a no-lifer using the former goalie's name.

I have had occasion to speak many times over the years with Phil and Tony separately, seeking their input for a variety of stories or to chat for no reason at all. But it wasn't until 2017 Honda NHL All-Star Weekend in Los Angeles in late January that I corralled them, shortly before the gala where the second part of the

100 Greatest NHL Players presented by Molson Canadian was unveiled

.

The brothers, each on this elite list, live not far from each other in the Tampa area, though business and leisure travel often has them on the go. They said they would be delighted to sit together for some storytelling in Florida if we could all circle the same date on a calendar -- preferably not a calendar with the face of Jesus covering a hole in a basement wall.

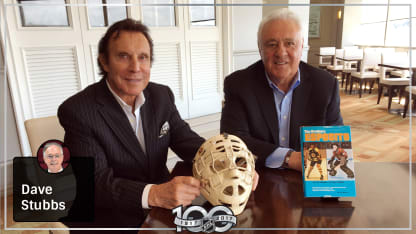

So now, a month later, we're sitting in a Tampa hotel breakfast nook late one morning, the final few diners approaching them almost timidly for a photo and a good word.

Phil arrived 40 minutes behind schedule, having been detained across the street at Amalie Arena; there was a little work to be done for the Tampa Bay Lightning, the NHL team he co-founded and still works for as a radio analyst, seldom letting the inconvenience of the game get in the way of his commentary.

Tony stepped out of his car at the hotel's front door at precisely 10:30 a.m., as planned. He was carrying a paper shopping bag that contained a few photographs of himself and Phil as tykes and grade-schoolers and the fiberglass face mask he had worn for almost his entire 16-season NHL career, modifying it often as he played.

The brilliant brothers were inducted into the Hall of Fame four years apart, Phil first in 1984.

Phil was the gifted sniper of the Boston Bruins, a two-time Stanley Cup winner whose career began with the Chicago Black Hawks (then two words) in 1963-64, took him to Boston in 1967-68 and finally to the New York Rangers for six seasons beginning in November 1975. He won the Art Ross Trophy as the NHL's leading scorer five times and won the Hart Trophy as the League's most valuable player twice.

Tony made his NHL debut with the Montreal Canadiens in 1968-69, then moved on to Chicago in '69 for 15 seasons, winning the Calder Trophy as the NHL's top rookie in 1969-70 and the Vezina Trophy three times.

They were highly competitive growing up in Sault Ste. Marie -- the Soo, as it's known -- but their bond was never broken as they progressed through hockey's developmental leagues.

They would be teammates in bantam, though when Phil went off to Sarnia, Ontario, to play Junior B, Tony quit the game for a year to play some football before returning to hockey with the new Junior A Soo Greyhounds.

In time, their paths would intersect in the NHL. Phil arrived five years before his brother, who had gone to study business at Michigan Tech and play goal for the Huskies, becoming a three-time first-team All-America selection.

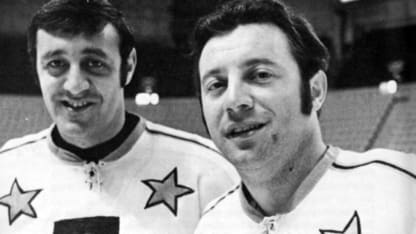

During their illustrious careers, they often faced each other as NHL opponents. Indeed, in Tony's first career start, on Dec. 5, 1968, Phil beat him twice in a 2-2 tie between the Bruins and Canadiens in Boston.

© B Bennett/Getty Images

"Tony's wife, Marilyn, and our mother said the same thing: 'How could you do that to your brother? You're going to ruin his career before it starts,' " Phil says. "I said, 'He played great, he had [35] shots. Somebody had to score. It's part of the game.' "

The next time the brothers met, 16 nights later in Montreal, Tony made 41 saves, stoning Phil several times in a 0-0 tie.

"It was one of those games - so fast, back and forth, wide open," Tony says of the second of his 76 NHL shutouts, with Boston's Gerry Cheevers unbeatable at the other end of the Forum ice.

"You can't get any better than that, you can't write that script," Phil says. "We could have played all night and not scored a goal."

The brothers weave their stories seamlessly from the present to the distant past.

"We used to have fun with the girls," Tony says, turning back his clock to the 1950s. "I remember drawing a bead on the nicest girl in the school and I'd go after her. I was in Grade 6 and she was in Grade 8, a pretty girl, short hair."

And for a moment or two he rattles off the names of most of the girls in his school, the identity, though not the magic, of his Grade 8 crush lost to him.

It seems that all of the pranks the two relate on this morning feature Tony as the innocent wingman or reluctant accomplice. Phil will have none of that.

"Tony just pulled his stuff with none of the women around, in private," he says, laughing.

If the Esposito brothers were destined to make it to the NHL, they say it's in part because of where they grew up. Sault Ste. Marie, on the eastern tip of Lake Superior, nestled between Lake Michigan and Lake Huron, was a small steel town during their 1940s and '50s adolescence, cold enough that Tony remembers it having outdoor ice for five months of the year and good asphalt the other seven for road hockey.

More important, the two boys had each other.

"The great thing about it is, we're so close in age that we were able to do things together," Tony says. "It wasn't like a three- or four-year gap; we had somebody to play with all the time. We'd go down to the one outdoor rink in town, early in the morning or late at night. We'd use a flashlight to light our way."

Phil nods at the memory.

"I remember putting Tony's equipment and mine on a toboggan and dragging it down to what I think now is Esposito Park," he says. "Our old man would say, 'You guys walk, it's good for you.' "

They each speak wistfully of their parents, whom they lost a year apart in the mid-1980s.

Patrick Esposito quit grade school as a teenager to go to work during the Great Depression, the son of an Italian immigrant who arrived in Canada near the turn of the 20th century to work in the Soo's steel mills.

Patrick would become a laborer and a welder and in 1941, the year before Phil was born, he married Frances DiPietro, building the family's first house for $3,000 and paying it off in six years. The blue-collar, no-nonsense patriarch would become a manager for a steel firm, a self-made man having worked his way up from odd jobs. He was fiercely proud of the two sons who skated out of the Soo into the NHL.

The brothers' hearts return to their hometown when Tony slides a couple of childhood photos across to Phil. Within 10 seconds, they are arguing, mildly, about the precise location it was taken.

Tony wins the discussion, and this much is certain: Blessed Sacrament Church is in the background, and Phil remembers being thrown out of its confessional by Monsignor O'Leary.

"He wouldn't let us play hockey," he grouses. "He wouldn't let us do [anything]."

Tony was the good student of the brothers, earning a business degree 50 years ago at Michigan Tech while starring in goal for the Huskies en route to the NHL.

"Phil never much cared for school," Tony says.

"Let's be honest. I got kicked out," comes the reply.

Phil recalls playing Junior B in Sarnia and returning late from a road trip when the team's bus was slowed by a blizzard.

"I had a Grade 12 English exam at my Catholic high school the next day," he begins. "The smart [aleck] that I am, I wrote on it, 'I don't know nothin',' signed my name and went to sleep. Mother Superior brought me into the office and called me a hockey bum. That's when I said, 'I don't like school, I don't want to be in school.' "

Of course, Phil didn't bother to tell his father that he'd dropped out and was enjoying an extravagant life away from his books.

"The old man was sending me $10 a week and I got a job as a janitor, making $50 a week," he says.

"You were living high!" Tony says.

"Absolutely," Phil says. "Ten bucks from the old man, 10 bucks for playing hockey and my janitor's salary -- $70 a week. Man, I was doing great, buying everybody hot hamburgs. Our landlady's son used to make home brew in the basement. We'd steal it and go out in the street and sell it to make a few more dollars, too."

Phil needed neither a mop nor moonshine once he made it to the NHL and started filling nets, nor would Tony need to lean on his diploma after finishing with 15 shutouts in his rookie season in Chicago, no longer part of a platoon in Montreal, where he played 13 games and went 5-4-4 in 1968-69.

They would keep track of each other through the years, combing the summaries for their surname.

"I'd look in the paper when the Black Hawks were playing to see how many shots Tony had, what the score was," Phil says. "I did. I used to do that all the time. The guys on the teams, the Bruins specifically, would drive me crazy when the Black Hawks would come in. They'd say, 'Tony can't do this, he can't see, just throw the puck at him, no problem.' Johnny Bucyk would sit beside me and I'd say to 'Chief,' 'Wouldn't we like to have him?' And he'd say, 'You've got that right.' "

"We were both on pretty good teams," Tony says. "I loved the fact that we both set records. One year (1970-71), Phil had 76 goals and 76 assists. Back in those days, that was unheard of."

"Fifteen shutouts," Phil says with a low whistle of his brother's rookie total, still the highest in a single season for any goaltender since the 1920s.

"As you get older, when you're retired, you see all these records," Tony says. "And as you get older, everybody thinks you're better than you were."

"That's true," Phil chips in, grinning. "Including yourself."

Teammates as boys, they would be on the same team again for the East Division in the 1970 NHL All-Star Game and famously wore the same jersey for Canada in the historic eight-game 1972 Summit Series against the Soviet Union.

But they never played on the same NHL team, though they nearly did for Chicago in the late 1970s. An almost-trade still gnaws at them.

"I was traded to the Black Hawks, for Jimmy Harrison, in 1978 or '79 by (Rangers coach and general manager) Freddie Shero," Phil says. "I was pulled off the bus in Denver by (assistant coach) Mike Nykoluk and told, 'Phil, we've just traded you to Chicago.' I was so excited to be able to finish my career where I'd started and play with Tony for whatever time I had left.

"I was back in the hotel when Nykoluk called and said, 'Sorry, you're playing with us tonight, the trade didn't go through because Harrison couldn't pass the physical.' "

Phil maintains he probably never should have been traded by Chicago a dozen years earlier, not that he fared badly in Boston. He was moved to the Bruins on May 15, 1967, with forwards Ken Hodge and Fred Stanfield for forward Pit Martin, goaltender Jack Norris and defenseman Gilles Marotte.

"I was a rebel. I admit it," he says, shrugging.

"He was a sarcastic son of a [gun]," Tony says with a laugh.

"[Black Hawks coach] Billy Reay would catch me imitating him all the time," Phil says. "But Bobby Hull was the instigator. That [guy] would get me in more trouble than anyone I ever met. But Bobby also taught me more about life and hockey than probably anyone."

In retirement, the brothers found their way into hockey management in the 1980s, Phil as GM and coach of the Rangers, Tony as GM and hockey operations director of the Pittsburgh Penguins.

After being shown the door in New York in 1989, Phil was deep in efforts to bring the Lightning into the NHL in 1992 when he called Tony, who had been fired in Pittsburgh, also in 1989.

© B Bennett/Getty Images

"Pretty simple," Phil says. "I called Tony and told him that I needed him to run hockey operations down here. He just said, 'Sure.' When we got the team, Tony basically ran the hockey and what I did is try to sell tickets."

His brother having taken a phone call, Phil pauses and says quietly, "Mom and Dad would have been so proud of their two sons, working for the same team."

Tony remembers his brother "having no time for the B.S. or the nuts and bolts" of Lightning hockey management.

"I was a detail guy," Tony says, "but we had to have promotion. We realized this; we had to split it up somehow so Phil could sell tickets and I could run the team. You couldn't do both jobs."

It's during our talk that Tony discovers, a quarter-century after the fact, that it was Phil who forever would sneak into his office and raid his office-drawer stash of red licorice.

"Oh, we'd talk about things," Phil says. "Tony would come in and ask me what I thought about this or that. I'd want to be informed, but it was his show."

If Tony chose a third-round 1998 NHL Draft gem in Brad Richards, the Conn Smythe Trophy winner as Stanley Cup Playoff MVP in the Lightning's 2004 championship season, he lost a 1994 battle with Phil over trading defenseman Joe Reekie to the Washington Capitals for Enrico Ciccone, a skating tank cut from the same frayed cloth as "Slap Shot" maniac Ogie Ogilthorpe.

"Reekie was going to help us but Enrico would put people in the building because he was so nuts. When he lost his temper, he was certifiable," Phil says, grinning, of a player who went on to earn 604 penalty minutes in 135 games during five seasons with the Lightning.

"Ciccone was big," Tony says of the defenseman (6-foot-5, 220 pounds). "You couldn't get near him. And mean. Nobody wanted to [mess] with him, anywhere in the League, because everyone knew he was cuckoo."

They laugh today about their cooking skills. Phil is a grill master of sorts, though Tony says he's never flipped a steak or burger, concerned that if he excelled at it, the tongs would be his for life.

"Phil's not a cook, he's a griller," Tony says. "When he comes to our place, he throws steak, Italian sausage and all that junk on the barbecue."

Phil tips his hat to Marilyn Esposito, meanwhile, for her advice on making a sauce "that I doctor up with veal and pork and let simmer for seven or eight hours."

As an ambassador for the Blackhawks, Tony travels regularly to Chicago for appearances on behalf of the team whose logo he wears on his belt buckle. If Phil is doing less than a handful of things at any one time, he's relaxing. (A week after we sat in a Tampa hotel, Phil was getting off a plane from China, where he had been exploring business possibilities, and Tony was in Chicago for a few Blackhawks promotions.)

© Bill Smith/Getty Images

Their brotherly bond is unshakable, no matter the squabbles, the potholes, the heartache and happiness and the challenges in and beyond hockey that they've lived through since they pulled a toboggan to a cold rink in the Soo.

"When you're brothers, there's blood. You're bonded by that, No. 1," Phil says. "And the fact that we both played in the NHL and both got into the Hockey Hall of Fame is something that people dream about, I guess. I never thought that we'd do that, did you, brother?"

"For two brothers to get into the Hall of Fame like we did is great," Tony says. "And the one thing about Phil and I is that we were competitive but we weren't resentful of each other because while we were both successful, we both weren't forwards or centermen or goalies. We didn't really have any competition, so to speak. Sure, I wanted to stop him and he wanted to score …"

"That's part of the deal," Phil cuts in, soon reminiscing about sort-of baseball games they played for hours in the yard as kids, trying to swat plastic cups with a sawed-off broomstick that served as their bat.

"Competitive? Tony is going to deny this, but here's a perfect example. My wife, Bridget, and I go up to his cottage in Wisconsin about four or five years ago and I say, 'Let's go bowling, Bridget and Marilyn want to bowl.' So we all go but Tony says, 'I'm not bowling.' "

By now Phil's laugh is filling the dining room.

"When Tony saw how bad we were, he said, 'OK, I'll bowl the next one.' He just would not do it unless he could be good at it."

Tony sniffs at the story, though he admits he strives to overachieve.

"That's why I could never play golf," he says. "If I wanted to shoot in the 80s, I'd have to play three or four times a week and take lessons.

"Phil and I tried to outdo each other as kids, that much is true," says Tony, who then raises an eyebrow when he notices the gloss of his brother's freshly manicured fingernails.

"They're shiny!" he exclaims, shaking his head. "Phil, if you want to polish something, go wax your car!"

And then he nearly faints when Phil tells him that he's had more than just a manicure; he's had a pedicure as well.