A Seattle expansion team will play in the NHL starting in 2021-22. NHL.com is posting a series of stories this month about the NHL Seattle organization, the local hockey scene and the city's rich hockey history.

Today, why NHL Seattle calls this a return to hockey.

Seattle NHL expansion team latest chapter in city's rich hockey history

Market with 'lots of unique things' welcomes back sport at major league level

SEATTLE -- Major league hockey arrived in Seattle to great fanfare.

"There isn't a doubt in the world but that hockey will make a tremendous hit in Seattle, for anyone who likes to see skill and daring coupled with dazzling speed is sure to take kindly to the game," newspaper columnist E.R. Hughes wrote.

That wasn't written Dec. 4, when the NHL announced Seattle expansion.

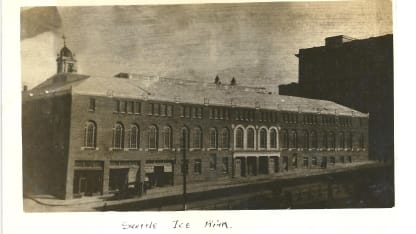

It was written before the Seattle Metropolitans, an expansion team in the Pacific Coast Hockey Association, played their first game at brand-new Seattle Arena on Dec. 7, 1915. Hughes introduced the sport to readers of the Seattle Daily Times.

"No one who has never seen ice hockey can be made to understand what a fast game it is," Hughes wrote. "It is action, action, action all the time …"

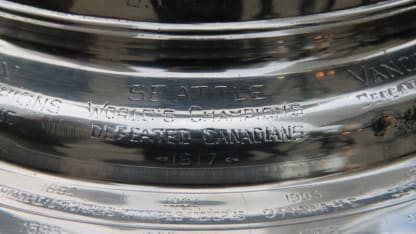

The Metropolitans became the first U.S. team to win the Stanley Cup when they defeated the Montreal Canadiens of the National Hockey Association 3-1 in a best-of-5 series in 1917, months before the NHL was founded. The entire series was in Seattle. Teams didn't travel back and forth then, and the PCHA and NHA, the top leagues at the time, alternated as hosts.

But the Metropolitans are more than the answer to a trivia question, and Seattle's hockey history extends well beyond them. High-level hockey has been played in the Seattle area by various teams in different leagues almost continuously since. A hockey team used the name Seattle Seahawks long before the NFL team did.

The Metropolitans played the Canadiens for the Cup in Seattle again in 1919, with the Canadiens as an NHL team this time, but the series wasn't completed because of a flu epidemic. They played the Ottawa Senators of the NHL for the Cup a year later, losing the series 3-2 on the road.

NHL teams played exhibitions in Seattle at least 12 times from 1922-69.

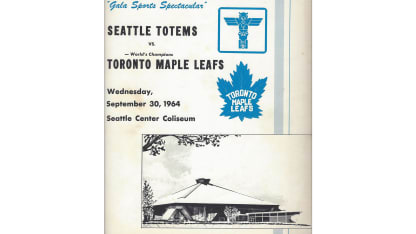

The first sporting event at Seattle Center Coliseum -- which became KeyArena, which is being redeveloped into an $800 million arena for the NHL expansion team -- was an exhibition between the Seattle Totems of the Western Hockey League and the three-time defending Stanley Cup champion Toronto Maple Leafs on Sept. 30, 1964.

George Armstrong, Andy Bathgate, Bob Baun, Johnny Bower, Dave Keon, Frank Mahovlich and Terry Sawchuk played under that iconic roof.

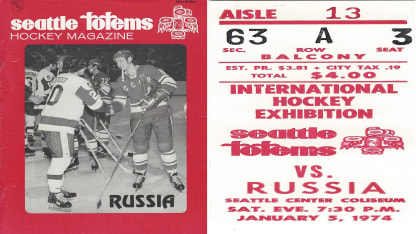

So did most of the team that played Canada in the 1972 Summit Series. The first game between a Soviet Union team and a pro team in the United States was an exhibition with the Totems on Dec. 25, 1972. The Soviets returned for another exhibition Jan. 5, 1974 …

And lost 8-4.

There were extenuating circumstances, but it isn't a stretch to call it a miracle before the "Miracle."

The Totems drew sellout crowds of more than 12,000 to that arena in their best days. Later the Seattle Thunderbirds of the junior WHL did as well. They hosted the Memorial Cup there in 1992.

"This has been a hockey town and will be a hockey town," said Dave Eskenazi, a Pacific Northwest sports aficionado and memorabilia collector.

NHL Seattle has met with Eskenazi, whose collection includes images, scorecards and a pair of forward Cully Wilson's skates from the Metropolitans era. Artifacts could be displayed in a sales center while the arena is being redeveloped and in the arena when it is finished.

In a drawing of the $75 million, three-sheet training center NHL Seattle is building, huge banners hang on the walls of a rink. One has a Metropolitans logo with the date "1917." Another has a picture of a Metropolitans player and the word "TRADITION."

WATCH: [A Home for Hockey in Seattle]

For the expansion announcement in Sea Island, Georgia, NHL Seattle flew out Beverley Parsons, niece of Frank and Lester Patrick, the brothers who founded the PCHA and the Metropolitans. Parsons, 83, wore a Metropolitans scarf to connect to the past, and Jaina Goscinski, 11, wore a Washington Wild youth team jersey to represent the future.

Past meets future. #ReturnToHockey #NHLSeattle

— Seattle Kraken (@SeattleKraken) December 7, 2018

Beverley Parsons is the niece of Frank & Lester Patrick, co-founders of the PCHA & the Stanley Cup winning Seattle Metropolitans. Jaina Goscinski is 11 years old, plays RW for the @WWFHA, and dreams of playing in the Olympics. pic.twitter.com/mVFrCurl3j

At a watch party at Henry's Tavern in Seattle, NHL Seattle handed out buttons and hats with the slogan "RETURN TO HOCKEY." On social media, it uses the hashtag #ReturnToHockey.

"We're still shaking down our brand, but there's lots of unique things here," NHL Seattle CEO Tod Leiweke said. "We should have history and traditions the day we open."

* * * * *

The PCHA was born in 1912 after the Patrick family sold its lumber company in British Columbia and created a league to rival the NHA in the east. Frank and Lester Patrick had played professionally and used their connections to raid the NHA for players.

"The Patricks didn't want to come in and be a minor league," Eskenazi said. "They had designs on being equal or better right from the outset, and just no holds barred in getting that done."

The Metropolitans joined the league after the Metropolitan Building Company built Seattle Arena, also known as Seattle Ice Arena, on the corner of Fifth Avenue and University Street downtown. The brick building was one of the first anywhere with artificial ice, a necessity because of Seattle's climate. Instead of benches, it had what were called "opera-style chairs" at the time. Capacity: about 2,500. Cost: $100,000.

Seattle was booming then, not unlike it is now. The census counted the population as 80,671 in 1900 and then 237,194 a decade later, and by Oct. 15, 1914, U.S. postal authorities counted it as 329,704, according to Seattle, the Queen City, a magazine published in 1915.

The Seattle area hadn't spawned Amazon, Costco and Microsoft yet. But what would become Nordstrom started there in 1901 with a shoe store, and what would become United Parcel Service started there in 1907 as American Messenger Company. Boeing would be born as Pacific Aero Products Co. in 1916.

Alexander Pantages was running a theater empire. He would become a hockey fan.

"It is a bustling West Coast city by 1915 and one desperate to be recognized by the rest of the country," said Kevin Ticen, author of the soon-to-be published book "Immortality: The Forgotten Story of 1916-17 and America's First Stanley Cup Champions." "The Metropolitans were a huge point of pride for helping Seattle feel like a big league city."

Frank Patrick, PCHA president, poached six players from the Toronto Blueshirts of the NHA who had won the Stanley Cup together in 1914: Harry Cameron, Ed Carpenter, Frank Foyston, Hap Holmes, Jack Walker and Wilson.

Cameron went to the Victoria Aristocrats. The others went to the Metropolitans, who also got Bobby Rowe and Bernie Morris from Victoria.

Seattle was stacked. Foyston, Holmes and Walker would end up in the Hockey Hall of Fame. Some argue Morris should be in the Hall. The Metropolitans manager, as the title was then, was Pete Muldoon, who came from the Portland Rosebuds and would become the first coach of the Chicago Black Hawks (then two words) in 1926-27.

"Seattle fans didn't know it at the time, but this was one of the most potent lineups assembled in the early days of the game," Jeff Obermeyer wrote in "Emerald Ice: Hockey in Seattle from 1915 to 1975," one of his three books on Seattle hockey history.

With the Metropolitans wearing maroon, white and green striped sweaters with "S-E-A-T-T-L-E" snaking through an "S," Seattle Mayor Hiram Gill dropped the puck at the inaugural home opener. More than 2,500 saw a 3-2 win against Victoria.

The Metropolitans went 9-9-0 and tied for second in the four-team PCHA. They laid a foundation for 1916-17, when they went 16-8-0 and finished first after a thrilling race with the Vancouver Millionaires. An extra rail car carried Seattle fans to Portland for the critical regular-season finale, a 4-3 Metropolitans win.

When the defending Stanley Cup champion Canadiens trekked to Seattle for what the papers often called the "world series" or "world's series," they left the Cup in Montreal. They had four players who would end up in the Hockey Hall of Fame: Newsy Lalonde, Jack Laviolette, Didier Pitre and Georges Vezina. No team west of Winnipeg or south of the Canadian border had ever won the Cup.

"They didn't bring it," Ticen said, "because they didn't think they were going to lose it."

Royal Brougham, beat writer for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and Metropolitans official scorer, led his preview story like this: "Seattle is hockey wild today."

"Hockey followers from all over the Northwest are flocking to Seattle for tonight's contest," Brougham wrote. "From as far north as Alaska, as far south as Los Angeles and as far east as Nelson, B.C., have reservations been made for seats, and every nook in the University [Street] Arena will be filled."

The Canadiens arrived at 8 a.m. the day of the first game. Face-off was at 8:30 p.m.

"Seattle may win tonight," Canadiens manager George Kennedy said, according to The Seattle Daily Times. "But after that I shall be greatly surprised if my men do not make a clean sweep of the remaining games."

The series went the opposite way.

It was Montreal that won that night 8-4, despite the long journey and the rules. The teams had eight or nine players, and they played odd-numbered games by PCHA rules (seven men per side and forward passes allowed in the neutral zone, most notably) and even-numbered games by NHA rules (six men per side and no forward passes). A headline in the Post-Intelligencer: "Seattle Is Beaten By French Wizards in Opening Battle."

It was Seattle that made a clean sweep of the remaining games, winning 6-1, 4-1 and 9-1, twice defeating the Canadiens under NHA rules. Morris scored 14 goals in the series, Foyston seven. Headlines in the Post-Intelligencer: "Seattle Boys Skate Rings Around Rival Team and Win Title … Metropolitans are Now the Holders of the Famous Stanley Cup."

Brougham quoted Kennedy as saying, "We were beaten by the better team."

"Historians who write of the rise and fall of Les Canadiens dynasty will record how this dashing band of Flying Frenchmen traveled 3,000 miles to find an adversary worthy of its steel and discovered a foe that outclassed it in every department of the great ice game," The Seattle Daily Times wrote.

Well, in hindsight, the Montreal dynasty hadn't even risen yet. The Canadiens went on to win 23 of their 24 championships after that, and they own far more than any other team. But three months after the Metropolitans victory, with a $500 bond guaranteeing its safe return, the Stanley Cup arrived in Seattle.

How amazin' were these Mets? One of their substitutes was forward Jim Riley, would play seven seasons in Seattle and then nine games in the NHL -- six for the Detroit Cougars and three for the Black Hawks in 1926-27. He also was a baseball infielder who would play four games for the St. Louis Browns in 1921 and two for the Washington Senators in 1923. No one else has played in both the NHL and MLB.

"There should be statues of those guys at the new arena," Ticen said. "That's how special they were."

No other U.S. team would win the Cup until 1928, when the New York Rangers won it with Lester Patrick as their coach and general manager. Seattle would not win another major championship until 1979, when the Seattle SuperSonics won the NBA title.

Brougham went on to a legendary 68-year career at the Post-Intelligencer. The street between CenturyLink Field, home of the NFL's Seattle Seahawks, and Safeco Field, home of MLB's Seattle Mariners, is South Royal Brougham Way.

Though the lower bands of Stanley Cup are replaced as they fill up with names, the Metropolitans have a permanent place on the neck, and the Canadiens suffer an infinite indignity.

"SEATTLE WORLD'S CHAMPIONS," the engraving says. "DEFEATED CANADIANS 1917."

The Metropolitans arguably should have won the Stanley Cup once or twice more.

Morris did not play against the Canadiens in the 1919 series because he was arrested for military draft evasion, and his scoring touch was missed. Seattle had a 2-1 series lead and a chance to clinch in the fourth game. Wilson put the puck past Vezina at the end of the first period, but the goal judge ruled time had expired. After four scoreless periods, the game ended in a 0-0 tie because it was played under NHL rules, which allowed for one overtime.

Montreal won the fifth game 4-3 in overtime, tying the series 2-2-1 and setting up a decisive sixth game …

Which never took place.

The series was halted because of the flu epidemic, which infected players on both teams. Canadiens defenseman Joe Hall died in Seattle on April 5.

Morris was acquitted of his charges before the 1920 series and rejoined the Metropolitans, but he wasn't in game shape and came off the bench as a substitute.

The weather was warm and the ice poor in Ottawa, which did not have artificial ice, and the Metropolitans fell behind in the series 2-1. The series shifted to Toronto, which did have artificial ice, and the Metropolitans tied the series 2-2 and took a 1-0 lead in the fifth game. But Ottawa roared back and won 6-1.

The Metropolitans would never come so close again. They folded in 1924, and Seattle Arena was converted into a parking garage. The PCHA merged with the Western Canadian Hockey League, and that league folded in 1926, the year the Stanley Cup became the NHL's championship trophy.

The Seattle Arena building was demolished in 1963 and replaced by an office tower. A plaque marks the site's significance as the "HOME OF THE 1917 STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS."

"Hallowed ground," Eskenazi said.

* * * * *

A new rink was built in 1927 at the corner of Fourth Avenue and Mercer Street at a cost of $1.115 million. It would be known by many names, such as Civic Arena and Mercer Street Arena. It held about 4,500 for hockey and was home to many teams in many leagues for 67 years.

The Seattle Eskimos played in the Pacific Coast Hockey League from 1928-31. The Seattle Seahawks played from 1933-40. They were in the North West Hockey League from 1933-36, then the NWHL changed its name to the PCHL.

Defenseman John Houbregs, who played for the Eskimos and Seahawks, was the father of Bob Houbregs, who was general manager of the SuperSonics from 1970-73 and inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1987.

The Seahawks became the Olympics in 1940-41. The Seattle Ironmen played in the PCHL from 1944-52. In 1952, they changed their name to the Bombers, and the PCHL changed its name to the WHL. The Bombers became the Americans in 1955 and the Totems in 1958.

The Totems won the WHL championship in 1959, 1967 and 1968, led by perhaps the greatest minor league player of all time, Guyle Fielder.

Though he had no points in nine NHL games -- three with the Chicago Blackhawks in 1950-51, six with the Red Wings in 1957-58 -- Fielder had 1,422 points (323 goals, 1,099 assists) in 1,036 games for Seattle from 1953-69 amid a 23-season professional career.

He led the WHL in assists 13 times and in points nine times, and was WHL most valuable player six times, in Seattle. This was at a time when the NHL had six teams, and the rest of the best players were in the WHL and the American Hockey League.

"He was here for a long time," Obermeyer said, drawing out the word "long." "He was a fixture. Every year, no matter how much you turned over the team, Guyle Fielder was still playing center, and he was still going to lead the league in assists. Almost every year that he played, he led the league in assists. It was insane."

The Totems expressed interest in joining the NHL as far back as 1958-59.

President Marvin Burke wrote a piece in the game-night programs declaring "the definite goal of big league hockey for Seattle within the next few years" and the need for an all-purpose arena.

Seattle Center Coliseum was built for the 1962 World's Fair. When it opened for sports in 1964, it had a capacity of 12,700 for hockey.

The Totems lost that inaugural game to the Maple Leafs 7-1 before a crowd of 8,601. But it was a festive event. As if it were a wedding or gala, invitations were sent to this "Extraordinary Exhibition of Professional Hockey." There was a black-tie seating section and postgame reception. The menu included champagne, imported cheese and "Hot-Boeuf Dans Sauce Ala Maple Leaf." Toronto coach Punch Imlach wore a tuxedo behind the bench, complete with top hat and tails.

"The thing that impressed me [was], they made such a big deal out of it," said Bill Knight, who covered the Totems for the Post-Intelligencer from 1962-63 into the 1970s. "I went out and rented a tuxedo, which was the first and last time I ever did that to go to a hockey game."

The Totems averaged more than 7,000 fans their first season at the Coliseum, far more than they had at the old, smaller rink. As the years went on, they would draw well for big games, especially against the rival Portland Buckaroos.

"That was a hell of a facility," Knight said. "They had some good crowds for that time in Seattle sports. They had a great following. It was an 'in' game. Sometimes tickets were not always that accessible."

The Totems drew 12,367 the first time the Soviet Union visited, even though it was Christmas. The Soviets had piqued the public's interest with their performance in the Summit Series, and this was their first stop on a tour of the United States. They won 9-4 without playing starting goalie Vladislav Tretiak.

When they came back little more than a year later, the Soviets were making their last stop on a tour of the United States. They started Tretiak this time but rested four of their top skaters, including Alexander Maltsev and Alexander Yakushev. Before a crowd of 12,710, the Totems took a 5-2 lead into the second intermission.

"The Russian coaching staff was incensed," Obermeyer wrote in "Emerald Ice." "They were on the verge of being embarrassed by a minor league team, and that would not be tolerated. The four players who had been scratched were suited up and sent out to play the third in a desperate attempt to get fresh legs on the ice."

It wasn't enough. And not only did the Soviets lose 8-4 to a minor league team, they lost to a minor league team finished fifth in the six-team WHL with a 32-42-4 record and missed the playoffs for the fourth straight season.

"The big part of the story to me is just how much passion there was with that core fan base all the way through the '50s, the '60s, the '70s," said Obermeyer, who runs seattlehockey.net. "When I talk to those old-time fans, when I go buy their collections and programs and stuff, people were passionate about this team. They had a boosters club that would have a huge banquet dinner every year. The players all went, and it was a formal huge banquet hall affair."

On June 12, 1974, the NHL awarded Seattle an expansion team to begin play in 1976-77. But with Denver also receiving an NHL expansion team and Phoenix moving to the World Hockey Association, the WHL was left with three teams and folded.

The Totems had two seasons to prepare for the NHL but no league in which to play in the meantime. They spent 1974-75 in the Central Hockey League struggling on the ice and at the gate. To make a long, complicated, contentious story short, they folded, the NHL pulled the expansion team, and pro hockey left Seattle. The Totems sued, and after a lengthy court battle, the NHL won.

Major junior arrived in 1977 when the Kamloops Chiefs of the Western Canada Hockey League moved to Seattle and became the Breakers. The WCHL became the junior WHL in 1978; the Breakers became the Thunderbirds in 1985. The team played some games at the Coliseum and often sold out big ones.

After another Seattle group did not close a deal for an NHL expansion team in 1990, the Coliseum was redeveloped in 1994-95 with sightlines more suited for basketball and became known as KeyArena. The SuperSonics left for Oklahoma City and became the Thunder in 2008. The next year, the Thunderbirds moved to a new 6,150-seat arena now known as accesso ShoWare Center in Kent, about 20 miles south of the city.

Now KeyArena is being redeveloped a second time. It will be a new arena again, state-of-the-art again, with 17,400 seats for hockey, and yet will return to its roots, with the same iconic roof and sightlines for both hockey and basketball. Seattle will have a major league hockey back, and this ownership group wants to bring the NBA back too.

Seattle is booming again, a city of more than 3.8 million people and counting, with natives who remember hockey and transplants who brought their love of it from elsewhere.

"The fan base is here," Obermeyer said. "They've been just kind of bubbling under because we haven't had an NHL team here. We haven't had a minor league team here since the Totems in '75. And with the tech boom, there's a lot of people who have moved into Seattle in the last five, 10, 15 years. There's a lot of people that are going to be ready to go to these games."

NHL Seattle wants them to return to hockey. The next chapter is beginning.

"Seattle getting an expansion team as opposed to an existing team, to me and I think to a lot of people here, is important," Obermeyer said. "Clearly this is a better option for us. We're going to have our history. We're starting it on Day One."

Images courtesy of Kevin Ticen, Dave Eskenazi and the Hockey Hall of Fame.