In NHL.com's Q&A feature called "Sitting Down with …" we talk to key figures in the game, gaining insight into their lives on and off the ice.

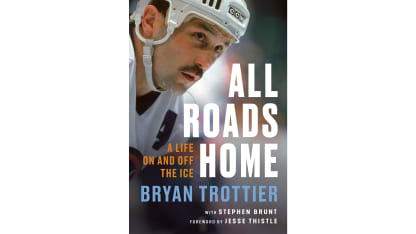

This edition features Bryan Trottier, a Hockey Hall of Fame forward whose book, "All Roads Home, A Life on and off the Ice," was released in October.

Trottier talks opening up to write autobiography in Q&A with NHL.com

Hall of Fame forward discusses playing, coaching career, being diagnosed with clinical depression

© Patrick Smith/3ICE/Getty Images

The timing was right for Bryan Trottier to no longer be guarded.

His book, "All Roads Home, A Life on and off the Ice," shares what Trottier calls "a lot of fun stuff that's not just about hockey." There are anecdotes from growing up on a farm in Val Marie, Saskatchewan, and bonds forged through friendship, family and music. There are stories tied in with Trottier's Metis Cree heritage, cited in the forward written by Jesse Thistle, author and assistant professor in the Department of Humanities at York University in Toronto.

"He stands as the most decorated Indigenous athlete of all time in all of professional sports ... it's because he is humble," Thistle writes. "As you read this book, remember this concept of humility; this is the mark of at true warrior for his people."

Trottier's reasoning for writing the book was simple: He's a lot more open at age 66. Putting thoughts on paper felt a bit cathartic.

"People ask me what I'm thinking, I tell them, where before I would say I can't quite tell you everything," Trottier said. "There's some talking about teammates and talk about family. Yes, mom and dad are gone. To be able to share that side of me about them, about my hometown, there's lots of wonderful memories. There is some of that cathartic feeling, but not a lot. It wasn't the main reason but there's some in it. When you can talk about your memories and achievements or the people that helped you along the way, you're saying thank you in a wonderful way."

Trottier's hockey story has been told and retold: Six-time Stanley Cup champion (four straight with the New York Islanders from 1980-83 and two in a row with the Pittsburgh Penguins in 1991 and '92) and a seventh title as Colorado Avalanche assistant coach in 2001. Winner of the Calder, Art Ross, Hart and Conn Smythe Trophy. A 1997 Hockey Hall of Fame inductee, his first year of eligibility. Teammate of legends Mike Bossy, Clark Gillies, Denis Potvin, Billy Smith, Mario Lemieux and Jaromir Jagr.

His beginnings were humble while living and learning to skate in Val Marie, population 164. The upbringing helped him to never allow success to get in his head.

"Mom and Dad were Ground Zero for me," Trottier said. "There's just always something bringing you back to your roots. All roads home. That's why the title's there."

In an interview with NHL.com, Trottier discussed the book, growing up Indigenous, overcoming clinical depression, his brief tenure as coach of the New York Rangers and more.

Do you ever think about where you'd end up in life without hockey if Dave "Tiger" Williams didn't talk you out of quitting in December of 1972? He drove to your home through a blizzard, arrived at 7 a.m., and told you to get in the car and go back to Swift Current.

"Destiny is a funny thing. In one sense, you have to take advantage of it, but I think for everyone, I think it's a different path. This was mine and to tell the story and share the stories for people to understand, it really makes me feel good because the reviews and people that I've talked to who read the book. I'm really enjoying that. They get maybe another look at who I am as a person, not just a hockey player."

Your father, Buzz, once told you, "When you stop wanting, you die." You then thought, "I'd better want to keep wanting … or I'll die." How do you find that balance between avoiding complacency and obsession?

"You just don't take things for granted. That stops you from being either. You appreciate what you have around you. You take advantage of opportunities, and you keep your focus, recognize things for what they are. Some of this was good fortune. Some of it was a lot of hard work and I'm going stick to the hard work aspect of it because luck isn't going to shine on me all the time. But when good fortune does, you jump into it and grab a hold of that. When you get drafted, you don't take that for granted. So even though it's an obsession to a degree, you're on a mission. You never lose your focus on what the important things are."

You shared how 28 years ago you were diagnosed with clinical depression. How thankful are you that you got help even when you thought asking for it seemed silly?

"Absolutely. It was wonderful, and I thank them tenfold. I always say to myself, if you don't have that kind of, I guess, support, people who care about you, you can fall deeper into the pit. I got a great diagnosis. I got great support. That's just what friends and family do, so it was kind of a reawakening of something you already knew."

You're usually associated with the Islanders, but you won the Cup twice with the Penguins and ended your sixth season as a champion sliding on a wet tarp at Three Rivers Stadium holding the trophy. How satisfying was it to win the Cup again in the late stage of your playing career?

"It was nice ride. Everything has been a nice ride. When I look over my shoulder and I reminisce and my memories cloud my vision, I'm overflowed by emotion, some days, of the path I've taken. It's been special for so many reasons. When I look at my career, and you say, 'Oh, seven Stanley Cups.' Well, seven Stanley Cups in 18 years of playing and then 10 more years of coaching, you lose a lot more than you win. But the winning is so satisfying. The winning is over the top and it just drowns out all those losing years."

You wrote about your love of coaching. Any regrets about not getting at least one full season as Rangers coach or a second chance to do it in the NHL?

"I did for a while. It's kind of like leaving the game. It was just kind of like, hopeful, hopeful, hopeful and then, nah, you know what? I'm really enjoying this this time of my life. I've kind of let go and I recognize too I didn't quite have the demeanor to be a head coach. And that's why I went back with (Buffalo Sabres coach Ted Nolan in 2014-15) because I knew I'd be a really good assistant coach and he was fantastic. That year with Teddy was magical in a whole bunch of senses because it reinforced the fact that I didn't want to be a head coach. I wanted to be an assistant. He reinforced my decision not to be chasing the head coaching job anymore. I didn't want to put the hours and the time in, and I didn't quite have the right … I call it demeanor because to go face-to-face with the media and try not to tell them everything that you're thinking and try to be nice and respectful and all that stuff, it wasn't my personality. I was way too guarded. As an assistant, I get to concentrate on the players. I didn't have to do all the other stuff. Looking back, I think I found my path. I found my joy. For a while I stayed hopeful. But I wasn't heartbroken, so to speak."

You admired Bossy for being good selfish. Are there enough good selfish players today?

"Oh, yeah. It's abundant. Today's game, (Connor) McDavid, (Sidney) Crosby and (Patrick) Kane and (Jonathan) Toews, this generation, they're all about that good selfish. They want to win, but they know that it's about contributing to the win, whether it's scoring goals, blocking a shot or doing what you have to do. Those things pay off. I'm pretty proud of the game. I'm pretty proud of the next generation. I think we're in good hands."