The union members jumped at the idea. But Smythe had less than half a year for Maple Leaf Gardens to be ready for the home opener. Teamwork among the various workers came to the fore as they raced against a tough timetable. Laboring sometimes in three eight-hour shifts, the builders employed 540 kegs of nails, 950,000 board feet of lumber, 750,000 bricks, 77,500 bags of cement and assorted other equipment. Remarkably, the job was done just in time.

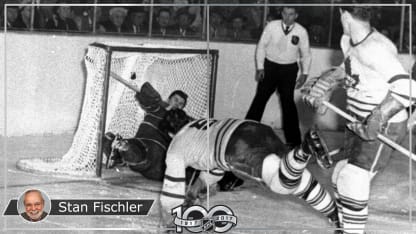

On Nov. 12, 1931, the Chicago Black Hawks (then two words) were scheduled to play Smythe's team, and Maple Leaf Gardens was ready to welcome its first fans.

Every one of the 12,473 seats was filled, and there were about 1,000 fans who had bought standing-room tickets. Those who looked up were awed and did double-takes.

Near the top of the rink, Hewitt was perched in an odd-looking gondola built on steel beams 54 feet above ice level. Thus the introduction to every Saturday night hockey broadcast was, "And now, up to the gondola and Foster Hewitt!"

From his perch high above the ice, Hewitt looked down on a rink glittering with cleanliness and class. Fans were adorned in the same finery they ordinarily would wear to the opera or theater. Many men wore top hats and tuxedos. Smoking was forbidden and a deluxe aura oozed out every corner of the building. The only thing missing on opening night was a victory; Chicago defeated Toronto 2-1.

However, less than five months later Smythe's team put its own, personal stamp of approval and greatness on the new arena. On April 9, 1932, the Maple Leafs defeated the Rangers 6-4 to sweep the best-of-5 Stanley Cup Final in three games and win the franchise's first championship.

Or as Smythe said five months earlier about completion of his Gardens: right on time!