Hall merely was maintaining a heroic tradition of goaltending dating back to hockey's earliest days. One of the first of the outstanding goalies to succumb to injuries and exhaustion was Clint Benedict.

Benedict broke in as a pro with the Ottawa Senators of the National Hockey Association during the 1912-13 season. Watching him in action, you could understand why puck-stopping was, and still is, considered the toughest job in sports.

"After the first couple of seasons," Benedict said, "I lost count of the stitches they put in my head. They didn't have a goalie crease in those days and the forwards would come roaring right in and bang you as hard as they could. If they knocked you down you were supposed to get back on your feet before you could stop the puck. Those were the rules."

Benedict absorbed terrifying punishment for eighteen seasons, with the Senators and Montreal Maroons. "I remember at least four times being carried into the dressing room all stitched up and then going back in to play," he said.

Benedict was ranked alongside Georges Vezina, George Hainsworth as a superior goaltender in the early days of the NHL, and won the Stanley Cup four times (1920, 1921, 1923, 1926).

One of his noteworthy contributions to the art of goaltending was his innovative decision to fall on the ice to block a shot. Until Benedict came along, it was traditional for goaltenders to remain upright throughout the game.

"It actually was against the rules to fall to the ice," he said. "But if you made it look like an accident you could get away without penalty. I got pretty good at it and soon all the goalies were doing the same thing. I guess you could say we all got pretty good at it about 1914, and the next season the league had to change the rule."

Benedict's revolutionary maneuver was greeted with the same hostility as Jacques Plante's decision to wander out of his net when he played for the Canadiens in the 1950s. When he hit the ice the fans shouted, "Bring your bed, Benny!"

More beleaguered a goalie than Benedict happened to be was the Toronto Maple Leafs' Frank McCool, whose career encompassed two seasons and one Stanley Cup.

McCool helped the Maple Leafs win the Stanley Cup in 1945 but he was gone from the NHL almost as quick as he arrived. His problems were rooted in perennial stomach aches brought on by stress.

"I quit early, mainly because of ulcers," McCool said. "Why I had ulcers I don't know, but it didn't help being a goalie. It's the toughest, most underappreciated job in sports.

"The goalie always takes the rap. It's always his fault when you lose. The crowd gets on you and then the papers pick it up. Soon the players themselves begin to think you're to blame."

McCool eventually left hockey to become a journalist. By 1954 he had become the sports editor of the Calgary Albertan, which seemed to justify his decision to quit goaltending at a relatively early age.

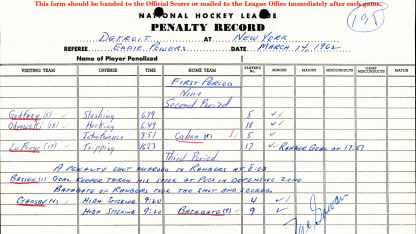

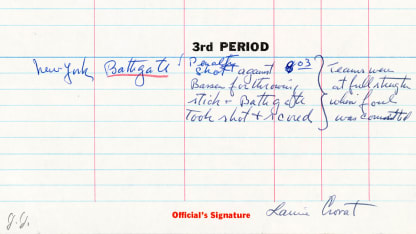

One of the most unfortunate episodes that convinced a goalie that fate -- or referees -- was against him involved the Detroit Red Wings' Hank Bassen during a game against the

New York Rangers on March 14, 1962.

The winner would make the playoffs and the loser would be heading for the golf links. With the score tied 2-2 in the third period, Bassen rushed out of his net and slid his stick along the ice to stop the Rangers' Dean Prentice, who crashed into the boards.

A penalty shot was called, and the referee designated Rangers right wing Andy Bathgate as the man to take the shot. Bathgate was a much more prolific scorer than Prentice. Entering the game he led the League with 79 points and was tied for sixth with 25 goals. Prentice had 54 points (20 goals, 34 assists) to that point in the season.