The voice belonged to otherwise reserved Maple Leafs fan/gas station owner John Arnott, who would urge his team's heart-and-soul player to do what he did best -- provide the spark that would ignite another Toronto victory.

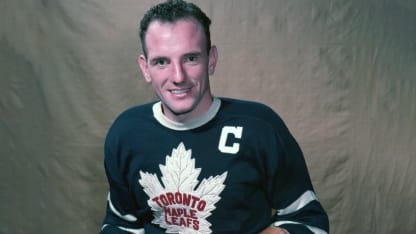

Ted Kennedy traced his nickname, "Teeder," back to the kids who mispronounced "Theodore" in his hometown of Humberstone, Ontario. Whatever you wanted to call him, Kennedy was Toronto's fire-starter, the catalyst for the first Maple Leafs dynasty when they won three Stanley Cup championships in a row from 1947-49 and five between 1945 and 1951. He captained the final two title teams, but even before that Kennedy was Toronto's leader by example. His reputation as a big-time playoff scorer and his ability to score clutch goals, set up others, anticipate the play, dominate in the faceoff circle and forecheck relentlessly all emanated from an intense and unsurpassed desire to win.

"He was not the most gifted athlete the way some players were, but he accomplished more than most of them by never playing a shift where he did not give everything he had," Maple Leafs owner Conn Smythe said. "He was the greatest competitor in hockey."

TED KENNEDY CAREER TOTALS | View Full Stats

Games: 696 | Goals: 231 | Assists: 329 | Points: 560

Ruggedly built at 5-foot-11, 175 pounds, and with energy to burn, Kennedy was enormously popular among fans, who could plainly see the determination etched on his face. "No player worked as hard as he did or showed so many signs of struggle," author Jack Batten wrote in his book "The Leafs in Autumn." "Toward the end of every season, Kennedy would look like a man in torment. From the Gardens seats, his face seemed to swell into small lumps of pain, as if a bunch of golf balls had somehow materialized under his skin. His head glistened in sweat, and when you looked at his hair, kinky with tight little curls, you figured he might have stepped out of a heavy shower. His play was a form of torture."

Some speculated the rationale behind Kennedy's over-the-top work ethic was to compensate for his subpar skating ability. "He was not an easy skater, appearing to run, not glide, on the blades, often with a look on his face as if he were in pain, perspiring from the effort," Frank Orr wrote in the Toronto Star.