Legendary hockey reporter and analyst Stan Fischler will write a weekly scrapbook for NHL.com this season. Fischler, known as "The Hockey Maven," will share his knowledge, brand of humor and insight with readers each Wednesday.

Marchand, Lindsay play same game, says Fischler

Hockey Maven compares greats from past to brightest stars of today

By

Stan Fischler

Special to NHL.com

Watching Calder Trophy winner Mathew Barzal during his remarkable rookie season in 2017-18 was a pleasure that left me wondering.

Time and again, the 20-year-old center for the New York Islanders would execute a move that instantly reminded me of a star from the NHL's distant past. One night the answer finally came to me in a flash -- sort of like Barzal's moves on the ice -- so I turned to my press box pal, Allan Kreda of The New York Times, and blurted:

"You're looking at the reincarnation of

Max Bentley

."

Of course, Kreda being too young to have seen Bentley -- a Hockey Hall of Famer who played for the Chicago Black Hawks, Toronto Maple Leafs and, for one final season, the New York Rangers -- he had no idea where I was going.

"Nobody from the 1940s and 1950s could skate like Max," I said. "That's why someone once said, 'That guy moves like a scared jackrabbit.'"

It's also why Bentley was nicknamed "The Dipsy Doodle Dandy from Delisle" while helping Toronto win the Stanley Cup in 1948, 1949 and 1951.

Barzal has the same kind of electrifying, now-you-see-him-now-you-don't moves that made Bentley such a fan favorite in his era. If there's a difference, it's that Bentley owned a better wrist shot. He claimed he got it milking cows on the family farm in Saskatchewan.

I guess that by now you understand how and why I've been inspired to create a regular "Then And Now" segment, which will run on a monthly basis. Here's this month's edition:

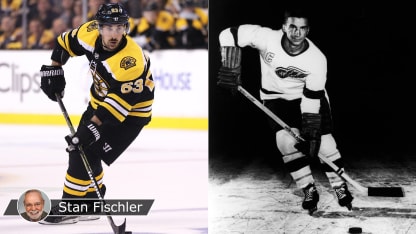

1. Brad Marchand = Ted Lindsay

Tough. Troublesome. Terrific. Any or all those adjectives fits each of them.

Lindsay is a Hockey Hall of Famer who excelled as the left wing on the Detroit Red Wings' "Production Line." Gordie Howe played on the right side while Sid Abel (and later Alex Delvecchio) manned the middle.

Like Marchand, Lindsay was one of the smaller players in the NHL (5-foot-8, 163 pounds) but backed away from no one, no matter how big. He was a leader and a four-time Stanley Cup winner. He also showed his leadership skills off the ice by helping to form the first players' association. "Terrible Ted" is still active at age 93 and remains an inspiration to players of all generations.

Marchand (5-9, 181) is the pepper pot's pepper pot. He helped drive the Boston Bruins to the Stanley Cup in 2011 and is an inspiration to smaller players who hope to make it in the NHL.

Marchand, a left wing, frequently plays on a line with center Patrice Bergeron and right wing David Pastrnak. That unit, like Lindsay's "Production Line," consistently has been one of the best in the NHL. Marchand has maintained top-level play since entering the NHL during the 2009-10 season while never losing the combative spirit that makes a comparison to Lindsay inevitable.

Truculence has been part of the woof and warp of their respective styles.

Lindsay retired after 17 NHL seasons (14 with Detroit, three with Chicago) as the all-time leader with 1,808 penalty minutes, but he could score as well. He finished with 379 goals and was an NHL First-Team All-Star eight times.

Marchand, 30, was a First-Team All-Star in 2016-17 and remains at the top of his game after nine NHL seasons. He's played 602 games and has 459 points (226 goals, 233 assists) along with 578 penalty minutes.

Few players had a nickname that fit them as well as Cournoyer, aka "The Roadrunner," who spent 16 seasons with the Montreal Canadiens. The adage that you can't hit what you can't catch could have been said with Cournoyer in mind. His combination of speed, an IQ (intensity quotient) that was among the highest in hockey and a deadly accurate shot turned him into a no-brainer Hockey Hall of Famer.

For much of his NHL career, Cournoyer teamed with Henri Richard at a time when Francophones dominated Montreal's roster. In addition to Cournoyer and Richard, there were French-Canadian stars such as Jean Beliveau and Serge Savard, as well as role players like Bobby Rousseau and Claude Provost along with goaltenders Charlie Hodge, Gump Worsley and Rogie Vachon.

Cournoyer played on 10 Stanley Cup championship teams, the first in 1965 and the last in 1979. He retired after the Canadiens won the Cup for the fourth straight season. He won the Conn Smythe Trophy as playoff MVP in 1973, setting an NHL record by scoring 15 goals to help the Canadiens win another title.

Hall is coming off a season when he won the Hart Trophy as most valuable player and he's become the face of the New Jersey Devils. Like Cournoyer in his prime, Hall often seems to be racing for loose pucks like a ferret who's got the scent of his prey. His leadership qualities are nonpareil, and his shot has the kind of accuracy that made Cournoyer a threat to opposing goaltenders every time he stepped on the ice.

Hall, 26, has the potential to continue growing as a player; in a sense, the sky's the limit as he continues to hone his game. I can't think of two players more alike in style and substance than Cournoyer and Hall.

The Edmonton Oilers selected Hall with the No. 1 pick in the 2010 NHL Draft, and he spent six seasons in Edmonton without making a trip to the Stanley Cup Playoffs. The Devils acquired him in a trade June 29, 2016, and after one season getting acclimated to his new surroundings, Hall finished with 93 points (39 goals, 54 assists) to help New Jersey make the playoffs for the first time since 2012.

On almost every Hall shift, I'm reminded of "The Roadrunner."

3. Zdeno Chara = Eddie Shore

Shore was one of the biggest and strongest players during the 1920s and 1930s, as well as one of the best defenseman in the NHL with the Bruins.

Eight decades later, the same can be said of Chara.

The only difference was actual size and style of play. Shore (5-11, 190), played like a bull in a china shop during a time that featured more frontier-style rugged action than the speed-oriented game of today. Yet Shore, like Chara, could adapt to any style of play. He was famous for his end-to-end rushes and playing upwards of 50 minutes in a 60-minute game.

The comparison snugly matches when it comes to physical play. Shore's thunderous body checks put fear in the hearts of oncoming forwards. When opponents tried to retaliate with hard hits, he merely brushed them off as part of the game.

In Glenn Liebman's book, "Hockey Shorts," he quoted Shore as saying, "It was pretty much a 50-50 proposition. You socked the other guy and the other guy socked you back."

Fast forward about 80 years and Chara's game has been a virtual replica of Shore's, particularly when it comes to the joy of flattening an opponent. At 41, Chara (6-9, 250) remains as indefatigable as Shore, who played big-league hockey until age 37.

Shore was a mainstay on two Stanley Cup-winning teams in Boston. Chara was captain when the Bruins won the Cup in 2011. He played 73 regular-season games in 2017-18 while nurturing his 20-year-old partner, rookie Charlie McAvoy.

"The tallest player in NHL history knows few ceilings in his quest for personal growth," wrote Fluto Shinzawa, then with the Boston Globe. "A formerly awkward behemoth has shaped himself into his generation's premier shutdown defenseman."

4. Seth Jones = Doug Harvey

Harvey was one of those players who made hockey look simple. He was so calmly sure of himself that he executed plays of extreme complication with consummate ease. But because Harvey lacked the flamboyance of Shore or other Hall of Fame defensemen, he was slow to receive the acclaim he deserved.

"Often, Harvey's cool was mistaken for disinterest," author Josh Greenfeld wrote. "Actually, it was the result of an always calculating concentration."

But Harvey's excellence had become apparent by the mid-1950s.

"Doug Harvey was the greatest defenseman who ever played hockey -- bar none," said his coach, Toe Blake. "Usually a defenseman specializes in one thing and builds a reputation on that, but Doug could do everything well."

Harvey was a superb rusher but lacked the blazing shot that characterized Bobby Orr and never had more than nine goals or 50 points in a season. There is little doubt that Orr, a six-time 100-point scorer, had the advantage offensively, but not as much as the numbers would suggest.

"Harvey," wrote Greenfeld, "could inaugurate a play from farther back and carry it farther than any other defenseman."

Harvey was a consummate craftsman, perhaps unmatched among defensemen for his combination of style, wisdom, and strength. He won the Norris Trophy as best defenseman seven times and was a 10-time First-Team All-Star.

Blake coached Harvey in Montreal in the late 1950s, when the Canadiens won the Stanley Cup for five successive seasons. Harvey was the quarterback of Montreal's historically lethal power play, which also included Bernie "Boom-Boom" Geoffrion, Beliveau, Maurice "Rocket" Richard and Dickie Moore. The Harvey-led power play was so proficient that the NHL changed its rules in 1956 to mandate that when a team scored during a two-minute power play, the penalized player was allowed to return rather than having to sit out the full penalty.

"No player put my heart in my mouth as often as Doug," Blake said. "But I learned to swallow in silence. His style was casual, but it worked. He made few mistakes and, 99 percent of the time, correctly anticipated the play or pass."

Blake added the definitive estimate of the most imposing NHL defenseman since Shore: "Doug played defense in a rocking chair."

I began watching Harvey when he was still playing with the Montreal Royals in the Quebec Senior Hockey League and saw him play throughout an NHL career that began in 1947 and didn't end until 1969. I can see a comparison with Jones.

I started watching Jones in person during the 2012-13 season, when he played for Portland of the Western Hockey League. Ben, my oldest son, lives in Portland and my buddy Travis Green was coaching the team.

Seth Jones takes the No. 32 spot on the list

"Jones is a natural," Green told me. "He got a lot of that from his father (former NBA star Popeye Jones). He's got an NHL future."

What's so amazing is that Jones played one year of major junior hockey before he was taken by the Nashville Predators with the No. 4 pick in the 2013 NHL Draft. He went right from Portland to a regular spot in Nashville, playing 77 of 82 games.

The similarity between Jones and Harvey quickly became evident to me, especially after Jones was traded to the Columbus Blue Jackets on Jan. 6, 2016.

In his three seasons with the Blue Jackets, Jones (6-4, 210) has displayed the same cool, calm, collected game that made Harvey so special.

Like Harvey, Jones has developed an offensive bent. It was evident during the 2017-18 season when he had 57 points (16 goals, 41 assists) and a plus-10 rating. All were NHL career highs.

Blake would have loved this guy side-by-side with Harvey. What a combo that would have been!