Laura Halldorson couldn’t believe what was happening. Nine seconds into the third period of the 2004 NCAA championship game, her University of Minnesota women’s hockey team had taken the lead on Harvard, with a rebound goal by Natalie Darwitz off a pass from Krissy Wendell.

But the officials were gathering. Harvard forward Angela Ruggiero was talking to them, discussing whether a whistle had blown, whether the goal would count.

“I’m worked up, I’m like, ‘That’s our goal, that’s our championship goal. Do not take that away from us,’” said Halldorson, then the Minnesota coach. “I was intense.”

Wendell approached her.

“I’ll never forget, Krissy said, ‘Coach, it’s OK. Because if they don’t count it, we’ll just get another one,’” Halldorson said.

The delay was long, but the goal was good. And 32 seconds later, Minnesota would score again, a Kelly Stephens goal off a Wendell shot. Add in another Wendell goal, a Darwitz goal for a hat trick, and Minnesota had the 6-2 win and the championship.

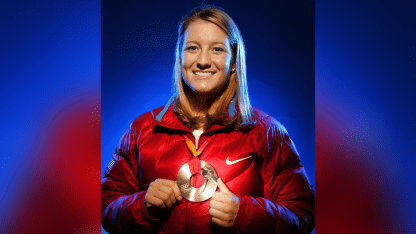

It was classic Wendell.

“She just was so calm and confident and comfortable under pressure in big situations and that’s part of her competitiveness that I always loved,” Halldorson said of the forward.