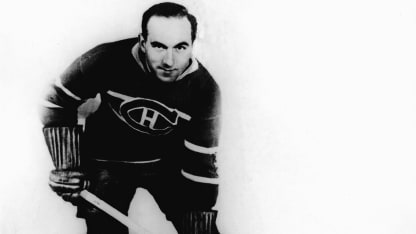

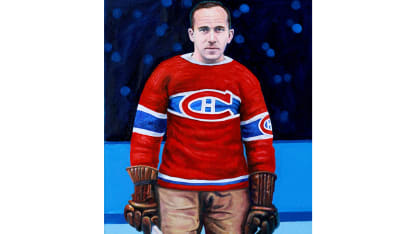

Morenz took over as the first-line center in his rookie season, scoring 13 goals in 24 games to help the Canadiens win the Stanley Cup, and more than doubled his total, to 28, in 1924-25. In 1927-28, Morenz led the League with 33 goals, 18 assists and 51 points, capturing the first of his three Hart trophies, teaming with wings Aurel Joliat (28 goals) and Art Gagne (20 goals) to form the most explosive attack in the annals of the young League. Literally and figuratively, Howie Morenz, No. 7, was in the middle of it all.

"He's not No. 7 to me," Roy Worters, goalie for the New York Americans, said in an article in Sport magazine. "He's number 77777. Just a blur."

Morenz wasn't French-Canadian by birth, and spoke no French, but it didn't prevent him from becoming a Canadian hockey icon, star of three Stanley Cup winners, a 1945 Hall of Fame inductee and a player who earned the admiration of his fiercest competitors, such as Eddie Shore, the bruising, hard-skating defenseman for the Boston Bruins who regarded Morenz as the only player in the League who could outskate him.

"[Morenz] had a heart that was unsurpassed in athletic history, and no one ever came close to him in the color department," Shore said, according to greatesthockeylegends.com. "After you watched Howie you wanted to see him often, and as much as I liked to play hockey, I often thought I would have counted it a full evening had I been able to sit in the stands and watch the Morenz maneuvers. Such an inclination never occurred to me about other stars."

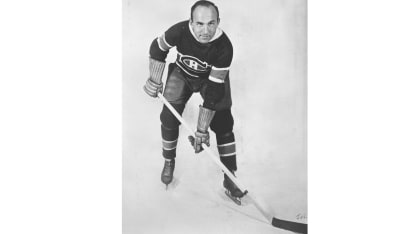

By age 30, Morenz's scoring output fell to 14 goals, and the Canadiens tumbled below .500. He slowed noticeably again in the 1933-34 season, managing eight goals, and Dandurand decided it was time to rebuild, shipping Morenz to the Chicago Black Hawks on Oct. 3, 1934. Chicago traded him to the New York Rangers in the middle of the 1935-36 season. It looked as though the great Howie Morenz would be finishing his career with the Rangers, until new ownership took charge of the Canadiens, a once-mighty franchise that had fallen to last place. With fans discontented and the Forum awash in empty seats, the new owners knew they needed to inject life into their team. They made a deal with the Rangers on Sept. 1, 1936, to bring Morenz back to where his career started.

At 34, Morenz was well past his high-speed prime, but he was nonetheless energized by his return to Montreal, and so were the Canadiens, who were 17-9-3 with a road victory against the Maple Leafs in late January 1937.