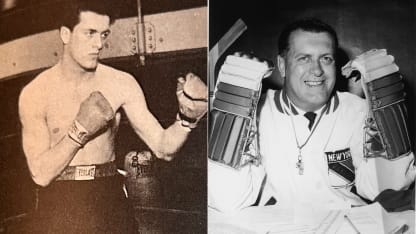

Boxing was still on Patrick’s mind, but hockey began winning the tug-of-war.

"My mother didn't want me to be a fighter," Patrick explained. "I also was concerned about not breathing properly because of a deviated septum. I had an operation and that ended my boxing career.

"That' when I got serious about hockey."

The transition was easy. Having moved to New York in 1934, Patrick hooked on with the Rangers’ minor league team, the New York Crescents, who became the New York Rovers the following season. Since they played their home games at Madison Square Garden, Lester was able to regularly scout his younger son.

"Although Muzz was big, tough and a natural defender, he took his time getting to the NHL,” Goren said. “First it was the Rovers, then the Philadelphia Ramblers, New York's top farm club, and then a one-game NHL audition with the Rangers in 1937-38. His dad was impressed."

Lester promoted Muzz to the Rangers in the fall of 1938. Now he was a teammate with older brother Lynn, who would become one of the League's leading scorers. Muzz, at 6-foot-2, 220 pounds, skated side by side with Hall of Famer Art Coulter. Together, they were an intimidating duo.

Although a boxing career was in Patrick’s rearview mirror, he did throw punches with any on the ice with any opponent willing to go toe to toe with him. His most notorious fight erupted during the Stanley Cup Playoffs in 1938-39 against the Boston Bruins.

"Eddie Shore of the Bruins was considered the No. 1 tough guy in hockey," said Goren who then wrote hockey for the New York Sun. "As a rule, opponents didn't want to mess with him. But when Muzz realized that teammate Phil Watson was in trouble, Patrick was there to help.

"All of a sudden, Shore meddled and that's when Muzz stepped in to protect Phil. He hit Shore with three jolting punches and that was it for Eddie. The blows came so fast and furiously, it seemed that Patrick just tossed one punch."

New York Times columnist John Kieran offered this account: "Muzz was having a fine time and would have lingered longer over Shore except that the referee and gendarmes interfered.

"By that time Eddie looked as though he had gone through a threshing machine on his hands and knees. It took a good half hour to paste and patch Shore together again."

According to Shore biographer, C. Michael Hiam, "Muzz had the upper hand throughout and had broken the Bruin's nose in two places, cut him under the right eye and lacerated his mouth."

Boston won the series and the Stanley Cup that spring but a year later Patrick and the Rangers captured Lord Stanley's chalice in a six-game Final against the Toronto Maple Leafs. Now, the big, cheerful curly-haired defenseman was getting ready for even bloodier fights in the years ahead.

After World War II began in 1939, Patrick became the first well-known NHL player to volunteer for the U.S. Army. He rose from buck private in 1941 to captain at the conflict's conclusion on V-J Day in August 1945.

He participated in the United States invasion of North Africa, followed by the fierce battle at Anzio in Italy. Patrick's last intense involvement was with the GI's invasion of Southern France, which eventually led to V-E Day signaling Germany's defeat in Europe.

After returning to the Rangers and playing 24 games in 1945-46, Patrick turned to coaching and managing. He finished his hockey career in New York, after being named general manager of the Rangers in 1955.

"Muzz turned a lackluster team into winners, reviving a club that had been out of the playoffs for five years," New York Journal-American hockey writer Stan Saplin said.

After nine years of managing, in Patrick moved on from the NHL in 1964. He eventually retired to his home in Riverside, Connecticut, where he died of a heart attack in July of 1998.

But the Patrick love of hockey was passed on through Muzz's family. His son Dick has been the longtime president of the Washington Capitals and grandson Chris is Washington’s associate general manager.

As for Lester, he must have been delighted that his two-fisted son eschewed a career in the ring for life in hockey arenas, especially New York's Madison Square Garden, where ‘The Silver Fox’ held forth for more than two decades.

"Muzz may have been a fight champ," concluded Goren, "but hockey, not boxing, was his first love. It also was his last love -- all with the Rangers. He helped them win a Stanley Cup, then coached and finally managed his beloved ‘Blueshirts.’ A nice hat trick if ever there was one!"