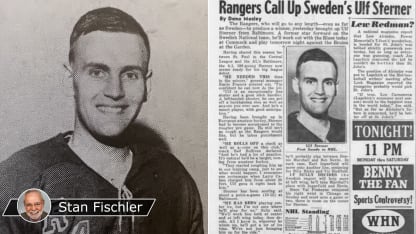

Legendary hockey reporter Stan Fischler writes a weekly scrapbook for NHL.com. Fischler, known as "The Hockey Maven," shares his humor and wit with readers each Wednesday. This week Fischler recalls a landmark game that helped open the NHL to European-trained hockey players.

The event took place 58 years ago this month in New York City -- January 27, 1965, to be exact. Ulf Sterner donned a New York Rangers sweater and skated on to Madison Square Garden ice. The big, smooth-skating forward thus became the first European-trained player in the NHL. Significantly, Sterner's arrival eventually would pave the way for a legion of stars arriving from the continent -- right up to the present.

Ulf Sterner became 1st NHL player from Europe in 1965

Forward born in Sweden played 4 games with Rangers, paved way for others in future decades

By

Stan Fischler

Special to NHL.com

As hockey pioneers go, Ulf Sterner gets less attention than many outstanding players from Sweden who followed him to the NHL. But it's worth acknowledging his courageous breakthrough.

The native of Deje, Sweden already was hailed as a hockey hero in his homeland even before he played in the NHL. During the 1962 World Championship, he scored two goals in an unexpected 5-3 win against Canada. Hockey historian Andrew Podnieks rated it a meaningful international event.

"It was the first time his country had ever beaten the great power and only the third gold medal for the Swedes ever," wrote Podnieks in his book, "Players."

After turning pro, Sterner became a star with Frolunda from the 1961-64. Former Rangers center Ulf Nilsson, who later would play on a line with Sterner during the 1973 World Championship, said it was inevitable that an NHL team would notice Sterner.

"Ulf was one of the best forwards ever to come out of Sweden," Nilsson said. "He was unusual in those days because he was big (6-foot-2, 187 pounds) and good on his skates for a player of his size. In those days, big guys didn't move that fast."

Since I covered the Rangers for The Hockey News in the 1960's, I learned that the team's management had Sterner on its radar and invited him to New York's training camp in 1963.

"But he declined to play that season because he wanted to preserve his amateur status for the 1964 [Innsbruck] Olympics," said Rangers historian George Grimm, author of "We Did Everything But Win." "Sweden won a silver medal and Ulf led all scorers with seven goals and five assists."

The Rangers got back to him and in 1964 he showed up again at training camp. There were, however, misgivings about Sterner's ability to make the NHL grade because of the differing NHL and European styles.

"In Sweden," Grimm pointed out, "offensive zone checking was prohibited. It appeared that Ulf would have trouble with the more rugged game here."

Sterner passed his auditions with New York's minor league affiliates in St. Paul and Baltimore, having no issues with the North American style of play to start the 1964-65 season.

"I talked to (St.Paul coach) Fred Shero about Sterner and he said that Ulf was one of the most talented players that he had ever seen," Nilsson said.

Then came January 27, 1965, when the Rangers hosted the Boston Bruins.

"The Rangers, who will go to any length -- even as far as Sweden -- to produce a winner, brought up Ulf Sterner from Baltimore," wrote Dana Mozley in the New York Daily News.

I recall the excitement at the New York City arena that day, especially among the Rangers staff. Coach Red Sullivan was hopeful when he spoke with the media.

"Sterner will get a lot of ice time," Sullivan vowed. "We're not just bringing him up for the ride. Ulf rolls off a check as well as anyone on this level. They started roughing him up in our training camp just to see what would happen. In one scrimmage, (defenseman) Larry Cahan charged him from about 20 feet. Ulf gave it right back to him."

Sterner's NHL debut was a success. New York defeated Boston 5-2 and although Sterner didn't score, he got good reviews from management, the media: and even himself.

"I am happy, very happy," said Sterner in the post-game scrum with reporters. Then, a pause: "But, I know I have a lot to learn. Much."

Writing for Newsday, Dick Sorkin commented, "He missed what would have been a (future Hall of Famer) Henri Richard-type goal. Sterner carried the puck out of the corner of the Bruins zone, hip-faked his way past two Bruins and backhanded a shot while falling."

"He played a fine game," Sullivan said. "Ulf belongs. After this performance I have no intention of sending him down."

But it was evident that Sterner had some rugged NHL opponents on his mind.

"I don't think many players tried to hurt me," he explained. "None but (Boston forward) Reg Fleming. I don't know if I can be a rough player. I can take it, but all my life I've played in such a way that I mustn't bodycheck too much. Now I have to learn differently."

As it happened, Sterner was scoreless in four games with the Rangers and was returned to Baltimore, where he finished the season. And that was that. He

returned to Sweden and resumed a dazzling career there the following season.

"It must have been really hard for him to be on his own in a new country with a new style of play," Nilsson said. "It was easier for Anders Hedberg and me coming to (WHA) Winnipeg as teammates back in 1974 and eventually to the Rangers."

His NHL career was not a long one. But it was significant.

"Sterner was unwilling to play the more physical brand of NHL hockey," wrote Mike Commito in his book, "Hockey 365." "But his experience demonstrated what other European-trained players needed to do if they wanted to break into the NHL."