Legendary hockey reporter Stan Fischler writes a weekly scrapbook for NHL.com. Fischler, known as "The Hockey Maven," shares his humor and insight with readers each Wednesday.

This week Stan has another episode of his "Voices from the Past." The subject is Hockey Hall of Fame referee Bill Chadwick, who officiated some 900 regular-season games and a then-record 42 games in the Stanley Cup Final during 16 NHL seasons. The New York native is credited with being the first referee to introduce hand signals to identify penalties, a standard practice today. Stan interviewed Bill numerous times from 1954 through the referee's retirement and then during Chadwick's 14 seasons (1967-81) as a radio and TV broadcaster for New York Rangers games, earning the nickname "The Big Whistle."

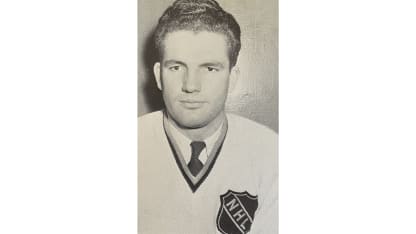

Voices from the Past: Bill Chadwick

New York native overcame eye injury to become Hall of Fame referee, well-known broadcaster

How did you get into hockey while growing up in New York?

"My father bought me a pair of long racing skates when I was 10, and he'd take me to Central Park in Manhattan when the lake froze over. Otherwise, I' d skate at the Ice Palace in Brooklyn, where they allowed speed skates. When I entered Jamaica High School, I learned that it had a hockey team and I showed up for a tryout. I borrowed a pair of hockey skates and made the team. We went on to win the high school championship, and that got me doing some serious thinking about hockey as a future in my life."

How serious?

"I was so enthused about hockey I used to play for a couple of other teams while still skating for Jamaica High. One of them was the Jamaica Hawks, who played in the Met League at Madison Square Garden on Sunday afternoons. On top of that I got on to the Fordham University team, but I had to do some name-changing to pull it off. I played for the Hawks under the name of O'Donoghue, and with Fordham my name was Flanagan. After high school, I got a job on Wall Street where the bankers had a team, the Exchange Brokers. I played for the Brokers under my real name. The Met League games proved a good experience for me because many of the players were much older and more experienced. I got good at it and eventually I had my heart set on actually making it to the NHL."

What stopped you?

"At the age of 19, in March 1935, I was riding high. I was on the Met League All-Star Team playing a club from Boston at Madison Square Garden. It was warmup time when I stepped on the ice when suddenly a Boston player shot the puck and it hit me in the right eye. I was rushed to a hospital, and after two weeks doctors decided there was no way to restore the sight in that eye. Instead of quitting, I went right back to playing hockey in the fall. Even with one good eye, I still could make the same judgements I made with two good eyes. The proof was my getting a place on the New York Rovers, which was a Rangers farm team. Players were going from the Rovers right up to the NHL."

How good were you then?

"Good enough to play center for the Rovers in 1936 and be invited back for the next season. I still had my heart set on a pro hockey career and was playing in the Eastern Amateur Hockey League in another Rovers game. Before I even realized what was happening, I got hit in the left eye -- my good eye -- by either a puck or stick; I'll never know which. What I did know was that blood started trickling into my injured eye and soon my vision was gone. For a while I had no vision whatsoever but, fortunately, the left eye cleared up and I was able to see out of the eye again. Still, I decided I had enough and quit as a player."

How did you manage to stay in the game?

"Tommy Lockhart, who ran the Rovers and the Eastern League and the Amateur Hockey Association of the United States, knew about me. One Sunday, I was at the Garden before a Rovers game when Lockhart's ref couldn't make it. Tom said, "Bill, will you fill in?" Tommy liked what I did, so he asked me to be a regular ref in the Met League and a linesman in the Eastern League. Soon, Lockhart moved me up to EAHL referee and I had my real baptism of fire. I had become a full-fledged official, but it also almost cost me my career."

What went wrong?

"I was assigned to do an Eastern League game in River Vale, New Jersey, not far from New York. The River Vale Skeeters were owned by a fellow named John Handwerg and coached by an ex-NHL player, Art Chapman. They obviously didn't like the game I was calling and both of them kept giving me the business over the three periods of play. I was so angry after the game that I contacted Lockhart and told him straight out, 'I'm finished. I'm never going to referee again.' But Tommy calmed me down and insisted that things would get better."

How did you get into the NHL?

"I had 'quit' on a Saturday night, and four days later I got a wire from NHL President Frank Calder. He said he was appointing me as an NHL linesman. Calder said I'd start off by being linesman at all Americans home games at the Garden. I was a kid of 22 and the next thing I knew, I was doing a game between the Amerks and Canadiens, My referee was Bill Stewart, who also had been a National League baseball umpire. In those days the NHL used one referee and one linesman. Canadiens (general) manager Cecil Hart was giving us a hard time throughout the game. As soon as the game ended, Stewart said, "Follow me!" So, I followed him and he walked right into the Montreal dressing room to challenge Hart. I knew then that that was what refereeing was all about. Of course, nothing came of it. Hart just brushed him off because Stewart was a hothead who felt nobody could criticize what he was doing. All I know is that in 1941 I was appointed a regular referee in the NHL.

Who among the owners knew you only had one good eye?

"Everybody on the Board of Governors knew it, but nobody ever said anything about it. Everything moved smoothly until I had to report to the draft board after the United States entered World War II. I asked for a two-week deferment so that I could handle the playoffs before joining the Army. Somehow the story leaked and a Detroit paper ran a headline 'One-Eyed Referee Asks for Draft Deferment.' Somehow, nobody else picked up the story -- not even the New York papers -- and, as it turned out, I wasn't drafted because of my bad eye. But I did have problems with Detroit after that. It never was a good idea to cross the Red Wings because that club had a lot of influence. Between (general manager) Jack Adams and the owner, James Norris, Detroit had a lot of clout. I managed to steer clear of any trouble with them until the seventh game of the 1945 Stanley Cup Final between the Red Wings and Toronto Maple Leafs. The game was tied late in the third period when I called a penalty against Detroit. Toronto went on the power play and

Babe Pratt

scored to put the Leafs ahead. Toronto won the Cup and that infuriated Adams and Norris. From that point on, every year I'd be sent for an eye examination. In my opinion it was at Norris' instigation. Actually, the fact that Norris and Adams weren't fond of me was the greatest thing that ever happened because it meant that the other five owners were for me."

As you got more experience, how did it affect you?

"My (eye) condition didn't hamper me. I had 20-20 vision in my good eye and I was on top of the play. I didn't have much trouble from the players, except for a couple; namely,

'Rocket' Richard

of the Montreal Canadiens and

Ted Lindsay

of the Red Wings. They gave me the toughest time, although I never thought they were picking just on me. It was because of their personal makeup; they would have done it to anybody. Richard was the fiercest competitor in any sport. If you weren't on his team, you were the enemy. This would apply to the referee giving him penalties. Lindsay was the same way; an intense firebrand."

As a New Yorker, how did you get along with Rangers fans?

"Every once in a while, during the mid-1940s and a bit later on, there was a suggestion that I leaned over backwards to give New York a hard time because I didn't want people to think I was rooting for the team I once had hoped to play for. On the other hand, I sometimes got criticized for being a 'homer' simply because I came from the city. One thing I know for sure -- I wasn't a 'homer' anywhere I worked. Surprisingly, I never had a tough time in Montreal. I'm smug enough to think that I did well there because the fans know the game. Likewise, I always was well-received in Toronto. For me, the toughest rink was Chicago Stadium. I don't know why. I just never felt comfortable in that big arena."

How did you anticipate trouble in upcoming games?

"One way was to read the papers in the city where I was to officiate. Once I had a game lined up in Boston and noticed photos of the Boston players with cuts and bruises all over their faces. That made up my mind how I was doing to referee the next game in Boston. There was only one thing to do -- crack down early in the game with penalties. As it turned out, I called 17 penalties in the first period, five of them against

'Wild Bill' Ezinicki

of Toronto. After his fifth penalty, Ezinicki said to me, 'Bill, what are you doing? What the hell are you doing?' I said back to him, 'What would you do if you were in my position?' Ezzie shot back, 'I'd do the same thing!'"

Did a player ever come to your defense?

"

Jimmy Thomson

, the Maple Leafs defenseman, once did in the very same game against Boston. Earlier in the game I had given him a misconduct penalty. Just as Jim got out of the penalty box I had to get out of the way of action by hoisting myself on the boards. (There was no protective glass in those days.) As I did that, a Bruins fan hit me over the head with a rolled-up newspaper. He hit me so hard that I was knocked out cold. Just as I recovered, Thomson skated over to me and pointed toward the seats at the guy and we had him thrown out of the arena. It proved to me that while players may disagree with the referee, they don't want fans interfering with their game. As for the fan, I got a letter from him a week later apologizing."

NHL President Clarence Campbell had been a referee. How did he help the officials?

"One of the first things he did was eliminate hometown linesmen and switch to linesmen who travelled around the league just like referees. That eliminated the 'homer' possibilities. Before Campbell took over, if a referee called a penalty he was sure to have 10 people around him arguing. Campbell changed that so that only the captain or the alternate captain could discuss the penalty. Then the circle was added around the penalty timekeeper's area to keep players from interfering with the referee when he announces the penalty."

What aspect of your officiating gave you the most pride?

"I was the one responsible for developing the arm signals that the NHL eventually adopted. I started using them from almost the first day I was in the League. They were only made official the year after I retired. When I look back at all those years in the NHL, I know I'd do it all over again the same way. Hockey has been great to me, and I like to think that I contributed as much to it."

How did you enjoy doing color on radio and TV for Rangers games?

"Frankly, I enjoyed it more as a broadcaster than when I officiated. There were times when I found myself in a rooting capacity -- and really, I liked that. Considering all the years I was blowing a whistle, in my new job as analyst, I was able to sit back and really watch a hockey game. Once in a while, during a broadcast, I'd find myself yelling at the referees; not that I was particularly proud of that. But I never called a referee a 'blind bat,' because I knew I'd be only half right saying it!"