World's Longest Hockey Game enduring passion for Oilers optometrist

Players compete for 251 hours on his rink in latest record-setting cancer fundraiser

"He told me to keep kids out of the Cross," said Brent Saik, the 49-year-old optometrist for the Edmonton Oilers, referring to the Cross Cancer Institute in Edmonton. "He knew his time was up but he wanted me to try to keep them out of hospital."

Saik promised to do so, and it has tested his resolve more than he or anyone close to him could have ever expected.

After organizing a few baseball and golf tournaments to begin fulfilling that promise, Saik got the idea to raise funds by breaking the record for the world's longest hockey game.

That was 15 years ago, and in that time he has organized and played in six versions of an event -- the most recent having been held Feb. 9-19 -- that is glorious and grueling, a celebration of hockey, charity and the human spirit. An outdoor event that tests the will of the 40 players who lace up their skates and take the ice for 11 days, practically playing 24/7, all to help others.

© Andy Devlin/Getty Images

But for Saik, that physical toll is nothing compared to the emotions he went through while he was preparing for the inaugural game in 2003, when the players set the record at 82 hours.

"As we were setting it up for that game in 2003, for an 82-hour try at that record, my wife Susan got diagnosed with cancer and just a few months after we played the game, she died," Saik said, tears flowing. "So here we are. I still can't tell the story without crying."

No doubt he has told it countless times, given the event's increasing popularity. Through the first five games (2003, 2005, 2008, 2011, 2015), the group raised more than $3.4 million (all figures Canadian), mostly from individual donations. The players themselves spearhead the effort, soliciting donations from family, friends and colleagues.

© Andy Devlin/Getty Images

This year, $1.2 million has been raised with a goal to reach $2 million to help the

Alberta Cancer Foundation

and the Cross Cancer Institute establish the PROFYLE program in Alberta (it is already in place in other provinces). PROFYLE, started by the Terry Fox Foundation, aims to give children, adolescents and young adults who are out of conventional treatment options another chance to beat cancer by documenting and sharing a molecular profile of their tumors.

The results reveal the true state of Saik's commitment.

"Everything that we've tried to do with this game is based on children with cancer," he said. "The first piece of equipment that we bought, after raising $150,000 in that first game, was one with some kind of centrifuge and they told us in the first month it diagnosed 11 kids with liver cancer that normally wouldn't have been diagnosed."

How rewarding was that?

"I just sent that note to everyone else, and that's why everyone is out here all the time," he said.

\\\\

© Andy Devlin/Getty Images

This year, the 40 participants played for 251 hours, 9 minutes on Saik's property, known as Saiker's Acres, east of the Edmonton suburb of Sherwood Park, where the game has been held since 2008. That is longer than the total of 250 hours, 37 minutes, 7 seconds achieved indoors by a cancer fundraising group in Buffalo from June 22-July 3.

Saik and friends had held the previous mark; they set it for the fifth time in 2015, at 250 hours, 3 minutes, 20 seconds.

To be recognized by the Guinness World Records for the longest game, there are many regulations and the verification process can take six or more months. (The Buffalo game from 2017 is not yet recognized by Guinness.)

A real game with regular hockey rules and four on-ice officials must be played with two teams of 20 players. Five skaters and a goalie must be in play at all times for each team, and a video feed must be provided to Guinness officials. Once the game starts, no participant may leave the property until it's finished. If someone is injured and can't continue, no substitutes are allowed. Each player must be photographed on the ice at the beginning and end of the game.

The ice may be cleaned and resurfaced for 10 minutes after every hour of continuous play.

All of that dictates a schedule for the players that involves four-, five-, or six-hour shifts on duty, alternating with rest and sleeping periods. Most days, each player will play between 14 and 16 hours.

To share the burden and try to maximize whatever rest is possible, the group tries to schedule six skaters and a goalie per team for each hour of the game so that there is always one substitute skater to relieve a player who is tired.

© Andy Devlin/Getty Images

During rest periods, after showers, medical treatments and meals served up by round-the-clock kitchen volunteers, most of the players will sleep in RVs parked in a row on the wooded hill that backs up against Saik's house.

The commitment to participate for about 11 days borders on mind-boggling.

When he confirmed his attendance a few days before the start of the event this year, the game's oldest player, 56-year-old Jouni Nieminen, texted Saik, telling him that his doctor had approved him to play.

"Brent, it's like this," his message read. "I'm overweight, my back hurts, my knees hurt. My kids ... my wife, she said if I play she'll divorce me, so yeah, I'm in."

© Andy Devlin/Getty Images

And if that commitment and schedule weren't difficult enough, Mother Nature is often a fierce opponent.

This year, the weather was colder than normal. The game began on the morning of Feb. 9 with a temperature of 20 below zero Farenheit (29 below zero Celsius).

Beeswax is in high demand on such days. Rubbed on exposed facial skin, it's great at fending off frostbite.

With a little help from bees wax duct tape can fix everything!

— World's Longest Game (@longest_game) February 12, 2018

To donate: https://t.co/KYSBNwbWzc#worldslongestgame pic.twitter.com/XGKRj373vO

As for other tips to brave the elements, the veterans of the game have gotten smarter over the years. Many tape their feet before lacing up their skates, to keep dreaded blisters away.

"The first game, the whole game was tough," Nieminen said. "We all went hard and we were all tired, [with] blood in our socks and no (medical) help but we just had to get through it. To me, that's always going to be the hardest one.

"I use special skates, bigger because your feet swell over the [11] days. Some guys tape a hot pack on top. Some guys go to the camping store and buy the booties and cut out the bottoms, and put them on top of their skates. That works really well. And guys now have heated vests and heated gloves. I don't do any of that. I use old garden gloves, might throw in a hot pack if I need it. But everybody's got something."

Still, it's snow, not cold temperatures, that may make for the toughest playing conditions.

"It blows and sticks in your face, freezes on your face," said Curtis Sieben, 42. "Cold, you can for the most part deal with it. It hasn't bothered me this year. You don't want to come inside when it snows because basically when it melts, you freeze. Your outside layer gets wet and it's frozen stiff. I came in from that, and my balaclava was rock hard. I had to pull at it for five or six minutes just to get it over my head and off. It was a big crusty cast."

Sieben has learned he must tape his feet, and to bring the biggest pair of boots he can find for his off-ice time.

"I see the young guys, they say their shoes are absolutely killing them," he laughed.

© Andy Devlin/Getty Images

The players' willpower should not be underestimated.

"The hardest part of the game is waking up and walking down the hill from the RV and getting your gear on," said Doug Greschuk, 50.

Goalie Jannes Freerksen, 40, said having a personal strategy is a priority.

"You have to layer and play it by ear," he said. "If you start getting too hot, you take off a layer. But if you're cold, you're in trouble.

"A lot of the guys have electric jackets and gloves. A little too high-tech for my taste."

Freerksen said the fifth day is crucial for him.

"If you get past Day Five, your body will just go on and on," he said. "I'm not sure it's a mental thing because you can see the end or maybe your body just adjusts to the time and very little sleep. It's a high-carb, low-sleep diet. And you just keep going."

\\\\

Saik is remarried. His wife, Jenelle, also an optometrist, shares his practice, and they have a 6-year-old son, Jesse.

Jenelle was a player in the game this year for the third time.

Brent and his wife! Have a great Valentine’s Day!

— World's Longest Game (@longest_game) February 14, 2018

To donate: https://t.co/KYSBNwbWzc#worldslongestgame pic.twitter.com/GTKqVrDQIQ

"She's been a champ," Saik said. "Getting the game organized, I'm working about two days a week right now. I'm not worried. My wife is way prettier and better at the job than I am."

The Alberta record-breakers have played in three locations where Saik has lived in the county. The current site is likely permanent, he said, given that he has built a clubhouse next to the regulation outdoor rink.

The two-story building is about 3,000 square feet, all windows and glass doors facing the ice. It houses a full locker room for 40 players, a full medical room used by doctors, nurses, chiropractors and massage therapists during the game, and a warming room connected to the players' bench next to the ice, featuring a memorial wall with photos of Terry and Susan Saik, and dozens of other cancer victims remembered by the players.

"The first time (in 2003), maybe it was a bit of a lark to just go play, but it's grown to the point that we built that building instead of a [new] house," he said, referring to the decision after the 2008 game to remain in the existing house on the property.

For that game, the players slept and changed in one of the three garage bays on the lower level, sharing space with Zambonis.

Saik says he's done building after spending a half-million dollars on game infrastructure and amenities on his property, including the rink, lighting, wiring, clubhouse and the two Zambonis.

Huge snow storm this morning

— World's Longest Game (@longest_game) February 14, 2018

To donate: https://t.co/KYSBNwbWzc#worldslongestgame pic.twitter.com/eQeGckTAEI

The investment goes far deeper than money.

There were six new players this year taking the torch from those who retired because of their health or age. There are more than 250 candidates on a spreadsheet Saik keeps, most of whom he has met through his practice. To make the cut when there is an opening, a player must have a close connection to someone who has had cancer.

"Because when you start doing the [cancer treatment] process, it's horrible," Saik said. "This is fun. That wall with the pictures ... ultimately, if you didn't believe we could cure cancer, we probably wouldn't do it. That may be an odd statement but I don't think we're here just to try something.

"Everyone here is invested in some way."

\\\\

The list of players who have been in all six games has dwindled to five: Saik, Randy Allen, Darcy Humeniuk, Sieben and Nieminen.

"It's been my last game since 2005," Nieminen said, "but this time I'm really thinking, that if this is my last one, I want to really enjoy it, soak it in, listen to the stories and dance by the fire, that sort of thing."

The Finland-born freelance journalist moved in 1981 to Port Coquitlam, British Columbia, where he intersected with a story and a life that have impacted so many in the fight against cancer.

Fox, three years after having his right leg amputated because of bone cancer, attempted to run across Canada in 1980 to raise money for cancer research. His Marathon of Hope ended after 143 days and 3,339 miles near Thunder Bay, Ontario, when cancer had spread to his lungs. Fox died June 28, 1981, at age 22, never completing his run. He is regarded as a national hero and cancer warrior who continues to inspire, even into the coldest winter days outside of Edmonton.

"My cousin Jari, he used to watch Terry Fox run, and Jari passed away (from cancer), too," Nieminen said. "I met [Fox's] brother and his dad, I went to school with some of his friends. I feel a connection for sure. That guy was something else, this little Irishman who wouldn't give up. He made the Simon Fraser (University) basketball team because he tried so hard, that's the kind of guy he was. No compromise, no matter what.

"It's kind of amazing."

More recently, Nieminen's friend Doug lost his wife, Sonia, to cancer.

"So now I'm playing for her, too," he said. "It never ends. So I have to play."

Nieminen said that of the six games, the 2008 version had the most extreme weather he could remember. The first two days of the game were played in bitter cold.

The official recorded temperature at Edmonton International Airport at the game's start was 33 below zero F (36 below zero C), and several players from that game mentioned the wind chill being 60 below zero F (51 below zero C) during that stretch.

Conditions did moderate after that wicked start.

"That was survival mode that year," Nieminen said.

\\\\

Sieben is another of the originals who has persevered through the years.

"We figured in [2003], 82 hours? We'll just stay up for 82 hours," he said. "That was not right. After the first day, we realized it wasn't going to work. All we had was equipment, a cot in a garage, eating, sleeping and dressing in the same place and no showers."

Still, he said whatever the challenges, they are minor in the big picture.

© Andy Devlin/Getty Images

"My father (Joe) passed away from cancer; my uncle, too, and a friend, Rhonda (Kasowski), she just passed away a couple of weeks ago after that battle for four years," Sieben said. "She was looking good last summer, then all of a sudden you don't see her for a couple of months and then bad news. Cancer just decides when it wants to take you. That's the tough part.

"But of course, here, it's about the love of the game. The atmosphere here can be great. During the week here, there will be a couple of days where buses of school kids come, every grade, to watch. That's awesome here. It's so nice to see the kids."

\\\\

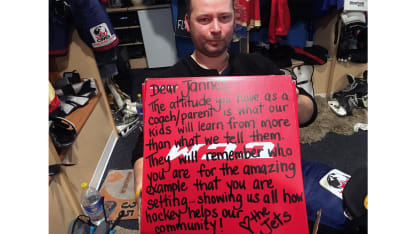

In the middle of the night, when Day Two of the game was becoming Day Three, and Bryan Adams' "Lonely Nights" was blaring over the speakers, Freerksen, one of three goalies for the white/yellow team, had just finished a five-hour shift.

His 11-year-old son, Noah, arrived at Saiker's Acres a few hours earlier with a care package of food, goodies and warm socks from his peewee hockey team.

But it was the top of the package, a skate box, that had him near tears.

"Dear Jannes," the note said. "The attitude you have as a coach/parent is what our kids will learn from more than what we tell them. They will remember who you are for the amazing example that you are setting ... showing us all how hockey helps our community! [Love] the Jets."

He has played in five of the six games, the past three as a goalie.

"It's such a neat event," said Freerksen, 40. "It's not just the guys you see. There are some kids that come out, some cancer survivors. There's a boy ... Brendan [O'Callahan] -- he was a cancer survivor and he keeps coming back every game. Everybody knows Brendan. He signs jerseys for us and it's a pretty neat experience."

Freerksen said he saw the first game in 2003 and knew he had to get involved.

"When I was 9, my dad (Feike) was diagnosed and passed away from lung cancer," he said. "When I was 13, my mom (Annelene) was diagnosed and passed away.

"My wife Trisha worked for Brent back some years, and when they played the 2003 game, we stopped in and thought it would be a pretty neat thing to get into. In 2005, they said they were going to try to break the record again and raise a whole bunch of money, so I had to get in."

Though he was not sleeping so well this year, Freerksen was an ideal teammate. He took a few hours as a skater when he wasn't scheduled to play. He scored 13 goals.

The power of the group has a hold on him, and other players.

"Every year, after it's over, I say I'm never playing again," Freerksen said. "Every time. And you just keep on coming back even if collectively this group is getting older and heavier."

\\\\

Players in the World's Longest Hockey Game have been touched by O'Callahan.

He is equally touched.

"It's truly inspirational for people to push their limits physically and mentally [not unlike] patients who endeavor to deal with their treatments and struggles," said O'Callahan, a 22-year-old fourth-year student at the Alberta College of Art and Design in Calgary. "It's a really, really good thing for society and our community that people can push themselves like that. Whether it's a hockey game or any situation you encounter, you can overcome and achieve great things through hard work and patience."

O'Callahan was diagnosed with leukemia at age 2 and, after 18 months of intense treatments, beat the disease by the time he was 5.

His diagnosis came well before the longest hockey game, but he was aided by Saik's early efforts to fulfill his promise with baseball and golf fundraisers, having been treated at facilities helped by those events.

O'Callahan is flattered he's remembered by the players in the game, and even more flattered that he has been the one signing autographs.

"That's cool," O'Callahan said. "Over the years, for them at least, they know there's this reoccurring person that comes back. For me, it's nice to kind of be remembered for being this idol to people who make a difference.

"Even though I don't remember all of the experiences, them acknowledging that I've survived this is a nice reward in a sense, that they still honor and acknowledge my struggle. The action of signing (autographs), it's pretty cool to look back and they have all those jerseys, such a nice souvenir to have."

O'Callahan, who has attended the game most years, wasn't able to this year because of school commitments. But the impressions of previous visits, when he'd see up close the physical ordeal involved with this hockey marathon, stick with him.

"Very humble guys," O'Callahan said. "And very understanding of why they do what they do and who they do it for. My presence and other cancer patients' presence is why they do what they do. It's to skate for people and to make them feel better, more for encouragement than anything."

He said that Saiker's Acres is like a highway of inspiration that flows both ways between players and cancer survivors.

"I think they see that and it makes them more inspired," he said of the players. "When I've been there, they're always asking about my story, what I'm doing now. They are so interested to see they're making a difference. They're such super nice and super engaging guys with all the survivors.

"And I've never seen a grumpy person out there."

\\\\

Greschuk is one of the six originals from 2003 who played the game this year, his fifth appearance. He missed 2015 because of a blood infection.

"I lost a lot of weight and had to bow out," Greschuk said. "The [first] morning of the game, I came out here, I was excited still, and I met the guy who replaced me and I shook his hand and said, 'Hey, have fun but not that much fun because I'm coming back."

He kept his promise.

"I just love the camaraderie," he said. "It's my fifth game. I love the guys I play with. I grew up playing a lot of hockey. It takes me right back to that. There's no better universe for me."

Every player in the game has a nickname, awarded by his fellow players and displayed on the name bar of his jersey.

"In 2008, we dressed on church pews (for benches) and I ended up getting a sliver off a church pew, so that's why I'm Altar Boy," he said.

Greschuk is unique in another way at Saiker's Acres.

The defenseman is the only player in the game to be drafted; he was selected by the Pittsburgh Penguins in the 11th round (No. 212) of the 1985 NHL Draft, two spots ahead of Hall of Fame forward Igor Larionov, who was picked by the Vancouver Canucks.

© Andy Devlin/Getty Images

The Merrimack College graduate took a different career path, though. He is a successful industrial and commercial real estate broker in the Edmonton area.

Greschuk marvels at how well-known and well-regarded the World's Longest Hockey Game has become, almost an institution in central Alberta.

"The animal that this has become is amazing," he said. "The sincerity of the game remains the baseline but it's gained such momentum in the community and it's a grass-roots initiative. That has not changed."

(To that end, the game this year even attracted Oilers forwards Connor McDavid and Ryan Nugent-Hopkins, defenseman Darnell Nurse and coach Todd McLellan, who visited on their own time, chatting with the players, posing for photos and signing autographs. Edmonton donated signed jerseys and sticks, and game tickets for seats and boxes, as prizes for the silent auction.)

Greschuk hasn't had quite the ordeal with cancer that other players have experienced, but that has not tempered his enthusiasm for taking part in the game.

Thanks for coming!

— World's Longest Game (@longest_game) February 13, 2018

To donate: https://t.co/KYSBNwbWzc#worldslongestgame pic.twitter.com/eetBWh2oHP

"Both my parents had battled with cancer but have survived those," he said. "We've had some deaths in our family, like my sister's mother-in-law from cancer. We've had nothing devastating in our lives but it's always affecting people.

"I didn't do the last one and I couldn't wait to play this game, even knowing the valley that we go through. There's no better war I'd rather go through than with these guys."

And when the war was over for this year, Greschuk had a smile on his face when he joined wife Jodi, daughter Ava and son Roan for a long family hug under the fireworks.

\\\\

Family is not the reason TSN radio morning show host Dustin Nielson got involved in the World's Longest Hockey Game. But it's why he's committed to the effort, having finished a third game as one of the top fundraisers and been the leading scorer this year with 323 goals.

For the record, he helped the red team to a 1,830-1,691 win against the white/yellow team. Nielson collected per-goal pledges through his radio show of $125. He also received other donations, and expects to raise $80,000.

"They were short guys in the 2011 game and they called the radio station and asked me," Nielson said. "I just love playing hockey and it's a neat thing, but I didn't know what it was really about until I got out here.

"Once you get here and realize what it's about, see people coming out here to watch or help ... so I stayed in for that but I also felt a responsibility because I have the opportunity to raise a bunch of money by being on the radio."

© Andy Devlin/Getty Images

Nielson, 36, and his wife, Tammy, have a 2-year-old son, Marshall, and a 1-year-old daughter, Elizabeth. Having children made him want to contribute even more.

"I met this kid named Thomas at the Stollery (Children's Hospital, in Edmonton) doing a visit," he said. "His dad listened to the show. They came out here in 2011 and I've stayed in touch with him since then and he's been through a bunch of chemo treatments and is healthy now. It's those type of things.

"At the opening ceremonies there was a kid who's had 52 chemo treatments. It's ridiculous seeing people like that coming out here, so this (playing) is nothing. Now that I have kids and I'm raising money for pediatric cancer research, it hits home for sure."

Nielson is known as Pop Tart for the game.

"For my first game out here, I like Pop-Tarts and I don't really get to eat them at home very often," he said. "So I brought out a box of Pop-Tarts and I fired up the microwave in the [RV] to warm up the Pop-Tarts and it kicked out the power breaker for all the trailers up there in the middle of the night. So that's how I became Pop Tart."

\\\\

Saik's daughter, Angelica, was 18 months old when Susan died of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The World's Longest Hockey Game is the gift that allows the 16-year-old to continue to hear all about her mother.

"Angelica grew up with this," Saik said. "She never knew her mom. Around this time, she gets to know her mom because there are lots of people telling stories about Susan.

"She's 16 and now a big part of getting this done."

© Andy Devlin/Getty Images

Angelica, an 11th-grader at Archbishop Jordan Catholic High School in Sherwood Park, again took a week off from school to be the official gofer for the game.

"I go get gas for the Zambonis, go to Home Depot for a part to fix them, go get ice, whatever is needed," she said.

Angelica is on a similar schedule to the players and key support staff among the 800 volunteers who make the game run smoothly, playing/working and sleeping in shifts day and night.

"Not much sleep, but it's enough that you can walk and function," she said. "I love how all the people come together and help out. It's cool to see how it all unfolds from a month ago to today."

All the while, what's seemingly impossible, a bond with her mom, becomes a little stronger.

"I think it's kind of cool that they knew my mom and then they like to tell me stories about stuff," Angelica said. "I'm sure the players would not like me saying this but I don't like this when it ends. I like when people are here."

\\\\

The volunteers pave the way for the amazing feats of stamina and fundraising from the game. Strong connections and relationships are everywhere.

Susan's dad, Dennis Jettkant, continues to be involved. He's the head of maintenance, directing a crew of hardworking friends.

Terry Saik's best friend, Harvey Stebanik, is in charge of the propane fuel and heat for the RVs.

Brent Saik's best friend, Brad Frunchak, is in charge of the ice and ice resurfacing crew that keeps the game on the strict round-the-clock schedule that Guinness requires. They go through 5,000 gallons of water per day to keep the ice in good condition.

© Andy Devlin/Getty Images

Saik's mom, Vikki, oversees the kitchen crew. He said their work is exceptional. His proof? He's never lost weight during the event, he said with a laugh.

His aunt Eileen Ursuliak is in charge of nurses and the medical team schedule.

Perry Zyla looks after the round-the-clock schedules for the referees and scorekeepers.

And Brenda Martin, Brent's sister, takes on the unofficial role as chief operating officer.

"It's like a little city here," Martin said on Day Five. "It may sound weird but the first two days is hard because you have a certain lifestyle. Now you have a different lifestyle for another week. But they're into their routine now. Their bodies are getting used to it now."

This year, the jerseys, red and white/yellow, were a tribute to the 1952 Olympic gold medalists, the Edmonton Mercurys. On one sleeve was a black band with No. 73, a tribute to Martin's husband Jim, who died in November 2016.

Jim Martin, who wore that number, played in the 2015 game and was responsible for building the 40 players' schedules.

"He had four strokes and a heart attack but he was still able to figure out the math on this schedule for them back in 2015," Martin said.

Those involved say inspiration and energy from lost loved ones is all around.

"Honestly, everyone enjoys this," Martin said. "But enjoy, I guess, is not the right word. They endure it, go through this. Look on the players' bench, that wall of pictures, those people and what they had to endure for their years of chemo and all that, well, this, some sleep deprivation or a blister on your toe is nothing compared to all that. People look over there and say, 'This is nothing. We can go through this.'"

Martin, who runs Saik's office and describes herself as a Type A personality, has an energy that's easily identified. Having witnessed her brother's determination for years, she has a good grasp of what drives him.

"Because of Brent ..." she said. "He has his vision. We're one of those families ... we can live together, work together 24/7. You know he's never giving up, so we figure out what to do so we can get this done. He thinks of all the things we need and we get at it.

"It was 2 o'clock in the morning and the game a few years ago was going on, before the rink house, and it was cold and this lady was sitting out there by herself on the bench, watching," Martin said, her voice cracking again, the tears returning. "Brent came over to say 'hi' and she told him her husband had just passed away, that he had wanted to come to watch but he couldn't. She had come directly from the hospital. She just wanted to be there.

"It's those kinds of stories that tell you why they're doing this. And if you're tired and you forget, you remember that woman's face, like most of these guys who were on that shift.

"It was almost like an angel showing up for them."

\\\\

© Andy Devlin/Getty Images

The rink at Saiker's Acres has ice all winter, every winter. Saik is happy to have guests, recreational teams or kids teams. All that's required is a donation to any charity for $1,000 and the place is theirs for a session or game.

"It would be kind of dumb to have this thing and [not share]," he said. "I just have a rule for kids programs, that the kids have to help raise the money. I don't want a check from one dad for the $1,000. It's good that the kids go around and ask their family, their uncles and aunts and friends for something, then the parents can put in the rest."

The tears came again when Saik was asked what's in this for him.

"Oh, it's always tough to do this," he said. "Obviously I want to cure cancer but [what's] in it for me is this: I love this. I love these people that come here. I love telling you that some dude named Dylan that I don't know dropped off his skid-steer and a bunch of firewood to help us today.

"I love that there's so much that we can complain about today, about anything, but I've never seen anybody complaining out here. Nobody does. Everybody's happy. Everybody works hard at it. There's a lot of sitting and visiting, catching up, too. And everybody that comes here, it's not so much for me, but what's in it for me is all these people coming here to do this stuff, to help."

Does he see an end for the World's Longest Hockey Game?

"It's an easy answer," he said. "The game doesn't ever burn out for the people doing it. Ten years from now, should we only raise 10 grand, we'll still do it. Money, yes, we want to do that and it's important to us.

"But the premise for doing it ... the byproduct is raising money. We're doing it for another reason and that reason will never burn out."