Gerry Helper couldn't have said it better from the very start of our conversation.

"I've tried to think it through in my mind, and I guess the big picture - it's very seldom that reality is better than a dream," Helper said. "But, as I look at my career, that's exactly the case."

I, and so many others, are in Nashville because of Helper. He hired me at 23, my first full-time job out of college, to work for the Predators, to help tell the stories of those on the ice and off who make their mark with this team, this franchise.

Now, over seven years after he was on the other end of one of the best phone calls I've ever received, it's time to tell his.

Helper's Impact on Preds, Hockey Worthy of Praise as Retirement Arrives

Predators Senior Vice President Looks Back at Time in Nashville, Beyond After 43 Years Working in NHL

© Abby Helper

Today, Helper, whose 43-year career in hockey began in Buffalo during his Christmas break of 1978 as he sat in the press box as a college senior and took stats for the Sabres coaching staff, has made the decision to retire from the professional ranks.

Helper, who has spent the past 24 years in Nashville, was one of the few "Day-Ones" remaining, someone who has been with the franchise since before the very first puck drop in October of 1998. The average fan likely doesn't know his name, but as far as folks who prefer to remain in the background are concerned, the Buffalo native has had about as much of an impact on hockey in Nashville as anyone - but he knew his role, too.

"I always had the mindset of as long as the two teams and the four - well, three back when I started - but four officials are here, the rest of us are all just extras," Helper said. "They're dropping the puck at 7:08 whether the rest of us have our stuff in order or not. So, keep in mind who you are and where you fit in. You're just part of the team, you're not the one the game revolves around."

This is true, but for all these years, Helper - whose surname is apropos in so many ways - helped to make things go.

And a life in hockey that has taken him all over the continent began simply enough.

…

A proud attendee of St. Bonaventure University in the mid-to-late 1970s - and a loyal Sabres fan - Helper's first taste of being on the inside came as he prepared to write a senior thesis and decided he wanted to speak to Buffalo's public relations director at the time, Paul Wieland.

"I interviewed him around Thanksgiving of my senior year, and I ended the interview and just asked him, 'Hey, I'm still trying to figure out what I want to do with my career, anything I might be able to come in during my Christmas break and learn about this business?'" Helper recalled. "And thankfully, he was a St. Bonaventure alum, and he was a great guy, and he basically looked at me and said, 'Well, come on in, we'll figure something out.' And so, I'm thinking worst-case scenario, I'm going to see five games for free."

Helper did indeed get in for free, but he was put to work, even though it didn't seem like anything he was doing was all that strenuous. In fact, the so-called "work" was quite enjoyable.

When those five games were up, Helper asked Wieland if he could continue to swing by through the end of the season. Wieland agreed, and Helper, who didn't have a car of his own, found rides and bargained with friends for help making the 90-minute journey from school to the Buffalo Memorial Auditorium through the spring semester prior to graduation. During that time Wieland had been hoping to hire a public relations assistant, and in the summer of 1979, he received approval - and Helper was first on the list.

Fresh out of school, Helper began by working with legendary figures he had been cheering for in the stands just a few months earlier. Players like Gilbert Perreault and Rick Martin, plus Scotty Bowman, the winningest head coach in NHL history, were now Helper's co-workers in a way - and what a start it was.

"This is my first exposure, and I couldn't work enough," Helper said. "I wanted to be there all the time. That was what I wanted to do to be involved, to be part of it. And fortunately, I can look back and say from that day on I never viewed it as I had to work. It was, I get to work in the field I wanted to be in."

© Abby Helper

Helper was with the Sabres through 1986 before moving to work at the NHL offices in New York City, first as the League's director of information, and then as the director of public relations.

That time spent with an overarching view of the member clubs gave Helper the ability to not only learn how the League conducted business, but how those relationships were best formed and maintained with the teams themselves. Helper was directly involved in a myriad of topics during that time, but he also helped to introduce the NHL's first All-Star Skills Competition including fan-favorite events still around today like Fastest Skater and Hardest Shot.

Being involved on the PR side of things also allowed Helper to have an ear to the League's expansion initiatives. In the late 80s, new clubs were on the horizon, and in December of 1990, the NHL announced two teams - the Ottawa Senators and Tampa Bay Lightning - were set to join the League.

Around that same time, Helper began to realize he was missing something.

"I had reached a stage where when you work for the League, you're involved in the game, but you clearly don't have a rooting interest or a vested interest in the outcomes per se," Helper said. "As John Ziegler, the League president when I was there used to say, 'When you're at the League office, you root for sellouts and ties.' You can't have a rooting interest. But if you've been at a team and you go to the League, you might, after a while, have a time where you kind of miss that winning and losing part, and I did."

In 1991, Helper joined the Lightning, almost two years before they were set to play their first game. Those experiences gained with an expansion franchise - including finding a place to play - gave Helper just about all the knowledge and know-how he needed to aid a club from starting as a letter of congratulations to a full team of players on the ice.

© Abby Helper

In Tampa, Helper also made a life-long friend in Terry Crisp, the man hired to be the team's first head coach. The PR guru was there to assist Crisp in dealing with the media and beyond, but he also offered some advice to the bench boss.

"I used to say to him when we were in Tampa, and I didn't mean it as any commentary whatsoever and his coaching ability to Terry…but I would say, 'If you ever tire of coaching, you've got a future in broadcasting,'" Helper said.

Eventually, Crisp's time in Tampa came to a close, and with new ownership coming in after a new arena was built downtown on the water, Helper knew his stint was likely about to run out, too.

But 700 miles north in Nashville, Tennessee, a new opportunity was brewing.

…

The expansion experience Helper had in Tampa was still appealing, and he thought perhaps he could do it again somewhere else.

In June of 1997, the NHL was ready to expand once more, and teams were awarded in Minnesota Columbus, Atlanta and Nashville - and Helper knew exactly where he wanted to be.

Soon after the announcement was made, the Predators named Jack Diller as the franchise's first president, and Helper saw his opportunity. He knew the governor of the Lightning at the time, David LeFevre, was friends with Diller, and Helper asked if a phone call might be made on his behalf.

LeFevre obliged, and in October of 1997, Helper, his wife and their two young daughters, made the move to the Volunteer State. From the moment he stepped into his office inside what was then simply known as the Nashville Arena, there was work to do.

In five to six months, as Helper recalled, the team had to sell 12,000 season tickets to ensure the initial stability of the franchise. Announcements of the logo, team name, jerseys and the like helped drum up interest, and the goal was met just before the deadline in the spring of 1998.

© Abby Helper

But Helper knew if the team was to be successful from the start, the on-ice performance wouldn't necessarily be the driver. Expansion rules were different back then, and a new NHL team wasn't expected to be competitive right away. Two areas Helper was given responsibility for were community relations and youth hockey - and he knew those departments held as much importance for an expansion franchise as anything else.

"The whole thought was if we can get kids playing hockey, whether it was on ice or street hockey, we could turn them into fans, and they would want mom and dad to take them to a Predators game," Helper said. "Conversely, players we had in the early days were so important because they knew they were here for more than what they did on the ice. They were the missionaries, if you will, of trying to establish the franchise in this market. You look at what we asked players like Tom Fitzgerald, Greg Johnson, Kimmo Timonen and so many others to do in the early days off the ice, they helped set the foundation, because they did the school visits, the hospital visits, the clinics that allowed us to connect with more people in the community.

"And then through the Predators Foundation where we were able to raise some money and award grants, that was a way to touch organizations throughout the community. And as we know, these foundations, these other community organizations have boards of directors, and if that board saw that the Predators and the Foundation were supporting them, they might feel a sense of responsibility to support us back. Those were two really, in my mind, important ways for the franchise to gain a foothold in a new market, especially a new market that didn't have a lot of exposure to the NHL."

The Predators have come a long way since then - on and off the ice - and Helper has had plenty to do with the franchise becoming a staple in the Nashville community. But he knew from the very beginning this was a special place, and when, as Helper calls it, the "greatest game in the world" came to town, there was always a chance for something great to happen.

"I could envision this 24, 25 years ago, but you never know exactly how it'll play out," Helper said. "But I have pride in playing a small part in it."

…

As one might imagine, Helper has more stories to tell than time will ever allow. Picking a favorite moment from his over four-decades of "work" is impossible, but a few stand out, like representing USA Hockey as a communications liaison at the 2010 Winter Olympic Games or hosting the first-ever playoff games in Tampa Bay and Nashville.

The marquee events in the Music City are near the top of the list, too, like the 2016 NHL All-Star Weekend and the 2017 Stanley Cup Final, but the 2003 NHL Draft, also held in Nashville, holds a special place for Helper.

Tasked as the organization's point person in working with the NHL to host the Draft, Helper was unsure of how the fanbase would show for the event. But when the late Jim Gregory belted out "Nashville" during the roll call, the crowd responded by - perhaps unsurprisingly - rising to their feet.

"And when he calls, 'Nashville,' the building erupted into a standing ovation," Helper laughed, reliving that relief over 18 years later. "Honestly, that was as proud a moment as I had because that was one of those - everybody was just so excited and proud that the hockey world had come to Nashville. And it was really a signature moment. We've had a lot since then, but that was, in my mind, that was the first."

Helper has been part of every single one of those instances in Nashville, but for the first time in the franchise's history, he's about to be looking on as a proud fan instead.

…

After being around a hockey rink almost every day for the past 43 years, Helper isn't quite certain yet what his days will look like in the months and years ahead, although he's certain his dogs are about to become the best-conditioned animals in the neighborhood with the amount of walks they're now set to receive.

There will undoubtedly be days of reflection ahead, and one of the first has seemingly already come and gone with our conversation that took Helper down a few thousand memory lanes. Not every day was easy, not every game ended in victory, but for a kid who wasn't exactly sure what he wanted to do over four decades earlier, Helper sure found his calling.

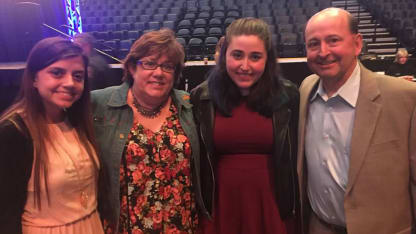

© Abby Helper

And in reflection, Helper knows just about everything he has in life is thanks to the game he loves.

He met his wife, Kim, in Buffalo at a Sabres practice. This past summer, they celebrated their 40th wedding anniversary. His daughters, Renee and Abby, were raised in Nashville, and the youngest now works for the team herself. Some of Helper's greatest friends, like Crisp and Voice of the Predators Pete Weber - a pair he brought to Nashville to call games from the start - and former Preds Assistant Coach Brent Peterson, were all met along the way before reuniting in Tennessee.

And then there are the memories and the experiences that can only come from working in the NHL, around the greatest players, coaches and staff members who are the very best at what they do.

And Helper was pretty darn good, too.

"I always tried to operate with integrity and character, because I do believe that matters," Helper said. "I hope people would say about me that he cared, that he was always loyal to his organization and his colleagues, and he gave it everything he had. I do think as I reached the end, I can look back and say I gave it everything I had."

"Back when I was in college, I dreamed of working in or around pro sports, but never in my wildest dreams could I have envisioned it lasting 42, 43 years. And to have the opportunity, when I look back at the stepping stones, to work for my hometown team, to work for the League office and to be part of two expansion franchises from Day One… But then also working with the U.S. Olympic Team, that's pretty special, all of those things wrapped up."