Skinner’s coach at the time, Paul Maurice, marveled at the rookie’s ability to evade defenders with his footwork and watched him get named to the 2011 NHL All-Star Game and later, take home the Calder Trophy as the league’s top rookie, with 31 goals and 32 assists in his first season.

“He was such an unusual skater, and I don’t know that I’ve ever seen a player like that,” Maurice said. “That whole idea of being able to open up 10-and-2 and change direction. I just remember in practice after he’d been with our team a little while and he had scored some goals with that move he has, all the guys were down in the corner trying it and none of them could do it. He is an elite skater and an unusual skater that I don’t know that the league has seen a player use that back-foot rutter the way he does.”

Maurice has seen many unique skaters in the NHL with his more than two decades of experience as a coach, but it was Skinner’s ability to use his skating and then tailor it into a plan of attack that still stands out to him to this day.

“It’s not just a straight line kind of skating idea,” Maurice said. “It’s a sideways, in-and-out, and buy time and open up ice for people around him, but also for himself. Again, I don’t know that I’ve seen a player skate like that.”

Commitment to the game

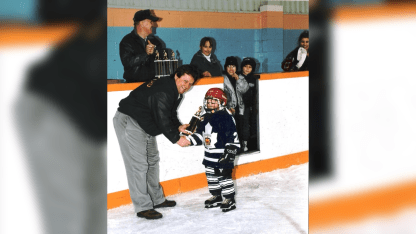

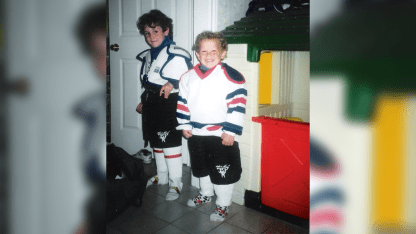

Skinner’s parents were busy raising six children who were in various sports, clubs, and activities. While the two committed their time and energy to being at every hockey game possible, they began to understand their son’s strong commitment to growth.

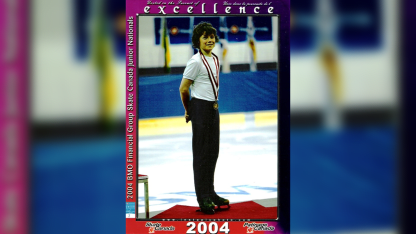

Campin remembers sitting in the stands with Skinner while watching his older sisters’ games, where he would often spend time pointing out specific plays and players to his mother, demonstrating his dedication to developing his vision and understanding of the game at a young age. Campin was in awe of Skinner’s impressive hockey IQ and vision and his ability to use his siblings’ games as learning opportunities to carry over into his own game.