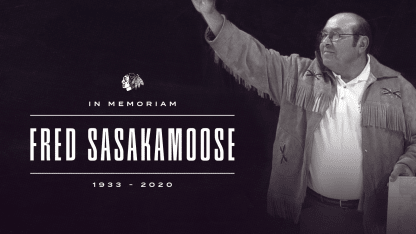

Editor's Note: This story was originally published on Dec. 25, 2020 and has been updated

When Fred Sasakamoose passed away recently, his remarkable saga resonated throughout the hockey community. Although he only played briefly with the Blackhawks, Sasakamoose defined a path to the National Hockey League for numerous Indigenous men, a legacy that justly elevated him to hero status in the First Nation.

"A trail blazer for our people," praised Jordin Tootoo, whose extensive NHL tenure ended with the Blackhawks during the 2016-17 season. "I had a nice career, and loved Chicago, where the younger of our two daughters, Avery, was born. I met Fred, and was awed just to be in his presence. Humble, great spirit, led by example.

THE VERDICT: Sasakamoose Paved NHL Path for Indigenous Men to Follow

Indigenous hockey luminary would've been 89 on Dec. 25

© Bill Smith/Getty Images

© Jeff Vinnick/Getty Images

© Getty Images

© Getty Images