Stan Mikita theorized that if he ever put his life story into words and presented it to some movie mogul, the script would be tossed back to him in a Hollywood minute on the grounds that it read like fiction.

But Mikita's extraordinary tale was real because he was real. He was the least pretentious superstar you could imagine. Nevermind how he handled the puck. It was about how he handled people. He cut his own grass, answered his own phone, and if you were a neighbor awakening after an overnight blizzard, you might peer out at your driveway and discover that it had been cleared by a snow angel.

As an icon in the Blackhawks' locker room, Mikita was beloved by the guys. Not by imposing his lofty status, he would mentor upcoming superstars like Denis Savard and Doug Wilson as willingly as he would talk to-and, just as significantly, listen to-- a fourth line winger. If you were a wide-eyed kid hoping to make the team as a rookie like Bob Murray, you would get a phone call in the hotel room of a strange city inviting you to dinner with Stan and wife Jill at their house.

THE VERDICT: The soul of the Blackhawks

Team Historian Bob Verdi writes a fitting tribute to who he calls the least pretentious superstar you could imagine

Stan never big leagued anybody. Bobby Hull, and rightly so, was hailed for signing autographs until the last fan received his cherished signature. But Stan was no slouch in that department, and his penmanship was immaculate. Stan knew Arnold Palmer, the golf legend who believed that if you're going to sign your name on a piece of paper, don't scribble it.

Maybe that's where Stan learned about this part of the job. More than likely, though, it was a reflection of a complete professional, meticulous and caring and genuine. He was an ambassador for the Blackhawks 50 years before they hired him as such and gave him the title. He was all about the hockey game, not the fame game.

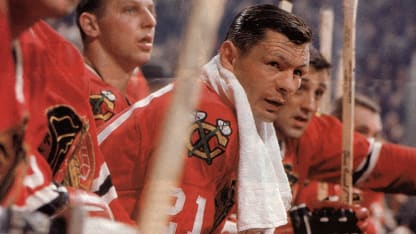

On the ice, of course, Stan was a handful for opponents. Always conscious of his moderate frame, he absorbed teammate Ted Lindsay's early advice about hitting them before they hit you. Stan took a pounding but responded in kind. On the back of your hockey card, they list height and weight but they don't measure heart. In Montreal, where Mikita vexed brothers Maurice and Henri Richard, they grudgingly referred to that Blackhawks' genius as Le Petite Diable. The small devil. What a competitor.

Off the ice, Stan was a common man. Funny, articulate, cerebral. The loudest part of him, besides a few of his garish sports jackets that looked like seat covers from an old Studebaker, was his laugh, a guttural and distinctive roar. And did he ever like to laugh. If you were around Mikita and you didn't laugh at his dry wit, you needed a note from your doctor. He was a human comfort zone.

Many a time, a certain sports writer would enter the locker room beneath the Stadium after practice. Six or seven ashtrays could be seen in cubicles, and there was Stan, reading the sports section under his Camel cloud. "What is this -------- you put in the paper today?" he would chirp. "Good thing the Tribune is absorbent. I have a leak in my basement."

Then, after the harpoon, came that impish grin and that laugh.

Back in the day, the Blackhawks often would gather as a group after practice at one of their joints for lunch and a couple beers. What fun they had, especially when Stan ordered his favorite delicacy, steak tartare, medium raw.

They talked hockey and told stories and Stan loved stories. If a certain writer had one about Harry Caray, Stan was all ears. When Harry was broadcasting for the White Sox, he and the writer went for dinner after a day game at Comiskey Park. They met about 6 for drinks, more drinks about 8, more about 10. The "meal" to that point was pretzels. By about 11, the writer was sleepy, but not Harry.

"Well, it's about that time," wheezed the weary scribe, reaching for his car keys.

"You're right!," bellowed Caray. "Waiter! Menus!"

For years thereafter, whenever Stan saw the writer, his greeting was always "Menus!"

Mikita was a prankster of the highest order, but so was Pat Stapleton. Whether the two provocateurs tested each other is unclear. It would have been like Ali vs. Frazier. But if they were off limits to one another, Keith Magnuson was their steak tartare. The young defenseman was just this side of gullible. Let's go with malleable.

Thus, the infamous snipe hunt. Mikita and Stapleton informed Magnuson that the Blackhawks would embark on a team snipe hunt one evening. They drove Magnuson out to a suburban cornfield, told him it was Wisconsin, and sent him out into the darkness with instructions to lure the birds by calling, "Here, snipe. Here, snipe." Magnuson, outfitted with a lantern and sack to collect snipe, soon found himself oddly alone.

But not for long. Local police arrived and "arrested" Magnuson because he was hunting snipe without a snipe hunting license. Magnuson was brought to a fake courtroom, then put in a jail cell. He asked the cops if he could make one phone call, to his friend Stan Mikita! One of the ringleaders! The other one, Stapleton, coincidentally showed up later with the guys and he threw out another dagger. "What happens when Billy Reay, the head coach, finds out that you've been arrested, Keith?" Magnuson's eyes rolled. Reay, naturally, was in on the gag too, waiting for his phone to ring.

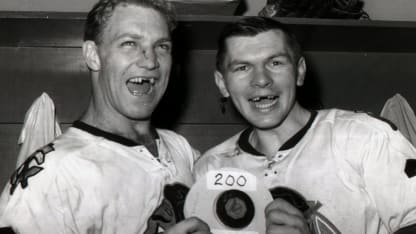

Mikita was no pushover in business. Nor was Jill. He had his contract hassles with the Blackhawks because that's the way it was back then. Management didn't have a salary cap, but management had a budget. After leading the league in scoring for two straight years, Stan fought General Manager Tommy Ivan over $500, and threatened to walk out on the eve of the opening game before signing for $12,500 in 1965.

When Hull jumped to the World Hockey Association in 1972, players had more leverage. Mikita was courted by the Chicago Cougars for serious money, but he doubted their viability, signed for a decent raise with the Blackhawks and bowed in thanks toward Hull in Winnipeg.

Long before the globalization of hockey as we now know it, Mikita was a pioneer. From hardscrabble beginnings in Czechoslovakia, he and Jill raised a wonderful family with four children. Stan, forever grateful, made random acts of kindness part of his routine, and not for photo ops.

Shortly after Magnuson and Cliff Koroll's rookie year, Mikita called them over the summer to meet for lunch. Instead, he drove them to Soldier Field for the initial Special Olympics in 1968. This is what you do, Mikita intoned, when you're a Blackhawk. Visit churches. Go to nursing homes. Give back to the community.

When Mikita became deeply involved in the American Hearing Impaired Hockey Association-he knew no other way than deeply involved-he didn't have to ask teammates to show up every day for kids who were challenged. The Blackhawks came out of respect for Mikita and a cause that meant so much to him. Stan didn't just explore or dabble in humanitarian ventures. He surrounded them.

For 22 years, Mikita was the soul of the Blackhawks. He possessed a peerless hockey IQ, along with a grasp of a well-balanced existence that resonated beyond the boards. But as Mikita's career wound down, his battle wounds mounted, as did losses by the team. Hours before Christmas Day 1976, Reay was rudely fired with a note under his office door. Bill White, Bobby Orr and Mikita-all injured-were appointed coaches, the latter two as assistants.

When White was asked about his first move as head man, he quipped, "I'm going to remove all my doors from their hinges." Mikita, usually in good humor and appreciative of such a one-liner, wanted no part of the arrangement. He thought it was a farce and felt for Reay.

The rest of Mikita's Blackhawk career was neither glorious nor appropriate. A new regime took over, and he was offered a new contract with an embarrassing 75 percent pay cut until President Bill Wirtz intervened. When Stan mothballed his skates, he did so with dignity and class. His number 21 was retired, but he deserved better. He left without a bad word for the Blackhawks, but he left feeling unwanted around them. It felt as though, as his sweater was hoisted to the ceiling, the man himself was being shown his way to Gate 3 ½ for the last time.

"'Stosh' will be deeply missed, but never, ever forgotten.”

— Chicago Blackhawks (@NHLBlackhawks) August 7, 2018

—Statement on behalf of Blackhawks Chairman Rocky Wirtz. #ForeverABlackhawk pic.twitter.com/22g99vnjnB

However, Mikita still had family, a world of friends and a fertile mind. Other endeavors beckoned, especially golf. A scratch player, he pursued that industry with typical vigor. He studied, he earned status as a professional, and he did the grunt work at a shiny new course, Kemper Lakes. He wasn't celebrity window dressing. He logged long hours in the golf shop, embraced the landscape, and gave lessons.

A lot of sports types matriculated there, not just hockey players, even that writer guy again with the story about Harry Caray. Stan offered tips, watched the typist-clerk on the range, and deduced that the poor soul couldn't transfer his practice swing to the course because he was a mental case when it mattered.

"I think I could help you become a pretty good golfer," Mikita told me with one more harpoon, "but first I'd have to cut your head off."

Stan's failing health robbed him of many moments these last few years. At the NHL's 2017 Centennial celebration in Los Angeles, he was honored in a slam dunk as one of the 100 greatest players ever. He couldn't attend, but Jill was there, along with daughter Jane Mikita Gneiser and one of her and Scott's three sons, Billy.

In April, before the Blackhawks closed their season, they staged a classy "One More Shift" tribute to Mikita. Billy, along with brothers Charlie and Tommy dashed out on the United Center rink, their pants on fire, all wearing No. 21. Beautiful. Alas, Stan couldn't be there because, as Jane said, her dad was "from the neck up, completely gone."

Stan also had to pass on the 50th anniversary of the Special Olympics at Soldier Field in July. Magnuson was totally invested after Mikita took him there in 1968, and now, Kevin Magnuson pretty much ran the show. The son also rises. Keith would have been so proud of Kevin, and so would have Stan.

After Keith perished in a tragic auto accident in December, 2003, it was Kevin, now the man of the house, who stood up at the church service and talked about his dad's first Christmas in heaven. Well, they're both up there now, Maggie and Mikita, a couple of Blackhawks poking fun at each other and laughing. One would assume Keith is safe, because Stan wouldn't dare try to pull that snipe hunt stunt again.

Or would he?