BostonBruins.com - For decades, Willie O'Ree was without one of his most prized hockey possessions. Almost 60 years after he suited up for the Bruins, he had yet to track down one of his game-worn Spoked-B sweaters.

That changed unexpectedly in January 2018.

As the Bruins and NHL celebrated the 60th anniversary of O'Ree becoming the league's first Black player, he was invited to Boston for a number of celebrations that included the dedication of a street hockey rink bearing his name and a pregame ceremony at TD Garden.

O'Ree Taking His Rightful Place in Garden Rafters

NHL's first Black player will become 12th Bruin to have his number retired

© Steve Babineau/Boston Bruins

But it was something that happened after that game between the Bruins and Montreal Canadiens that left O'Ree stunned.

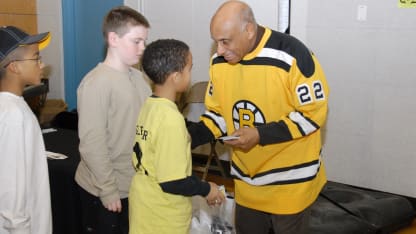

During a postgame visit to the B's dressing room, O'Ree was greeted by Boston defenseman Matt Grzelcyk and his father, John, a member of the Garden's Bull Gang for over 50 years.

It was then that John Grzelcyk presented O'Ree with one of the former Bruins' game-worn No. 22 sweaters that had been left behind at the old Boston Garden. It was passed on to the elder Grzelcyk by a Bruins equipment staffer and remained in his possession for years before he finally had the chance to present it to O'Ree.

"I wanted to wait for the right time," said Grzelcyk, "and I think this is the right time."

In January 2021, the Bruins made sure that nobody will ever have trouble finding O'Ree's No. 22 again, as the organization announced that it will be honored forever in the TD Garden rafters as the 12th number retired by the club. The ceremony was postponed one year until Jan. 18, 2022 - 64 years to the day of his NHL debut - due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

"Throughout the history of the National Hockey League, there have been very few individuals that have had such a profound impact on the league and its culture than Willie O'Ree," said Boston Bruins CEO Charlie Jacobs. "After breaking the color barrier as a Boston Bruin in 1958 and eventually retiring from professional hockey in 1979, Willie became the ultimate ambassador for improving diversity and inclusion within the game of hockey.

"The entire hockey world is forever indebted to Willie for all that he has done, and continues to do, for the sport. We are incredibly proud to retire Willie's number and cement his legacy as one of Boston's greatest athletes."

O'Ree, 85, was informed of the honor on Monday by Bruins president Cam Neely. Neely, whose No. 8 already hangs in the Garden rafters, was pleased to make the phone call, saying O'Ree's "contributions to the game of hockey transcend on-ice accomplishments and have opened countless doors for players who have come after him. He is without question deserving of this honor."

"I was sitting in my backyard," O'Ree, who lives in San Diego, said of where he was when he got the call. "I said, 'Hi Cam, how are you?' He said, 'Fine, I just have something special to tell you.' And he said, 'The Bruins are going to retire your number.' And I said, 'Oh my gosh.' I was at a loss for words there for a few seconds…I'm overwhelmed and thrilled about having my Bruins jersey hung up in the rafters."

O'Ree will join Neely, Eddie Shore (No. 2), Lionel Hitchman (No. 3), Aubrey 'Dit' Clapper (No. 5), Milt Schmidt (No. 15), Bobby Orr (No. 4), Johnny Bucyk (No. 9), Phil Esposito (No. 7), Ray Bourque (No. 77), Terry O'Reilly (No. 24), and Rick Middleton (No. 16) as the only players in Boston's almost 100-year history to have their numbers retired.

"It's wonderful, really," said O'Ree, who played with Bucyk and was coached by Schmidt. "I'm just thrilled and honored to be a part of the Bruins organization…I have the highest respect and highest admiration for the entire Bruin organization, especially the guys that I played with during that time."

An Unprecedented Journey

O'Ree cemented his place in hockey lore nearly 63 years ago, on Jan. 18, 1958, in Montreal when he suited up for the Bruins - in a 3-0 win over the Habs - and became the first Black player to participate in an NHL game. During his second stint with the Bruins in 1961, the New Brunswick native became the first Black player to score a goal in the NHL with his tally in Boston's 3-2 victory over the Canadiens on New Year's Day.

But his journey toward history started well before that in his hometown of Fredericton. The youngest of 13 children, O'Ree started skating at the age of 3 years old - using "double runners" that were clipped on to his boots - on the backyard rink that his father, Harry, built.

"I never played on an indoor rink until I was 15," said O'Ree. "I started playing and I was just obsessed."

By the time he was 17, O'Ree was good enough to advance his career and joined the Quebec Frontenacs junior team. He was guided by the advice of one of his brothers who told him that "there is no substitute for hard work" and "you only get out of something what you put into it." O'Ree lived by those words throughout his junior career and eventually turned pro in 1956 when he arrived in Quebec to play for the Aces of the Quebec Hockey League.

It was during his stint in Quebec that he suffered a catastrophic eye injury when he was struck by an errant puck. O'Ree was left blind in his right eye but kept it as quiet as he could, knowing that if anyone at the NHL level found out, his career would be finished before it even began.

"I was obsessed with playing the sport. Just that burning desire," said O'Ree. "Even when I lost my eye the second year of junior, everybody said, 'You should quit.' I said, 'Well I can still see.' I just kept on playing. We didn't wear any helmets, no face-shields and no cages back then. I forgot about being blind, I just went out and played."

O'Ree talks to media via zoom about jersey retirement

In addition to his eye injury, O'Ree also had to overcome countless racist taunts and slurs that were hurled at him at every step along the way.

Despite the hatred that he endured, O'Ree remained somewhat unaware of the magnitude of his accomplishments. As he worked his way up to the highest level of hockey with the Aces, his coach, Punch Imlach, told him that he had the skills to make it to the NHL and that if he did, he'd be making history as the league's first Black player.

"Well, it kind of went in one ear and out the other," said O'Ree.

O'Ree was focused on making it to the NHL no matter the circumstances. And he reached that goal on that January night in 1958 when the Bruins called and summoned him to Montreal for a contest against the Canadiens. Schmidt, the Bruins coach at the time, and Lynn Patrick, the team's general manager, told him that, "'we brought you up because we think you can add a little something to the team. You're a Bruin now, just go out and play your game and don't worry about anything else.'"

It wasn't until a visit to the NHL All-Star Game in 1991 - some 30-plus years after his historic debut - that O'Ree truly realized the impact that he had made on the sport.

"I got a call from the NHL inviting me to the All-Star game in Chicago. And when I picked up the phone and answered, I said, 'Well, why are you inviting me? I haven't played in 30 years,'" said O'Ree. "[The person] said, 'Well, we realize that you broke the color barrier.' My wife, [Deljeet], and I went, had a great time. That was 30 years after I left the league. Sometimes things take a little longer."

A Career to Be Proud Of

O'Ree played one more game for the Bruins in 1958, suiting up the next night, Jan. 19, for his first tilt at Boston Garden - a 6-2 loss to the Canadiens. He was returned to Quebec for the remainder of the 1957-58 campaign and spent the next two-plus seasons in the minors, splitting time in Quebec, Kingston, and Ottawa, before returning to Boston in November 1960.

O'Ree played 43 games for the Bruins that season, notching 4 goals and 10 assists, becoming the first Black player to register a point in the NHL with the only multi-point game - two assists - in Boston's 4-2 win over the Blackhawks. Two of his goals were game winners.

During that memorable 1960-61 campaign, O'Ree donned No. 22 for the first time. After wearing the No. 18 sweater for his two-game stint in 1958, O'Ree wore No. 25 for his first nine contests in 1960, before finally settling on No. 22 for the final 34 games of the season.

"Apparently, it was the one that was presented to me," O'Ree joked, adding that at the time there was no special significance to the number.

O'Ree played his last game with the Bruins - and in the NHL - on March 19, 1961, against Chicago, but went on to have a lengthy career in the Western Hockey League with the Los Angeles Blades and San Diego Gulls before retiring from the game in 1979 at the age of 43. He won two scoring titles in the WHL and potted 30 or more goals five times, including a career-high 38 in 1964-65 and 1968-69.

"I always set goals for myself," said O'Ree. "I had set a goal that I was going to play junior hockey and hopefully play pro. The 21 years I played pro, I really felt I had something to give back to the game and give back to the sport. Of the 21 years that I played, my goal was to get back into the National Hockey League in some capacity.

"I wrote letters. I was trying to get in doing some coaching and doing some community service work, doing some scouting. A door would open, a door would close, a door would open, a door would close."

His Finest Chapter

Following his hockey career, O'Ree went on to work at the Hotel Del Coronado on Coronado Island in California. But in 1998, a door opened so wide with opportunity that he couldn't pass it up.

Bryant McBride had recently been named an NHL Vice President and head of the NHL's new diversity program and was anxious to get O'Ree involved with the game again. The new initiative had a goal of growing the sport of hockey in - among other places - city schools, Boys and Girls Clubs, and juvenile detention centers.

O'Ree believed strongly in the program and accepted the role of NHL Diversity Ambassador - a position that he has now held for nearly a quarter of a century - to spread the 'Hockey Is For Everyone' message of inclusion, diversity, and dedication to thousands of youth across North America.

"I looked the program over and it was involving kids, traveling, doing on- and off-ice clinics, speaking in schools, juvenile detention facilities, Boys and Girls Clubs, YMCA's - any place there was kids that would be able to maybe take on hockey," said O'Ree. "I started and all of a sudden, things just started to move. I've been working with the NHL for 23 years now.

"So many things have happened after I retired - so many good things."

Street hockey rink unveiled in Willie O'Ree's honor

Since his retirement from hockey, O'Ree has done some of his most important and impactful work, while also receiving some of his finest recognition. In 2003, O'Ree was awarded the Lester Patrick Trophy for outstanding service to hockey in the United Sates, and in 2008, he received the Order of Canada - the nation's highest civilian honor.

In 2018, a street hockey rink was named in his honor in Boston's Allston neighborhood to commemorate the 60th anniversary of his NHL debut. A few weeks later, O'Ree was formally inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in the Builders category.

"It's well-deserved. It's just the right thing to do," Bruins captain Patrice Bergeron said of O'Ree's number retirement. "It's amazing the impact that he's had, breaking the color barrier but also his work with inclusion and diversity in hockey and pursuing that for so many years now. He's a huge ambassador and someone I got to know over the years. He's an amazing person to talk to, an amazing honor…I'm so happy for him."

Beyond the awards and recognition, however, is O'Ree's greatest legacy - all the Black players that have followed in his footsteps to reach the NHL in the decades since he broke down the wall in 1958. Yet, while so many have made it to the sport's highest peak, there remains so much work to do.

"These players are there because they have the skills and ability to be there," said O'Ree. "They're not there just because they're Black players or they're players of color. They have proven that they can play...There have been a lot of changes. There are more kids playing hockey today than ever before. There are more girls playing hockey today. The exposure is out there.

"What I wanted to try to do is expose as many boys and girls as possible and give them the opportunity to play the sport…if they come and they don't like it, they can just walk away from it. It's not going to cost them anything. But I can honestly say, the number of clinics I've conducted over the years, once I get these boys and girls on the ice, I've not had one boy or girl come up to me and say, 'Oh Mr. Ree, I don't like this, I'm not coming back.'

"I've got a good record going. It just takes sometimes the word of mouth. And then again, these boys and girls have a lot of role models that they look up to. That's a big thing, to have these players come out and just talk to these boys and girls for maybe five minutes or just to come out and have a picture taken. That means a lot to them."

What will mean even more, perhaps, is that for the rest of Bruins history, O'Ree's No. 22 will hang in the rafters to serve as a reminder and an inspiration for all of those that may question whether or not they can achieve their dreams.

"Willie O'Ree, a young Black kid that set goals for himself and stayed focused on what he wanted to do, believed in himself and wanted to play not only professional hockey, but hopefully one day play in the National Hockey League," O'Ree said when asked what his No. 22 banner will represent.

"I said that I would strive to be all that I could be. And I could probably just leave it at that."

This article was originally published on Jan. 12, 2021 upon the initial announcement of O'Ree's number retirement.

Willie O'Ree Jersey will be retired by Bruins