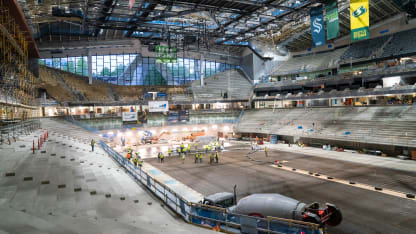

Climate Pledge Arena was abuzz with Kraken fans Friday morning. Those enthusiasts also happen to be among the 1,000-plus construction workers on the job site for Seattle's brand-new arena due to open this fall.

During their morning work breaks, dozens of workers, standing alone or socially distanced from one another, checked out the concrete pour for the arena's ice rink slab, which commenced at 4 a.m. More than 40 trucks rolled in to supply some 400 cubic yards of concrete. The concrete (experts prefer the term to "cement" and, believe me, the specialty crew in action Friday is an expert group) was filling in over the 13 miles of piping that will serve to freeze the ice surface to NHL standards.

Slab Happy

The mood at Climate Pledge Arena Friday was a mix of joy, wonder, curiosity and concrete during "big milestone" of pouring the ice rink foundation, a giant stride closer to Kraken puck drop

CPA closer to hosting Kraken games with cement pour