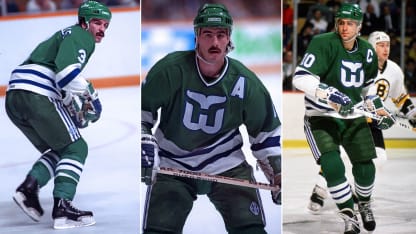

The Hartford Whalers did not experience much on-ice success during their time as an NHL franchise.

Their best season came in 1985-86, when they reached the second round of the Stanley Cup Playoffs and pushed the eventual-champion Montreal Canadiens to Game 7.

1985-86 Whalers have lasting impact in NHL coaching, management ranks

Francis, Quenneville, Tippett among those on Hartford team who were 'cerebral' students of game

It's the furthest the Whalers would ever get in the postseason before they left town in 1997 after 17 seasons and became the Carolina Hurricanes. And though the legacy of the Whalers these days is a campy goal song called "Brass Bonanza" and a whale-tail logo that appears to be more popular now than when they played, the members of the mid-1980s Whalers, specifically the 1985-86 team, have made a huge impact on the NHL that is still felt today.

That Whalers team included six future NHL coaches, two future NHL general managers, several players who went on to be assistants in the League, and another who became a prominent player agent.

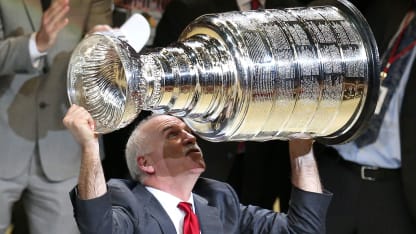

Consider that one of their defensemen was Joel Quenneville, who went on to coach the Chicago Blackhawks to three Stanley Cup championships and is the second-winningest coach in NHL history.

Their top center was Ron Francis, a Hockey Hall of Famer who would become the Hurricanes general manager and is the first GM of the NHL Seattle expansion team, which will begin play in 2021-22.

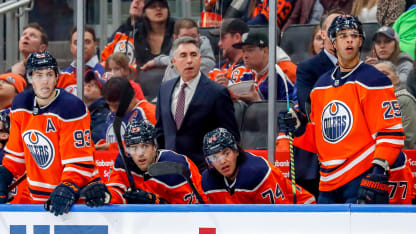

Another Whalers forward at the time was current Edmonton Oilers coach Dave Tippett, who coached the Dallas Stars and Arizona Coyotes and was a senior adviser for Seattle for about a year before being hired by Edmonton last May.

Forward Kevin Dineen coached the Florida Panthers from 2011-13, coached Canada to a gold medal in women's hockey at the 2014 Sochi Olympics and is coach of San Diego of the American Hockey League.

Forward John Anderson is a former Atlanta Thrashers coach and Wild assistant who coached the Blackhawks' AHL affiliate in Chicago for 14 seasons.

Forward Dean Evason is coach of the Minnesota Wild. Forward Paul Fenton was GM of the Wild after being assistant GM of the Nashville Predators, and is a scout for the Columbus Blue Jackets.

Forward Doug Jarvis is a senior adviser with the Vancouver Canucks after having been a longtime NHL assistant. Defenseman Brad Shaw is a Blue Jackets assistant who has also been in that role for the St. Louis Blues, Tampa Bay Lightning and New York Islanders. He coached the Islanders for the last 40 games in 2005-06.

Defenseman Ulf Samuelsson, a former assistant with the New York Rangers, Coyotes and Blackhawks, was coaching Leksands prior to the Swedish Hockey League canceling its season in March due to the coronavirus.

Goalie Steve Weeks was an assistant with the Whalers and Thrashers, and a goaltending coach with the Blackhawks.

Then there is goalie Mike Liut, who is neither a coach nor team executive but, like several of his former teammates, works with NHL players: He is managing director of Octagon Hockey agency, with clients that include forwards Mikko Rantanen of the Avalanche, Leon Draisaitl of the Oilers and Patrik Laine of the Winnipeg Jets.

"For me, as a guy who covered them back then, I saw they had a lot of cerebral players," said Chuck Kaiton, the Whalers/Hurricanes radio play-by-play voice from 1979-2018. "... All these guys had that little something that made you know that, if they wanted to stay in the game, that it would be in a coaching capacity or even in a management capacity."

For some of the former Whalers who would carve out such careers after their playing days, it all started with old-school chalkboard sessions with Hartford.

Tippett said those discussions usually involved Quenneville, Jarvis, Evason and Liut trying to figure out how to defend Quebec Nordiques forwards Marian, Peter and Anton Stastny or take away Montreal Canadiens forward Guy LaFleur's one-timer.

"We looked at that and did things, tried to figure out the game, how we were going to win," Tippett said last month on a conference call arranged by the NHL that included Quenneville. "We were kind of a small-market team, we were the underdogs, we were always looking for advantages. It was a good group, and it's amazing how many of these guys have stayed friends to this day and remember those good-old days."

It's also amazing that this many of them are still involved in the game. But why is that the case?

"I think it just came at a time when the League was expanding," said Liut, a former University of Michigan assistant. "Players were playing longer, there were more coaching opportunities, and the college and junior programs were not seen as natural feeders to pro hockey. So a little right time, right place, and the right interest.

"… There aren't that many teams (from back then) that come close to [having] that many [coaches and front-office members]. I don't know. I don't think there's a definitive answer. You're nibbling at the edges, and it's a combination of all these things."

Kaiton said players talked and thought hockey constantly.

"Jarvis definitely was a tremendous student of the game, and Joel was also," he said. "[Quenneville] would tell you himself he was a very limited player as a defenseman, but he always knew how to be in the right position and he played hard all the time. These guys were students of the game. Dave Tippett [was] the same way. He was a tremendous penalty-killer, and you have to be smart to be a good penalty-killer. But they always talked hockey off the ice. Same thing with Ronnie Francis."

Shaw made his NHL debut with the Whalers late in the 1985-86 season. He said he was struck by the way Tippett, Francis and others approached the game.

"One of the things that showed up, and I think it either helped my playing career or coaching career or both, is there was a concept that you find solutions," Shaw said. "It was a pretty brief [stay] for me back then, but it was pretty eye-opening for a guy who had spent a lot of time in the minors and watched guys kind of slug away and tried to become better in all things. What these guys did is they had figured out a way to, not specialize, but get really good in one area and create a value and create a role on a team or satisfy a role on a team."

The hockey talk was continuous, be it at the chalkboard, at dinners or on the golf course. Jarvis remembers a lot of conversations during player car pools. On days when the Whalers couldn't skate at the Hartford Civic Center, players would dress there, pile into each other's cars and head to the community rink.

"I think we looked forward to the discussions and the preparation part of it within our own team to what we were going to be possibly seeing that night," Jarvis said of the 1985-86 Whalers. "How we were going to handle whatever the strength of the team we were playing, the personnel on the team we were playing. And we really had a good year. [There were] a number of players in that group that were just so passionate about the game, that wanted to be better, better themselves in their preparation of the game, and that involved a lot of discussion with each other. I found it pretty unique to that group, and we had fun with it."

But players who have ideas they want to implement need a coach who's willing to let them do so. They had that with Jack Evans, who coached the Whalers from 1983-88. Kaiton said Evans was a mix of father figure and disciplinarian who allowed players to have a voice in what happened on the ice.

"He was like a father who has confidence in his kids," Kaiton said, "saying, 'If you embarrass the family, I'm coming down on you. And if you don't, I'm letting you be a man, be a player.' Jack was the right coach at the right time for that team. He was a kind guy and a coach who all the players respected, and I think he was probably a role model for a lot of those guys."

Dineen said he wasn't part of the chalkboard sessions -- "They basically told me, 'Go in front of the net, stay there, take your beating and let everyone else do everything around the outside'" -- but said players appreciated Evans giving them the chance to bring ideas to the table.

"With Jack it was very simple," Dineen said. "Our drills didn't change much. We had a good idea what practice would look like and there were some different areas in the game that you'd get a group of guys who think the game and say, 'Hey, let's try different things.' John Anderson, who coached the [Chicago] Wolves for a good 10 years at least, would've been on the power-play side of things. [Tippett] would've been a guy who would've really focused on the penalty kill as well as Joel."

Tippett and Quenneville have been the two most successful NHL coaches among former Whalers.

Quenneville has a record of 925-558-145 with 77 ties with the Blues, Colorado Avalanche, Blackhawks and Florida Panthers, and is second in wins behind Scotty Bowman (1,244). The current Panthers coach won the Jack Adams Award as NHL coach of the year with the Blues in 2000 and guided the Blackhawks to the Cup in 2010, 2013 and 2015.

Tippett is 590-438-129 with 28 ties with the Stars, Coyotes and Oilers. He guided the Stars to the Western Conference Final in 2008, won the Jack Adams Award with the Coyotes in 2010 and coached Arizona to the Pacific Division title and conference final in 2012.

Tippett's former teammates said they knew he would be a coach even then.

"At the time their first daughter was born, they had a finished basement, it was her playroom," said Liut, who lived next door to Tippett for six seasons in Hartford. "But he built a makeshift bookshelf in a corner that cordoned off a desk. I used to call it Dave's fort. Like when you're a little kid, you build a fort. He would go there, and it was all VHS [tapes], but he would study film, in essence, and watch what guys were doing, and teams were doing."

Evason said that on bus rides after games, "I would sit with Tippett and it would be just like analyzing the game and breaking down what we did on forecheck and on the PK and we've got to better on the PP. He was just very in-depth about that at that early age."

Tippett led Hartford's penalty kill, and in his six full seasons with the Whalers (1984-85 to 1989-90), their unit was in the NHL's top six four times. They had the League's best penalty kill in 1987-88 (84.3 percent).

"We had a PK unit with you and [Jarvis] on it that was specializing," Quenneville said to Tippett on the call last month. "You knew exactly what to take away. Your approach was a little different than a lot of the guys that I'd been around, and you could see you had that next ingredient, not just the way you competed, you were relentless, but you really did study the game, not just play the game. And I think that's what helps with where you're at today."

As for Quenneville, he said on the call that "for sure, the last guy that anybody would have thought would be a coach would've been me."

Tippett said he disagreed. Other former teammates said it wouldn't have been shocking if Quenneville became a coach, but he just seemed to have other interests. Quenneville was always a numbers guy; while playing in Hartford he got his series 7 license, a requirement for an entry-level stockbroker, and worked in financial management for a few years in the offseason.

"But you know what? Joel is dumb like a fox," said Dineen, who was an assistant under Quenneville in Chicago from 2014-18. "He may have played that role that he wasn't going to stay in hockey, but there was this natural feel for how the game should be played and playing the right way, and you can see kind of the background that they (Quenneville and Tippett) came from, that they both survived as players and thrived as players by being quality on the defensive side of things. And I think their teams reflect that now, and always have, wherever they coached."

Quenneville wasn't known for being fast in his playing days -- during the video call, he joked about how slow he was -- but he defended well.

"He wasn't a very good pivoter, a very good backward-to-forward skater," Shaw said of Quenneville. "So if someone was coming down with speed on the wing, a lot of times they would get around him. But he had such a good stick that they wouldn't get a shot on net. So he kind of blows up the whole idea of a 1-on-1, you have to get good body position and this and that. And at the end of the day, all you need to do is get the job done. That's what a lot of these guys had figured out."

Quenneville, Tippett and Shaw each transitioned to coaching as a player/assistant. Quenneville signed for that role under coach Marc Crawford with St. John's of the AHL in 1991-92 and rejoined Crawford as an assistant with the Nordiques/Avalanche from 1994-97. Tippett was player/assistant for Houston of the International Hockey League in 1994-95 and was named coach midway through 1995-96. Shaw was a player/assistant under former NHL coach Rick Dudley with Detroit of the IHL from 1995-97.

Most of them didn't think about going behind the bench or into the front office until later in their playing careers. But Dineen always figured he would coach because it was in his blood. His father, Bill, coached the Philadelphia Flyers for two seasons (1991-92, 1992-93) with Kevin on the team, won two World Hockey Association championships as coach of Houston (1974, 1975) and coached Adirondack of the AHL to two Calder Cup championships (1986, 1989).

"When you grow up around that kind of atmosphere, you're around the game on a daily basis," Kevin Dineen said. "It's a heck of a way to get brought up, and you can look at how many guys whose kids have followed through in the game. For me, playing as long as I did (19 NHL seasons), I think there was a natural feel to try to find what you could do to stay in the game."

Jarvis said he always wanted to stay in hockey too.

"I really enjoyed watching the game," said Jarvis, who, upon retiring as a player, became an assistant with the Minnesota North Stars/Dallas Stars from 1989-2003. He's also been assistant with the Canucks, Canadiens and Boston Bruins. "I enjoyed watching what other teams were doing and the kind of systems we were using. It was just something that I felt I would like to do if I had the chance to be able to do it."

The Whalers were a close-knit group who made hockey their focal point on and off the ice. A lot of players from those teams keep in touch. Considering how many of them are still involved in hockey, it's easy for them to do so.

"It's amazing, the bond we all had at the time, and now you're seeing, it's almost every building we go to, every rink, there's somebody from the Whale," Quenneville said. "There's someone that bumps into you who was with the Whale, in every single capacity in the game. And there's a lot of good stories too. The Whale still lives everywhere you go."

NHL.com staff writer Tom Gulitti contributed to this story