WOONSOCKET, R.I. --It takes a keen eye to see everything, to take in the pucks tucked in the corners, the citations hung from the sides of the display case, the framed photos stacked two and three deep. The trophies are crowded on each other, the letters sit overlapped with plaques and pictures, the glass awards and bowls and cups and keys and medals fill every inch of a space that cannot contain the legacy it tries to hold.

There is the puck from Brian Lawton's first NHL goal. There is a letter from NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman. There is the key to the city of Woonsocket. There is a jersey with the No. 696 on it, commemorating a national record for wins that has long since been smashed. Next to it is a jersey with No. 800 on it, just as obsolete.

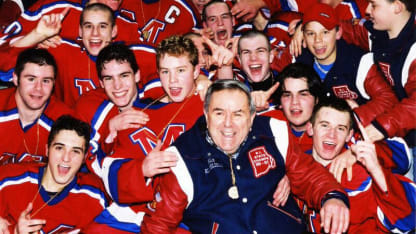

Bill Belisle impacted lives of many NHL greats

Legendary Rhode Island prep coach to be inducted into U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame on Wednesday

It is dizzying, realizing what all this symbolizes, what all this means: This is a hockey life, these mementos of a hockey lifer, a man who still stands proudly behind the bench of Mount Saint Charles Academy, a private Catholic school of about 850 students from sixth to 12th grade, in this French-Canadian pocket of Rhode Island, even as he celebrated his 87th birthday in September.

The door to the arena's office swings open, revealing an equally cluttered, equally packed room, though here it is different. It is not just hockey memorabilia. Here there are family photographs mixed in, New York Yankees hats alongside more plaques and trophies and pucks and pictures of celebration and devastation. Not that there is much of the latter.

In mid-November, the players returned to Bill Belisle for his 42nd season as coach at Mount Saint Charles, which Belisle has led to 990 wins, to a run of 26 consecutive state titles, to 32 state titles overall, and to a place among the greats in the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame, where he will be inducted on Nov. 30 in a class that includes the championship United States team from the 1996 World Cup and Craig Janney.

Which all leads to the reaction by New York Islanders general manager and former Mount Saint Charles goaltender Garth Snow upon hearing the news: "What took so long?"

\\\\

Dave Belisle's eyes darted around the room. Every player had raised his hand, quickly, immediately, without hesitation. There were two holdouts. Dave was one. His brother John was the other.

Brother John Hebert, the Mount Saint Charles principal at the time, called a meeting with the hockey players returning to the team for the 1975-76 season, including the Belisle brothers. The question? Should Bill Belisle, then an assistant coach, be made the head coach to try to turn around a sagging program?

This was not what the brothers wanted. They knew what would result. But seeing that every one of his teammates had his hand raised, Dave put his up, suddenly panicked that his lack of support would get back to his father. John held his ground.

"We knew, my brother and I, we were in trouble, our lazy rear ends," said Dave Belisle, who has coached alongside his father at Mount Saint Charles since 1981. "We just said, 'Oh, we cannot have my father as coach.'"

They knew, too, as they later admitted when Brother Hebert asked, that this was the best thing for the program, the right thing to do.

They knew this would change what Mount Saint Charles hockey was and would be. And it did. Quickly.

Two seasons later, when Dave Belisle was a senior, the team lost its final game, in the state championship. It would not lose that final game again for a very, very long time.

From 1977-78 to 2002-03, Mount Saint Charles, and Bill Belisle, were the best in Rhode Island.

"Twenty-six in a row after that he won," Dave Belisle said. "So for a long time I was the last captain to ever lose a championship game at Mount Saint Charles."

\\\\

Bill Belisle groomed players. Of the first three United States-born players selected No. 1 in the NHL Draft, two came out of Mount Saint Charles: Lawton in 1983 and Bryan Berard in 1995. That's two of the seven American players who have been drafted with the No. 1 pick. Belisle also produced Mathieu Schneider, Brian Boucher, Keith Carney, Paul Guay, Jeff Jillson and Snow.

Bill Belisle won games: His winning percentage is .818 during those 41 years, a record of 990-183-37.

But even with all the wins, all the success, all the NHL players, that was never really what it was about for Belisle. It was the point, and not the point, all at once.

"I always like to say about Bill that I think he developed men," said Schneider, a former NHL defenseman, current NHL Players' Association executive, and 2015 inductee to the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame.

"It wasn't necessarily about hockey. That was a vehicle. … We rarely lost games, but it wasn't about the wins and losses to Bill. It was really about accountability, from one period to the next, one shift to the next."

That might best be summed up in what Bill Belisle said to his team in the moment that crushed them all, when Mount Saint Charles lost the state title in 2003-04 to Toll Gate High School. The moment of devastation had finally come, after 26 years.

As Dave Belisle recalled to his father, "I remember you coming in and one of the first things you said was, 'This, my boys, is one of the proudest moments of my whole life, of my coaching career.' You said that. 'Because you guys gave everything you had, and that's all I asked.'"

That was the moment when all of what Belisle taught them mattered most, when what he accomplished in raising them from boys to men was most poignant. The loss stung. The tears flowed. But, ultimately, he accomplished what he set out to do.

Because that one loss didn't really matter. Not then, not now.

"What he has done for hockey in the state of Rhode Island and all of New England is second to none," said Toronto Maple Leafs general manager Lou Lamoriello, who recruited many of Belisle's players while the coach at Providence College. "He's an icon in Rhode Island, in high school hockey.

"There was nothing he didn't do: He drove the Zamboni, he cleaned out the lockers, he sharpened skates. He did it all. I have tremendous respect and admiration for him."

Everybody involved with hockey in Rhode Island shares that respect for Bill Belisle.

It was evident as far back as 1983, not that long into his coaching career, when other Rhode Island teams rallied around the coach in his darkest hour, after a near-fatal skull fracture sustained during a Mount Saint Charles practice left him in a coma.

They sent cards. They held moments of silence. They believed.

He came back the next season and has not left since.

\\\\

Bill Belisle laughed and admitted the truth: It wasn't all respect and admiration.

"For four years they hated me," Belisle said. "I wouldn't play for myself. That's how bad I was."

For the players, the butterflies started in sixth or seventh period of the school day. The nerves crept in, with the knowledge practice was approaching. It would be intense. It was always intense. This was what it meant to play for Belisle.

"I dreaded -- I mean, I dreaded -- walking down those steps from school to the arena," Boucher said. "Look, he would kick you off the ice. If he didn't like what he saw, he would tell you to go home and shower and get out of here and kick you flat off the ice.

"So, he's right, I think a lot of kids did hate his guts, but I can tell you he got the very best out of a lot of kids."

There are gales of laughter as the stories are told, the twinkle implanted firmly in the eye of Belisle, though the dichotomy is jarring between this kindly gentleman and the dictator being described by his son.

There was the snowball fight by his players that resulted in an afternoon of sprinting in the snow for an hour and a half, followed by two hours of ice time Belisle forced Woonsocket High School to give up to him. There was the dine-and-dash incident that led to the players not being allowed to dress in the locker room for a week. There was the time he sat his best player, David Capuano, brother of Islanders coach Jack Capuano and a future NHL player, in the 1986 state championship game for lack of effort.

Then there was the rule about watching practice.

In the years when Lawton was on the team, as he recalled, there was only ever a single guest at practice: Bobby Orr.

Dave Belisle recalls one parent, a mother, who had to use the bathroom so badly -- the only women's room in the arena is located next to the ice surface -- that she crawled along the floor to get there, so she wouldn't raise the wrath of the coach. It didn't work. (OK, he said, but hurry up.)

But the best story, the truest test of the will of Bill Belisle, was when Minnesota North Stars scout Al "Smokey" Cerrone brought a special guest to practice, one who flew in from Minnesota specifically to take a look at Lawton, before the North Stars made a decision on who they would select with the No. 1 pick in 1983.

The doors to the ice surface squeaked when opened, the better for Belisle to hear any intruders. This time, after he heard that squeak, he skated furiously to the near end of the ice, wanting to see who broke a sacred rule, who tried to enter his space.

"He says, 'Can I help you?'" recalled Dave Belisle, who was on the ice at the time. "He says, 'Smokey, you know my rule.' 'But Bill, he flew all the way in from Minnesota.' 'Smokey, you know my rule. … You guys have got to get out of here. You know the rules. I don't give a [darn] who he's here to see.'"

The special guest, by the way, was Lou Nanne, the general manager of the North Stars.

Belisle didn't care. He kicked him out, told him to come back on Friday at 9 o'clock, told him to watch Lawton in the games like everyone else. He was running a practice, and outsiders didn't belong, no matter who they were there to see or scout or draft No. 1.

\\\\

All of this is a monument to the living game, the pucks and shots and skates that can be heard beyond the closed doors of the rink, those doors whose creakiness is part of the legend. These are the sounds of a game that has touched Bill Belisle and which he, in turn, has touched.

Things have changed through the years. He no longer skates, having given that up six or seven or eight years ago. The chain-link fence that encircled the ice surface at Brother Adelard Ice Arena was finally replaced, just this summer, with glass.

Time advances, but Bill Belisle stays, perhaps softened, perhaps not. Though he has given in to the advancing years in some ways, the echoing voice is still there, the yell belonging to a man in his prime hollering at players in theirs. It carries, bringing with it the message he has imparted to so many: the teachings, the caring, the discipline. The love.

This is his life. This is his second family. This is what he has wrought.

"I spent six years of my life there, and it was by far six of the best years of my life," Lawton said. "Because of him."

They all looked up to the program, all aspired to be part of it. There was an allure there, a pull, a draw. They watched those games at 9 o'clock, watched the players who went on to greatness, saw themselves in the Montreal Canadiens-style jerseys The Mount made famous, heard the coach bellowing.

They wanted that.

"You have to understand that my initial goal playing hockey, really my sole goal, was to play varsity hockey at Mount Saint Charles, long before I ever thought about playing in the National Hockey League," Boucher said. "They had this mystique about them."

Bill Belisle made it into a program that mattered: For its wins, yes, and for the players it produced. But it mattered much more for what it did for those players.

The coach has impacted a generation of Rhode Island hockey players, and now a second generation, with players like Snow, who brings his sons to Belisle's hockey camp every summer.

Dave Belisle wonders if his dad will impact a third generation. It's clear he will, from the words of his acolytes, from the way his messages have seeped into their actions, their teachings, their lives.

That was why, when Lamoriello heard the news Belisle would be inducted, "I actually got the chills because I don't know of anybody more qualified for it. He's dedicated his life to his family and to United States hockey and to be recognized, there's no one more deserving."

This is what he has done, beyond the state championships, beyond the wins, beyond the clutter and the cups and the citations. This is a legacy.

"There will be times when I'm communicating with a player and it doesn't matter what level, whether it's a 10-year-old kid or a 30-year-old NHL player and I think back," Snow said. "I go, 'That's what Coach Belisle would have done.'"