MONTREAL -- Twenty-four.

It is a symbolic number in Montreal for two reasons: It is the number of Stanley Cup championships the Montreal Canadiens have won in their 107-year history that predates the NHL, and it is also the number of years since they last won the Cup in 1993.

Montreal spotlight can be positive, negative

Current, former Canadiens players, coaches discuss pressure of performing in 'hockey heaven'

© Francois Lacasse/Getty Images

By

Arpon Basu @ArponBasu / LNH.com Senior Managing Editor

It is also appropriate because 24 represents how many hours per day the average Montreal resident thinks about when a 25th Stanley Cup banner will hang in the rafters of Bell Centre.

That might be an exaggeration, but only a slight one, and it's part of what makes Montreal a very unique place to play professional hockey.

When he was the Canadiens' general manager after a Hall of Fame playing career in Montreal,

Bob Gainey

once described that uniqueness, that certain je ne sais quoi about playing here, as "spice."

It would become a catch-all term for Gainey to refer to any sort of controversy or hysteria that surrounded the Canadiens and impacted his ability to do his job or that of his players to do theirs.

That "spice" is not easily defined, nor is it the same for everyone, but it flavors everything in Montreal. Too much can be overwhelming, there is never too little and the perfect amount can be euphoric.

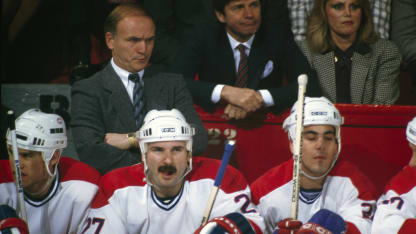

© B Bennett/Getty Images

"I think the Canadian cities, in my view, are a lot the same, but Montreal does have its own flavor because of the dual languages and the history of the team," Gainey said eight years later when asked what he meant by "spice." "Montreal fans are intense and they want the team to do well. I guess what I mean is that every day is a little more intense than it might be in Pittsburgh or Nashville.

"You really want to be the person that enjoys that, that enjoys the competition under scrutiny. If you don't enjoy the competition under scrutiny, you can deal with it for a while, but eventually it wears you out."

However, when people begin to get worn out, they can forget what playing for the Canadiens means to so many people.

After defenseman Jordie Benn was traded by the Dallas Stars to the Canadiens on Feb. 27, he called Montreal "hockey heaven" over and over. For someone like goaltender Carey Price, who has played in Montreal for his 10 NHL seasons, it can be a reminder of what makes Montreal special.

"I can't really point it out, it's just a hockey buzz about the town," Price said. "It's the only game in town, I think that has a lot to do with it. Hockey's a big part of the culture in Montreal, it always has been."

© Minas Panagiotakis/Getty Images

A perfect example of that came this month when the Canadiens practiced before traveling to face the New York Rangers. There were hundreds of kids, out of school for March break, watching at the Canadiens' suburban facility.

"It's kind of a strange way to put it, but I feel like you're in more of a show, I guess," Price said that day. "You're always on. For instance today, we had a lot of people up there watching practice and it's just a 30-minute, travel-day skate.

"But I don't even notice it anymore."

Benn certainly did, just as he had noticed it in his first game playing in front of 21,288 fans when the Canadiens defeated the Columbus Blue Jackets 1-0 at Bell Centre on Feb. 28. It was the 529th consecutive sellout there since Jan. 8, 2004 (including playoffs).

"It was everything and more than I expected," Benn, a native of Victoria, British Columbia, said of his first game. "Just to put on that jersey is a big honor. It's something a kid dreams about when he's younger. Obviously I was a [Vancouver] Canucks fan, but to come to Canada and play in Montreal and play in the Bell Centre, it was awesome.

"Dallas is its own animal, the fans there are amazing. But when you're in hockey heaven in Montreal, when the fans are cheering 'Go Habs Go,' it gets the boys going on the bench. It's pretty crazy."

Playing for the Canadiens still means something to a lot of players, and that is a major part of the spice. It's not only about the pressure, it is about being a part of something bigger than they are.

"To wear that jersey is an honor," Nashville Predators defenseman P.K. Subban said at Bell Centre on March 1, a day before his first game against his former team. "There's no ice in the building right now, it's covered up, but you don't have to see the ice to know what this building means. You just look up in the rafters and see the names and the jerseys. That's what it's about. That's why we play the game; it's for the history and we want to be a part of that history. And we are a part of it."

But with that honor comes scrutiny, the other side of the spice, and it is normally focused on three people in particular, three positions with the Canadiens that are more pressure-packed than perhaps any other in hockey. In no particular order, the people in Montreal who need to be most tolerant of the spice are the coach, the captain and the goalie.

The coach

Michel Therrien estimates he met with the media about 250 times per season while he was the Canadiens coach. This was just another one of those times.

He agreed to meet with NHL.com during the 2017 Honda NHL All-Star Weekend in Los Angeles on Jan. 28 and was in great spirits. It was his first time coaching at the NHL All-Star Game, his Canadiens firmly ensconced in first place in the Atlantic Division with a seven-point lead.

A little over two weeks later, after six losses in eight games coming out of the All-Star break but with Montreal still leading the division by six points,

Therrien would be fired

. But over the course of that 15-minute conversation, Therrien provided a window into what it is like to coach the Canadiens, and he had no complaints.

A year earlier, Therrien was at the helm of a ship that sank in historic fashion, with the Canadiens falling from the best record in the NHL to right out of the Stanley Cup Playoff race after Price was lost for the season to a knee injury sustained Nov. 25, 2015.

© Mark Blinch/Getty Images

Therrien was not unanimously adored before 2015-16, but the heat on him increased considerably during that season.

During the five seasons of Therrien's second stint as Canadiens coach (he also coached them from 2000-03), that and the period immediately preceding his dismissal were the only real difficult times he experienced. But they provide context for what he said about dealing with the public in Montreal while coaching the Canadiens.

"In Quebec we have the best fans," Therrien said. "But I think I meet with the media 250 times a year, on average. People see us in their living rooms every day, so it creates a relationship. People identify with the coach. When I meet them in the street, it's as if they are already my friends, right away. They feel like they know me as a friend.

"But the people are incredible. I have never, ever, come across a situation that was unpleasant. It's never happened. But when it's not going quite as well, I have a tendency to stay home more often than not. I don't read the papers or watch the news. Last year, I watched a lot of Netflix."

With that, Therrien laughed because he understood all too well that it came with the job. Being coach of the Canadiens means being a master of media relations as well, and Therrien played that game better than most.

In the past, when the Canadiens had a large number of Francophone players, the coach was not the sole voice speaking to French-speaking fans, who make up the majority of Montreal supporters, in their own language. But that is no longer the case.

When the Canadiens traded center David Desharnais to the Edmonton Oilers for defenseman Brandon Davidson on Feb. 28, it left center Phillip Danault as the only Montreal player with French as his mother tongue. Forwards Torrey Mitchell and Paul Byron are able to conduct interviews in French, but the days when a large percentage of Canadiens players spoke the language are long gone.

The last Canadiens team to win the Stanley Cup, in 1993, had 14 Francophone players, so times most certainly have changed. In that context, the coach becomes the face of the team, which means deftly navigating the media waters depending on how well or poorly things around the team are going.

Therrien had mastered it, often steering postgame press conferences in the direction he preferred regardless of the questions he was asked.

© Francois Lacasse/Getty Images

"What's important in my relationship with the media, what I've come to understand, is that the question isn't important," Therrien said. "What's important is my answer. So for the guy sitting in his living room, and you want me to talk about a certain subject, when he watches the news at night all you see is my answer. That's why the question, I respect it and I try to answer it the best I can, but if it's going toward an angle that I don't really want to go to, I'll try to deviate it in another direction."

A hockey coach is generally hired because, well, he knows a lot about how a team should play hockey. Media relations is a small part of the job. That's not the case in Montreal. It is a vital job requirement, as is the ability to speak both French and English so that the coach can communicate directly to the fans.

"I don't know how it is in Toronto, but Montreal is a unique market," Therrien said. "It's Francophone and Anglophone. There's a lot of passion. You can't forget that Quebecers have Latin blood, there's a lot of emotion there."

That duality within Canadiens fans, and how differently each side of the linguistic divide views the team and its decisions, is central to the unique nature of Montreal as a hockey city, as Therrien found out.

"My first time coaching the Canadiens I had

Jose Theodore

, who was starting his career, and I had Jeff Hackett as the established goalie," Therrien said. "When I played Jeff Hackett (who was from Ontario), the Francophone media screamed at me that it wasn't the right decision, that I should play the kid from Quebec. And when I played Jose Theodore, I got the same from the other side. That's how it was then. They were two different markets then, and they're two different markets now.

"This is why Montreal is a unique market. And honestly, I love coaching in this market."

On Feb. 14, Therrien was replaced by Claude Julien, who was fired by the Boston Bruins a week earlier and who had also replaced Therrien in Montreal in 2003. Julien, a Franco-Ontarian, understands fully what Therrien had mastered because, like Therrien, he has gone through it before. And he loves it as well.

"People just love their team, they're passionate about it, and those are the types of places some of us coaches love to be," Julien said the day after he was hired. "We want to be somewhere, even though there's obviously more pressure, we thrive on that. We don't see it as pressure; we see it as a challenge and we like working in those environments. I think it's exciting, I think it's fun. Maybe it's not for everybody, but obviously it's something I enjoy."

© Minas Panagiotakis/Getty Images

But not everyone enjoys it, and that's what makes coaching in Montreal so difficult for some. Jacques Lemaire would fall into that category.

Lemaire saw the constant media glare as a hindrance to his job, which is why he enjoyed coaching the New Jersey Devils and Minnesota Wild far better, with the degree of scrutiny much lower. Lemaire, a Hall of Famer, was a Canadiens forward for 12 seasons (1967-79), so he knew the environment. Still, he had difficulty managing it during his 97 regular-season games coaching Montreal, the final 17 of the 1983-84 season and the entirety of 1984-85. Lemaire relinquished the job after that season to work in the Canadiens front office until he began coaching the Devils in 1993, winning the Stanley Cup in 1995 in his second season in New Jersey.

"It's a little different playing and coaching [in Montreal]," Lemaire said. "Playing, you have the people that will talk about your game every day. You have people that after the game, you're going to go out with your wife to a restaurant, and people will come in and talk to you about the game, how they saw it and how it can be better and all of this. And it's every game. It's like your fans are with you during the day. You meet people everywhere you go and they know about the game, they know how you played the night before.

"As a coach, it's different. It's the press that does it. The press will come in and say, 'You should have played this guy more,' and it hurts because you feel like you never do the right thing. If you live with that every day it's kind of hard. You want to sit a guy and you're going to have a comment that he shouldn't sit that guy. It's not that [the media] put their opinion there, it's not that. It's what that can create with the player, with the team. Because if they're saying I made a bad move because I sat one player, then what do you think the player thinks? And you have to fight this."

Lemaire coached 15 seasons for the Devils, Wild and Devils again, but 97 games were enough for him in Montreal.

© Denis Brodeur/Getty Images

The captain

Chris Chelios

had just come off representing the United States in the 1984 Sarajevo Olympics when he arrived in Montreal, not knowing at the time he would become the first United States-born captain of the Canadiens five years later.

He immediately found out what it meant to play in Montreal.

"I had never been to Montreal before I played there, so I came in there and watched a couple of games because I was injured, and the first game I went to they were booing

Larry Robinson

because there was a bad pass, so [they were] very knowledgeable fans," Chelios said. "I felt the pressure initially. I got off to a really rough start actually because I felt the pressure. I'd never done that as a player. It never bothered me. Luckily we had a good little playoff run, my first playoffs after 12 [regular-season] games, got a little confidence and overcame that pressure."

Handling that pressure is an essential component of playing in Montreal, especially as captain, and that's what makes Gainey uniquely placed to label it "spice"; he was captain for eight seasons and later served as coach and general manager.

© B Bennett/Getty Images

Though some of the pressure comes from external sources such as the fans and media, the majority of it is rooted in the Canadiens' successful history and the constant reminders of it.

There are 24 Stanley Cup banners hanging over your head every time you play a home game, not to mention the numbers of 17 Hall of Fame players. Many of those legends routinely come to games and chat with you, encouraging you to give everything that night.

The captain bears the brunt of that. He was the one who regularly received the Stanley Cup first during the Canadiens' heyday, and is the one forced to answer for their shortcomings when they don't win the Cup, which has been the case for 24 years.

No one comes up to you and tells you that you're expected to carry on that tradition of excellence, and accept the torch and hold it high, to paraphrase the line from John McCrae's World War I poem "In Flanders Fields" that is written on the walls of the Canadiens' dressing room.

But it is understood.

"I think a lot of what feeds Montreal is the success, the history and wanting to get back to the top," said Brian Gionta, who played in Montreal from 2009-14 and was the second U.S.-born captain in Canadiens history. "Whether that's coming from inside or outside the room, those expectations are always on you.

"You feel it in the history. You're [part of the] Original Six, [the] most storied franchise in the League. When you put on that jersey you have that honor of representing that team and the area. It's nothing said. It's just kind of felt once you put on that jersey."

© Bruce Bennett/Getty Images

It is what makes the pressure of playing here different from that of Toronto, where the Maple Leafs have a history that is nearly as long as the Canadiens' and a media contingent that is perhaps even larger than Montreal's, but without the sustained winning.

Vincent Damphousse

began his career in Toronto and became a star there, but it was during a lean time for the Maple Leafs, from 1986-91. He arrived in his hometown of Montreal for 1992-93, won the Stanley Cup his first season here and was named captain in 1996, the last Francophone to hold that distinction for the Canadiens.

Few players can better describe the difference between the pressure in Montreal and Toronto than Damphousse.

"In Toronto the expectations were always a bit lower," he said. "The team hadn't won since 1967, and I was born in 1967. So it's different because the expectations are much higher in Montreal because of the number of championships they've won and that's what everyone expects, even if it might not be realistic in today's hockey.

"But I always saw pressure as a good thing. You look at the greatest athletes of all time, the ones who had the most success, and they all elevated their play when the pressure was at its highest. I'm not at their level, but that's why I loved playing in Montreal."

The Canadiens not only have a storied history, that history is literally walking around in the hallways of Bell Centre.

Jean Beliveau

, before his health prevented him from doing so, was a fixture in Section 102, Row EE, Seat 1 at nearly every game for years. At the Canadiens' first home game after his death on Dec. 2, 2014, Beliveau's seat was upholstered with his No. 4 jersey on the back and kept empty, with a spotlight shining on it throughout the game and his wife, Elise, sitting in Seat 2 as she always did.

© Francois Lacasse/Getty Images

It was the ultimate example of how the Canadiens' past can influence their present.

Beliveau was not the only alumnus to attend games, just the most visible and prominent. Montreal has a lounge reserved for its former players at Bell Centre, not far from the Canadiens dressing room, and seeing legends like Guy Lafleur or Yvan Cournoyer strolling in prior to a game is commonplace.

It could be considered a burden for the current players to constantly come in contact with such greatness, a reminder of a standard that is almost impossible to reach, but Damphousse did not see it that way.

"I saw it much more as motivation than as a burden," he said. "It helped me to see them around the team. It was a reminder that I couldn't slack off, I had to perform."

Max Pacioretty, the current captain and third United States-born player to fill the role, is the latest to carry the weight of the longest Stanley Cup drought in Canadiens history on his shoulders.

"I think a lot of times individual success is based off team success, and I know last year was my first year being captain and we kind of fell right on our faces," Pacioretty said this season. "As a player I feel like I can be judged on that, and that's fair given that I should be the leader of this team, and maybe that carried over to a part of this year."

That is how Pacioretty sees being captain, and it perfectly illustrates the inherent pressure of that role in Montreal against the backdrop of those Stanley Cup banners.

But he also says he wouldn't trade it for anything.

"I love playing here so much, and the fact I'm able to be the captain here, it sounds cheesy, but what's better in life right now?" he said. "I've got a family, I've got an awesome team, I'm the captain of the best franchise in the world."

The goalie

Theodore had a different perspective of his goalie battle with Hackett than Therrien, but felt pressure for the same linguistic and cultural reasons cited by his former coach.

Theodore, a native of suburban Laval, Quebec, was a 22-year-old hometown boy fighting to ascend to perhaps the most pressure-packed position in all of sports in 1998, with Hackett in his way.

While Therrien was defending his goaltending decisions to the Francophone and Anglophone media, Theodore was the one receiving the support from the French press. That can have its own pitfalls.

"As a player you have to play well. There's no way around it," said Theodore, who was surrounded by hype after playing 16 regular-season games and two playoff games for the Canadiens in 1996-97. "But if you're from Montreal or you're French Canadian, maybe you get too much attention too quickly. I got it after 16 games in the NHL, which might have been too quick. The same thing happened to a lot of other guys who came to training camp with some talent like Mike Ribeiro, Guillaume Latendresse, a few other guys.

© Denis Brodeur/Getty Images

"After that, once I was established, I felt I was judged on my performances so it was back to normal. But at first, yeah, it is more pressure on you. But for me it was a good pressure. It reminded me I needed to be at my best every game."

Theodore said the fact that

Patrick Roy

and

Martin Brodeur

, two Quebec-born goalies he looked up to as a kid, had already accomplished so much at such a young age normalized the environment for him. In 2002, at age 25, Theodore won the Hart Trophy as the NHL's most valuable player and the Vezina Trophy as the League's best goaltender. But by 2006, Theodore's play had slipped a bit and, with Price on the horizon, he was traded to the Colorado Avalanche -- just as Roy was a little more than 10 years earlier.

Theodore's rise to glory was very similar to Price's. The difference was that the early expectations heaped on Price were not based on the language he spoke, but rather the Canadiens' selecting him at No. 5 in the 2005 NHL Draft, his gold medal with Canada at the 2007 World Junior Championship and his 2007 Calder Cup championship with Hamilton of the American Hockey League before he got to Montreal.

Price was handed the starting job in Montreal two years after Theodore departed, when Gainey traded Cristobal Huet to the Washington Capitals on Feb. 26, 2008, eliminating the goalie competition. At the time, Gainey said it was important that Price begin learning everything that came with playing goalie in Montreal as early as possible. That way, he reasoned, Price would begin his career in earnest at an appropriate age and have plenty of experience.

Price began his career on a stark upward trajectory, but eventually lost the starting job to Jaroslav Halak for the 2010 playoffs.

By the age of 22, Price had experienced the highs and lows that come with the position in Montreal, giving him ample time to bounce back, just as Gainey had predicted. When Halak was traded to the St. Louis Blues following the 2010 playoffs, Price took back the starting job and never relinquished it, winning the Hart and Vezina trophies in 2015 at age 27.

© Andre Ringuette/Getty Images

Another big difference between Price's experience and Theodore's is the media environment. In separate interviews, Price, Pacioretty and Therrien each mentioned how social media has intensified the landscape in Montreal in a way previous generations never had to deal with. Controversies become more sensationalized, and seemingly everyone carries a high-definition camera in his or her pocket at all times.

Players need to be more careful in public today than ever before, not only in Montreal but all over the NHL and throughout professional sports in general. But the Canadiens are the only major professional sports team in their city, so attention is intensely focused on them.

"I kind of came in during an era when social media first started coming in, and that whole aspect of it has totally changed things," Price said. "There's things that go on in the city that went under the radar beforehand. Points of view weren't so widely broadcast. So I think those avenues of venting for fans weren't there previously."

As someone who came through the Canadiens system, this is all Price has known. He has shown an ability to thrive in this environment because, ultimately, it pushes players to succeed.

"When you go to the rink it's great to have a full building, it's nice to have that motivation of people rooting for you all the time," Price said. "There's other aspects of it where you just want to go to a park with your kid and just be a regular guy and be a regular dad. That's a little bit of a different aspect.

"But you have a lot of people involved, there's a lot of people rooting for you, so you can feel that when you succeed."

After he was traded, Theodore played parts of eight seasons with the Avalanche, Capitals, Minnesota Wild and Florida Panthers, and all along, he said, he yearned to find that buzz he felt playing in Montreal. Though he said the pressure came a bit too early in his career, it was something Theodore found he needed once he left.

"My best advice to anyone is to enjoy the moment because you won't play in Montreal until you're 50 years old," Theodore said. "You've got to be built a certain way to play in Montreal, and if you're built that way it means you want that pressure, so then Montreal is perfect for you. It pushes you to surpass yourself.

"When I played in Florida and even in Denver, which is a great hockey town, sometimes I found it harder. In Montreal it's almost like you play in the NFL because every game has a buzz around it. So when you play somewhere else and you need that pressure, it's almost harder to get up for games.

"So yes, there's more pressure in Montreal, but I needed that pressure to perform. I honestly believe I would not have become the same goalie I was if I started my career anywhere but Montreal."

Price has said the same about himself, most notably at the 2014 Sochi Olympics. Price had never been on such a big stage, either internationally or in the Stanley Cup Playoffs, but he calmly led Canada to gold, accustomed to the type of pressure he felt each game from his experience in Montreal.

And that, in the end, might be the "spice" of Montreal as a hockey city. Perhaps it is a built-in mechanism meant to ensure that only the mentally toughest, the fiercest competitors, the hungriest of the hungry manage to thrive here.

It hasn't produced results of late, but the overall track record is on display every game in the Bell Centre rafters, where those 24 white banners hang, waiting eagerly for one more to join them.

Robinson, a Hall of Fame defenseman who played 17 seasons with the Canadiens from 1972-89, summed it up best.

"I think what made Montreal special," he said, "was it either made you or broke you."