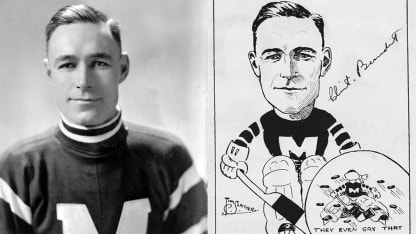

Benedict, a brilliant talent with his hometown Ottawa Senators, then the Maroons, didn't win the Vezina Trophy in his three final NHL seasons, the trophy having been donated to the league in 1926-27 by Canadiens co-owners Joseph Cattarinich, Louis Letourneau and Leo Dandurand.

Inexplicable is the fact that Benedict wasn't inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame until 1965, 11 years before his death at age 84 and years after many early-era goaltenders with lesser credentials had been enshrined.

Maybe it's because Benedict's Senators and Maroons largely faded from public consciousness when they folded in the 1930s, slipping him through the cracks.

But Benedict had every reason to be in the Hall, both for numbers that stacked up impressively beside, and even dwarfed, those of the legendary Vezina and everyone else of the day, and for his role in shaping the life of goaltenders.

Born Sept. 26, 1892, Benedict played 443 games during an 18-season career spanning the National Hockey Association and NHL from 1912-30, with a record of 243-169-29, a 2.69 goals-against average and 61 shutouts. In 28 Stanley Cup Playoff games with the Senators and Maroons from 1919-28, he was 11-12-5 with a GAA of 1.86 and nine shutouts. His teams won the Cup in 1921, 1923 and 1926.

In 17 seasons, from 1910-26, Vezina played 328 games with the NHA/NHL Canadiens, finishing with a 175-146-6 record, a 3.45 GAA and 15 shutouts. The native of Chicoutimi, Quebec, had a 10-3 record in 13 Stanley Cup Playoff games from 1918-25, finishing with a 2.569 GAA and two shutouts. He won the Stanley Cup with the Canadiens in 1924.

Vezina is viewed in a more historic light than any of the goalies who played in pro hockey's formative years, pioneers who included Benedict, Percy LeSueur, Alec Connell, Roy Worters, Chuck Gardiner, Lorne Chabot, George Hainsworth and Paddy Moran.

Benedict and Vezina went head to head for eight NHL seasons; Benedict led or tied for the league lead in games played and shutouts seven times; five times, he had the most wins and lowest goals-against average.

Hard numbers don't begin to tell his story, however. Where Vezina played a conventional stand-up style that left his pads dry at game's end, Benedict was more like the Dominik Hasek of his time, flopping in his crease like a fish out of water.

Every modern-day goaltender owes a huge debt to Benedict, whose dropping to the ice bullied the new-born NHL to introduce a rule in 1918 allowing a goaltender to leave his skates, a practice that had been illegal in the NHA. Indeed, he had been nicknamed "Praying Benny" by sarcastic Toronto fans for his habit of falling to his knees, allegedly to thank the Lord during a scramble or after a save.