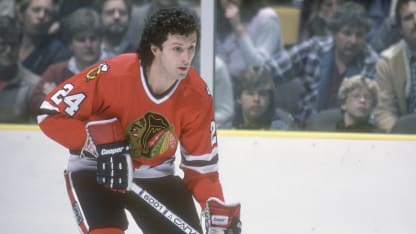

Doug Wilson

wasn't bothered by having to wait until his 24th year of eligibility to be voted into the Hockey Hall of Fame. So having the induction ceremony postponed for a year because of the coronavirus pandemic wasn't a big deal either.

Wilson entrance into Hockey Hall of Fame worth the wait

Norris Trophy-winning defenseman with Blackhawks, current Sharks GM voted in during 24th year of eligibility

© Focus On Sport/Getty Images

Wilson's big day finally arrived Monday, when he was inducted into the Hall of Fame along with

Jarome Iginla

,

Marian Hossa

,

Kevin Lowe

, Kim St-Pierre and Ken Holland.

"It was just such a privilege to play in this league, and for something like this to happen was beyond my wildest dreams," Wilson said. "I just look at it as I was so fortunate to play in this league and with the guys that I did and have the experiences that I did. That's just how I viewed the game and my journey."

Wilson, general manager of the San Jose Sharks since 2003, didn't have a direct journey to the Hall of Fame following 16 seasons in the NHL with the Chicago Blackhawks and the Sharks. Known for his booming shot, crisp outlet passes and intelligence (and for being among the last to play in the NHL without a helmet before he retired in 1993), Wilson is 12th in NHL history among defensemen with 237 goals, 15th with 827 points and 18th with 590 assists in 1,024 regular-season games.

Wilson, who played 14 seasons for the Blackhawks holds their records for goals (225), assists (554) and points (779) by a defenseman. He topped 60 points in a season seven times, including an NHL career-high 85 points (39 goals, 46 assists) in 76 games in 1981-82 when he won the Norris Trophy voted as the best defenseman in the League.

Iginla, Hossa lead 2020 Hockey Hall of Fame Class

His 39 goals that season remain the fourth-most by a defenseman in NHL history, behind Paul Coffey with 48 in 1985-86 and 40 in 1983-84, and Bobby Orr with 46 in 1974-75.

"I was on the team when 'Willie' scored 39 goals," said Calgary Flames coach Darryl Sutter, a forward with Chicago for eight seasons. "I remember going to the front of the net and knowing where he was going to shoot it. He had an outstanding hockey IQ. He saw the game and read the game.

"If you put him in today's game the way the game is played now, you see the numbers he put up then, he'd put up even bigger numbers now."

There was more to Wilson's game than offense though. His ability to read the ice helped him defensively too.

"He obviously had great vision," longtime defense partner Bob Murray said. "He could see not only offensively on the power play, but we killed penalties too. He just was an all-around great player. There were no holes in his game."

Sutter noted Wilson played before the tracking of ice time, but he usually logged heavy minutes, often against the opponent's top line.

"I would bet that's a player that would play in the high 20s," Sutter said. "Even if you did it now with even strength, this guy played even-strength minutes against everybody's best players. So he had to be a pretty good player."

Wilson was voted an NHL First Team All-Star in 1981-82 and a Second Team All-Star in 1984-85 and 1989-90. He was selected to play in the NHL All-Star Game seven times, including in 1992 as the expansion Sharks' first representative.

© Graig Abel/Getty Images

But he was overshadowed for much of a career that overlapped with Coffey, a three-time Norris Trophy winner, and five-time Norris winner Ray Bourque.

Coffey and the Edmonton Oilers, who won the Stanley Cup five times in seven seasons from 1984-1990, were a frequent obstacle for Wilson and Chicago. The Blackhawks finished first in their division seven times and reached the Campbell Conference Final five times during Wilson's 14 seasons, but couldn't advance, losing to the Oilers in 1983, 1985 and 1990, the Vancouver Canucks in 1982 and the Flames in 1989.

"Paul Coffey obviously was one of the greatest ever and we played the Oilers many times," said Blackhawks teammate Denis Savard, a 2000 Hall of Fame inductee. "[Wayne Gretzky] was there and [Mark Messier] was there, and you look on the defensive part of the game with Coffey on their side and 'Willie' being on our side and I don't think there was much difference.

"If Paul Coffey would've played with us, he would have had a great career and if 'Willie' would've played with them, he would have a great career plus a couple championships. I believe that."

Murray believes not having a Stanley Cup championship on his resume might have impacted Wilson's Hall of Fame candidacy, along with his humility. Despite his offensive production, Wilson wasn't the flashiest player.

"He was obviously a great player, but he didn't demand the attention as others do, and that hurt him a little bit in not getting [to the Hall of Fame] so quickly," Murray said. "That and the fact that all those years we were really good in Chicago, unfortunately there was a team that was much better than us in Edmonton and we just couldn't beat them."

Growing up in Ottawa, Wilson had an in-house role model in his older brother, Murray Wilson, a forward who won the Stanley Cup four times (1973, 1976-78) during his six seasons with the Montreal Canadiens before playing one season with the Los Angeles Kings and retiring in 1979. Wilson followed his brother's footsteps by playing three seasons of junior hockey for Ottawa in the Ontario Major Junior Hockey League under legendary coach Brian Kilrea, who was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame as a Builder in 2003.

After being selected by Chicago with the No. 6 pick in the 1977 NHL Draft, Wilson scored 34 points (14 goals, 20 assists) in 77 regular-season games as a 20-year-old rookie in 1977-78. As a young offensive defenseman, Wilson looked up to Orr, an eight-time Norris Trophy winner with the Boston Bruins, and then got to be his teammate with the Blackhawks for six games in 1978-79 before injuries forced Orr to retire.

Wilson's other early influences with Chicago included defenseman Keith Magnuson, center Stan Mikita and goalie Tony Esposito.

"You look at the incredible Bobby Orr and how he changed the game, and watching the Montreal Canadiens a little bit from the inside of it from my brother's view was pretty special, what a great organization that was," Wilson said. "Then obviously who I got to play with in Chicago, the Mikitas, the Magnusons, the Espositos. … It was just about life and their wisdom and experiences, the fact that they would share that with me and, obviously, just how special our greatest players in the game are because of how they carry themselves."

Wilson tried to carry himself in the same manner. After Esposito retired in 1984, Wilson and his wife, Kathy, took over from the Espositos as the host for many of the team-related family activities away from the rink.

Wilson did similar after being traded to the Sharks on Sept. 6, 1991 and being named their first captain. Although San Jose didn't win many games during Wilson's two seasons playing there (17-58-5 in 1991-92 and 11-71-2 in 1992-93), he was integral in establishing the culture.

"It was team first. Really cared about his teammates," said Minnesota Wild coach Dean Evason, a forward with the Sharks their first two seasons. "With the expansion situation in San Jose, we were a bunch of a misfits from all over the place. It wasn't like the expansion of today where you're getting pretty high-end players. So for us to have any kind of success, Doug knew that we had to be a really close-knit group.

"Although we did not have a whole lot of success the first couple of years, we were a real close group because of his leadership qualities, for sure."

Wilson never expected to go on to become Sharks GM, but being part of the organization from the start gives him an appreciation for how far it was come.

"We were all in it together," Wilson said. "We had an amazing owner, Mr. George Gund, with his love for the game and the love for the community. We represented that team and everybody on that team, the Kelly Kisios, the Dean Evasons, the Rob Zettlers, Perry Berezan, the Mike Sullivans. It was a group of people that I think really understood to give back, connect with the fans, work hard and compete hard.

"We might not have had all the talent in the world, but I think to be there and grow the game, that relationship with the fan base was a credit to the whole group."

© Dave Sandford/Getty Images

Wilson also credits his wife, Kathy. After Wilson agreed to waive the no-trade clause in his contract to be moved to the Sharks, a lot fell on her to settle their family, including daughters Lacey and Chelsea and sons Doug and Charlie, in San Jose.

"The kids were so young and my wife's pioneer spirit was amazing," Wilson said. "I had a team to join, and she was coming to a new place she had never been to and her spirit to do that was incredible."

So when Hockey Hall of Fame chairman Lanny McDonald called with the news that he'd been voted in by the selection committee, Wilson wanted Kathy to be on the phone with him.

"I wanted her to hear it because without her it doesn't happen," Wilson said.

Wilson suggested that the Hall of Fame call coming in his 24th year of eligibility might have been destiny. He wore No. 24 throughout his NHL career.

"It's funny," he said. "I think I got the call on June 24 too."

If Wilson has any disappointment about the induction ceremony being delayed a year, it's that it prevented Esposito from attending. He died Aug. 10 from pancreatic cancer.

Wilson had the chance to thank Esposito over the phone, though. Mikita died in 2018, so Wilson also called his family express his gratitude.

"I've had chances to thank a lot of people and that's the one thing that this time has allowed," Wilson said. "There's a lot of people that were there at key points in my life, but also I was able to share what people meant to me. … That's what spurs the emotions, just the people that were there during the journey in life."