As part of the NHL's Centennial Celebration, longtime hockey reporter and analyst Stan Fischler, "The Hockey Maven," will write a biweekly scrapbook for NHL.com. The scrapbook will look at some of the strange-but-true moments from the NHL's first 100 years.

There is no Superman, alias The Man of Steel, in the NHL. In fact, there's never been anyone on skates close to being quite like the comic book superhero/Hollywood character of the same name.

Eddie Shore's miracle midnight ride

Hall of Fame defenseman made superhuman effort to get to game

By

Stan Fischler

Special to NHL.com

But there have been NHL players capable of superhuman feats, and up near the top of the list is Eddie Shore. If any performer in the League's 100-year history epitomized the furious drive and spirit of hockey players, it was Shore.

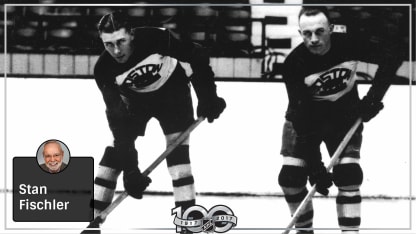

Regarded by many as one of the finest defensemen in history, the former wheat farmer from the Edmonton area developed into one of the NHL's biggest stars and drawing cards soon after joining the Boston Bruins in 1926.

For 10 years no other player in the League generated the excitement that Shore did. Although Shore was not an especially large man by today's standards (5-foot-11, 190 pounds), he more than made up for whatever he may have lacked in size by the wild, almost reckless passion with which he played.

An offbeat episode during the 1928-29 season symbolized why the man nicknamed "The Edmonton Express," was such a fantastic performer. This turbulent tale took place when the NHL was into its second decade. Specifically, it began when the Bruins prepared for an away game with the mighty Montreal Maroons at the Forum.

To get there, the Bruins had to take an overnight train from North Station, where all but one of the players arrived for the trip. Boston general manager Art Ross had a firm rule that if any of his players missed the train, he would be fined $500.

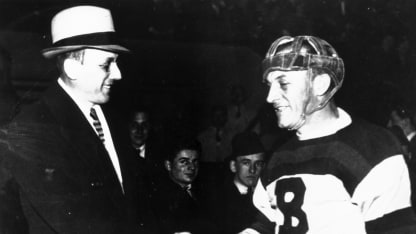

Alas, Shore did miss that train because of extenuating circumstances that became even more extenuating thereafter. In an interview I did with Eddie at Madison Square Garden the afternoon he won the Lester Patrick Trophy in 1970, he explained to me in detail the roots of his midnight saga.

It all began on the night of Jan. 2, 1929. As the Pullman carrying the Bruins slowly rolled away from the platform, Ross walked through the sleeping car, counting his players. When Art reached the last berth he realized that one of them, Shore, was missing.

"Mr. Ross didn't know it," Shore told me, "but I was running down the station platform trying to jump on the last car of the train. I didn't make it and had just missed the train because my taxi had been tied up in a traffic accident coming across town."

Shore was determined to reach Montreal in time for the game, especially since his Bruins already were shorthanded because of injuries. He also was well aware of the $500 fine Ross levied against any player who missed a road-trip train.

The first thing Shore did was to check the train schedule. No luck; the next express wouldn't reach Montreal until after game time. He tried the airlines and was told all plane service had been canceled because of a sleet storm. He then decided to rent an automobile but changed his mind when a wealthy friend offered him his limousine and a chauffeur.

At 11:30 p.m., Shore and the chauffeur headed north on a 350-mile trip over icy, snow-blocked New England mountains. It was sleeting and there were no paved superhighways, no road patrols, no sanders.

The chauffeur drove through the storm at three miles an hour. "I was not happy at the rate he was traveling," Shore remembered, "and I told him so. He apologized and said he didn't have chains and didn't like driving in the winter. The poor fellow urged me to turn back to Boston."

At that point the car skidded to the lip of a ditch. Shore took over the wheel and drove to an all-night service station, where he had tire chains put on. By then the storm had thickened into a blizzard. Snow caked either side of the lone windshield wiper and within minutes the wiper blade froze solid to the glass. "I couldn't see out the window," Shore said, "so I removed the top half of the windshield, which you could do on cars in those days."

His face was exposed to the blasts of the icy wind and snow, but he still managed to see the road. At about 5 a.m., in the mountains of New Hampshire, "we began losing traction. The tire chains had worn out."

Slowly, Shore eased the car around a bend in the road where he could see the lights of a construction camp flickering. He awakened a gas station attendant there, installed a new set of chains and weaved on. "We skidded off the road four times," he said, "but each time we managed to get the car back on the highway again."

The second pair of chains fell off at three in the afternoon. This time Shore stopped the car and ordered the chauffeur to take the wheel. "I felt that a short nap would put me in good shape," he recalled. "All I asked of the driver was that he go at least 12 miles an hour and stay in the middle of the road."

But the moment Shore dozed off, the chauffeur lost control of the big car and it crashed into a deep ditch. Neither Shore nor the chauffeur nor the car had any damage, so Shore hiked a mile to a farmhouse for help.

"I paid $8 for a team of horses," Shore said, "harnessed the horses and pulled the car out of the ditch. We weren't too far from Montreal, and I thought we'd make it in time if I could keep the car on the road."

He did. At 5:30 p.m., Shore drove up to the Windsor Hotel, the Bruins' headquarters and, ironically, the same place where the NHL originally was founded. He staggered into the lobby and nearly collapsed.

"He was in no condition for hockey," Ross said. "His eyes were bloodshot, his face frostbitten and wind-burned, his fingers bent and set like claws after gripping the steering wheel so long. And he couldn't walk straight. I figure his legs were almost paralyzed from hitting the brake and clutch."

Nevertheless, Shore ate a steak dinner, his first real meal in 24 hours, and refused the coach's orders to go to sleep. "I was tired all right," Shore asserted, "but I thought a 20- or 30-minute nap would be enough, then I'd be set to play."

© B Bennett/Getty Images

Teammates Dit Clapper and Cooney Weiland entered Shore's room an hour later and shook him gently. Nothing happened. They rolled him over the bed and onto the floor. Still nothing happened. Weiland filled several glasses with water and poured them over Shore's face. This time he woke up and immediately insisted on playing.

Ross nixed that idea.

"I knew how durable he was," he insisted, "but there's a limit to human endurance. I finally decided to let him get on the ice, but at the first sign of weakness or sleepwalking I'd send him to the dressing room. I had to worry about him being groggy. What if he got hit hard and wound up badly hurt?"

The game was rough and fast. The powerful Maroons penetrated Boston's zone often, but Shore always helped repulse them. Once he smashed Hooley Smith to the ice with a vicious body check and drew the game's first penalty. Ross considered benching him at this point but changed his mind.

When the penalty time had elapsed, Shore jumped on to the ice and appeared stronger than ever. Shortly before the halfway point of the second period he skated behind his net to retrieve the puck. He faked one Montreal player, picked up speed at center ice and swerved to the left when he reached the Maroons' blue line, He sped around the last defensemen and shot.

"I would say I was 15 feet out to the left," he said. "I can remember exactly how my shot went. It was low, about six inches off the ice, and went hard into the right corner of the net."

The time of the goal was 8:20 of the second period. The Bruins led 1-0.

Shore still showed no signs of his ordeal during the third period (he had another two-minute penalty) and almost 24 hours after he chased the train down the North Station platform the final buzzer sounded. He played the entire game (minus the four minutes in penalties) without relief and, what's more, had scored the only goal of the game.

© B Bennett/Getty Images

Ross never fined him for missing the train.

The incredible feat took place before the cartoon version of Superman appeared in Action Comics. By that time, Eddie Shore had gone a long way toward proving that he was the super man on ice!