Everybody was there. Well, almost everybody, as it turns out. On the night in Ottawa when he changed hockey history, Lord Stanley himself, the governor general of Canada, notably was absent. But he certainly made his presence felt.

The Ottawa Hockey Club executives were there. So were nearly all of the players, and a great many of their most dedicated fans. So was the press that covered the games. Depending on which newspaper accounts were most accurate, there were at least 70 people there, and perhaps more than 200, including guests from out of town.

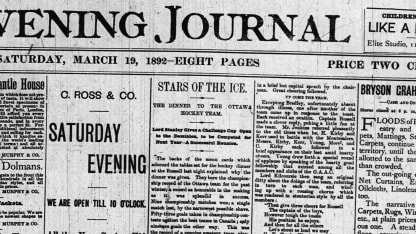

The night Stanley Cup was born

Idea for trophy unveiled 125 years ago in Ottawa

By

Eric Zweig / Special to NHL.com

John H. Moss of the rival Osgoode Hall Hockey Club and J.A. Laurie, secretary of the Ontario Hockey Association, had made the 250-mile trip from Toronto by train. J.C. Walsh of the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association and C.A. McCarthy of the Ottawa College team had much shorter trips. John Garvin of the Toronto News was there as well, but it was a short trip for him because he was not actually a sports reporter but a member of the Parliamentary Press Gallery. Unfortunately, no one was able to make it there on behalf of another key ice rival, the Quebec Hockey Club, which at least had the good manners to send a telegram. It was read aloud by J.W. McRae, president of the Ottawa Amateur Athletic Club, which was hosting the evening's festivities.

"Quebec regrets that she cannot send a delegate and do honor to the finest hockey team in Canada," the letter read.

And just who was the finest hockey team in Canada? Why the Ottawa Hockey Club, of course. For though the Ottawa club lacked the final victory that would have put this claim beyond dispute, nobody who followed hockey in 1892 -- and certainly no one who was at the banquet at the Russell House Hotel on March 18 -- would have argued that they hadn't been the sport's best team that season.

But what if the matter of determining hockey's best team didn't have to be subject to opinion? Before the evening at Russell House was over, the hockey officials and guests who had gathered would hear of Lord Stanley's concept to determine a yearly champion. From that night on, hockey never would be the same.

\\\\

The banquet at Russell House honoring the Ottawa Hockey Club on the evening of March 18, 1892, was typical of a well-to-do bash for the late Victorian era. The men dressed for dinner in formal attire, eating course after course of fine food, washed down with plenty of brandy and other liquors. A number of women joined them for dessert, but they likely had been cleared from the room when J.W. McRae called the company to order at about 10 p.m.

The fun then began with a toast to Queen Victoria and other items of state business before McRae proposed a toast to the health of the Ottawa Hockey Club. Their many friends in attendance drank to them while standing on their chairs. Then, one by one, the triumphant players were called upon to make speeches. More toasts and speeches followed late into the night.

Among the last performances of the evening was a song composed especially for the occasion by Lord Kilcoursie, aide-de-camp of Lord Stanley and a teammate of Stanley's sons, Arthur and Algernon (known to the family as Algy), on the Rideau Rebels hockey club. Kilcoursie's song had a verse for each member of the Ottawa Hockey Club and the doings of the team. It concluded with a tribute to captain Bert Russell before everyone joined Kilcoursie in a rousing rendition of the chorus:

"Then give three cheers for Russell/The captain of the boys/However tough the tussle/His position he enjoys/And then for all the others/Let's shout as loud we may/O-T-T-A-W-A."

After a few more songs, everyone joined in singing the Canadian national anthem and "Auld Lang Syne" before the gathering finally dispersed after midnight. Kilcoursie's song was a popular addition to the evening's entertainment, but it was far from the biggest contribution he made that night.

This had been the first meeting of its kind for the Ottawa Amateur Athletic Club, but Russell House was no stranger to such get-togethers. Since Canada became a country in 1867, the hotel had become the home away from home for many of the parliamentarians of the Senate and the House of Commons when they gathered in Ottawa. "The conferences that took place in its halls and rooms," the Montreal Gazette said in 1925, "resulted in many transactions of national importance and some that brought about far-reaching effects, commercial as well was political." The effects of the banquet for the Ottawa Hockey Club could not be labeled commercial or political, but they certainly would be far-reaching.

Philip Dansken Ross was among those at Russell House that night. Because he no longer was serving in the top position at the Ottawa Amateur Athletic Club, he did not have the spot of honor at the head table that then-president McRae enjoyed that evening. Still, as president of the Ottawa Hockey Club and publisher of The Ottawa Journal, Ross had done more than most to raise the profile of the team to one that was worthy of such a reception. He likely also was most responsible for the announcement that would make the evening so significant.

The Ottawa Amateur Athletic Club had won its second straight Ontario Hockey Association title in 1892, but that had involved playing two games, each won handily. Its true target had been the championship of the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada. Toward that end, Ottawa had won six games of the seven it played during the 1892 AHAC season. No other team had won more than once, but because of the league's complicated challenge system -- with no set schedule and only the winner of each week's lone game guaranteed to play again the following week -- Ottawa could not claim the league title because it lost its final game. The championship instead went to the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association, which had lost to Ottawa in January and February but defeated it in the season finale March 7.

Despite the disappointing end to the season, Ottawa hockey fans were more than happy with their team's accomplishments and treated the players like champions, feeling that they deserved to be. It didn't seem right that Ottawa had lost the title under the system in place, and Ross had a pretty good idea of who could fix it.

On the night of the hockey banquet at Russell House, just after the toast to Queen Victoria, Ross had the honor of asking those present to raise their glasses and drink to the health of the governor general, who, Ross said, "had shown himself a hearty friend of all healthy athletics, and particularly of hockey."

\\\\

Frederick Arthur Stanley was known to Canadians as Lord Stanley of Preston, the 1st Baron Stanley of Preston and, eventually, the 16th Earl of Derby. (He did not assume the latter title until April 1893, when his older brother, Edward, the 15th Earl, died and he returned to England two months before his term of office was due to end in September.) He became the sixth governor general of Canada in 1888. The son of a three-time prime minister of Great Britain, Stanley was a member of Parliament from 1865-1886. He also sat in the House of Lords and served a short stint as the secretary of state for the British colonies. Lord Salisbury, the British prime minister who was acting on the advice of Queen Victoria, offered Lord Stanley the position of governor general Feb. 1, 1888. He accepted the post May 1 and sailed from Liverpool 30 days later. After arriving in Quebec City on June 9, Stanley and his wife, Lady Constance, proceeded by special train to Ottawa, where he was sworn into office.

Like most British aristocrats of the day, Lord Stanley was an avid sportsman. He and his large family (the Stanleys had seven sons and one daughter, but also had lost a boy and a girl in infancy) were enthralled by the sports they discovered during the posting to Ottawa. Hockey became a particular favorite among the Stanley boys and of daughter Isobel; son Arthur Stanley had proposed the creation of the Ontario Hockey Association in 1890.

There were cheers throughout the banquet hall in Russell House when Ross offered his toast to Lord Stanley, and though Stanley was the one notable absence that evening, Lord Kilcoursie rose in his stead to offer the governor general's thanks and to read a special letter Stanley had prepared for that evening:

"I have for some time been thinking that it would be a good thing if there were a challenge cup which should be held from year to year by the champion hockey team in the Dominion of Canada.

"There does not appear to be any such outward and visible sign of championship at present, and considering the general interest which the matches now elicit, and the importance of having the game played fairly and under rules generally recognized, I am willing to give a cup which shall be held from year to year by the winning team.

"I am not quite certain that the present regulations governing the arrangement of matches give entire satisfaction, and it would be worth considering whether they could not be arranged so that each team would play once at home and once at the place where their opponents hail from."

"The reading of the letter was greeted with enthusiastic applause," The Ottawa Journal said. Lord Stanley's offer was accepted and a decorative silver punch bowl, created in Sheffield, England, was purchased in London for 10 guineas. (This price often is said to be the equivalent of $48.67, but that would be the exchange rate on 10 pounds. Guineas had a slightly higher value, making the price closer to $51.) The bowl was engraved with the name "Dominion Hockey Challenge Cup," but was known from the beginning as the Stanley Cup.

The Cup was presented for the first time in 1893 to the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association for winning the championship of the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada. It would be available for challenges from the champions of the Ontario Hockey Association, and soon from the champions of any recognized provincial league throughout Canada. When Canadian teams began to pay for players in the fall of 1906, the Stanley Cup became a professional trophy, and when the National Hockey Association (forerunner of the NHL) and the Pacific Coast Hockey Association emerged as the dominant professional leagues by the 1913-14 season, the challenge era ended in favor of a "World Series of Hockey" format, which continued after the NHL began play in 1917-18.

The PCHA expanded into the United States in 1914-15, and U.S.-based teams became eligible for what had been a Canadian-only trophy. Top professional hockey out west collapsed in 1926, and only NHL teams have competed for the Stanley Cup since the 1926-27 season.

And it all began 125 years ago, when guests at a grand affair in Ottawa learned of what would become the Stanley Cup, a trophy worthy of a glitzy celebration in itself.