Growing up, Willie O'Ree had two dreams: to play professional hockey and to play in the National Hockey League. Never mind that no black player had ever competed in the NHL or that O'Ree lost nearly all sight in his right eye while playing junior hockey. O'Ree's mind was made up.

O'Ree become the NHL's first black player in early 1958 when he was called up to the Boston Bruins. He played two NHL games that season, then another 43 with Boston during the 1960-61 season. In 1980, O'Ree retired after a 21-year professional hockey career. Whether consciously or not, O'Ree began to dream again, thinking of ways to get back into hockey. "I was gonna get back to the NHL," O'Ree said in the compelling new ESPN documentary "Willie."

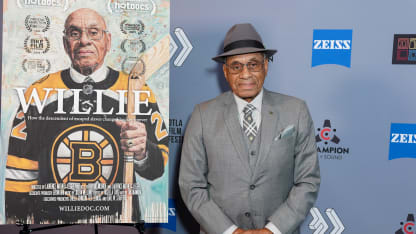

Dreaming On

More than 60 years ago, Willie O'Ree was the first black player in the NHL, and at 83, he is still imagining a more diverse sport