In two weeks, the NHL will pause its schedule for the 4 Nations Face-off. This nine-day tournament – from February 12 through February 20 – will feature NHL players from four countries – two in North America (the United States and Canada) and two from Europe (Sweden and Finland).

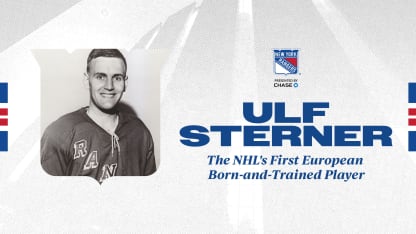

Six decades ago, a 23-year-old from Sweden became the first player who was born and trained in Europe to skate in an NHL game, paving the way for more Europeans to make their mark in the NHL in the years that followed. And he did so in a Rangers uniform on Madison Square Garden ice.

Ulf Sterner was accustomed to playing on a big stage for several years prior to wearing a Blueshirts sweater. A native of Deje, Sweden (outside of Gothenburg), Sterner played in Sweden’s top league for several seasons as a teenager and represented his country in the 1960 Winter Olympics shortly after his 19th birthday.

But it was Sterner’s performance in another tournament – the 1962 IIHF World Championship – that first put him on a course to play professionally in North America. Sterner tallied 16 points in seven games during the tournament – which took place in Colorado Springs – while helping Sweden win a gold medal; in addition, he was named to the tournament All-Star Team.

After that tournament, Sterner was put on the radar of Rangers’ General Manager Muzz Patrick by two people. One was Jackie McLeod, who played parts of five seasons with the Rangers and played against Sterner in the 1962 IIHF World Championship. The other was sports journalist Ulf Jansson, who wrote for the Swedish newspaper Idrottsbladet. With their recommendation, Patrick placed Sterner on the Rangers’ “negotiation list”, allowing the organization the opportunity to sign him to a contract if he wanted to play in North America.

Sterner stayed in Sweden for the 1962-63 season, playing with Frolunda (the same organization that Henrik Lundqvist would play for four decades later). The season was a successful one for the forward, as he won the Guldpucken (top player of the year in Sweden) and helped Sweden win a silver medal at the 1963 IIHF World Championship.

In August of 1963, Sterner decided that he was ready to try and play in North America, as he decided to report to the Rangers’ Training Camp in Winnipeg prior to the 1963-64 season.

“The Maple Leafs and Bruins were also high on him, but we put him on our negotiation list first,” Patrick told reporters on the day Sterner agreed to report to the Rangers’ Training Camp. “We’re delighted that Sterner has agreed to come … and he has a good chance to make the team. He has been the best European player the past couple of years.”

Sterner arrived in Winnipeg with Jansson – who served as his translator – and attempted to get acclimated to the NHL style of play during the Rangers’ Training Camp. At 6-foot-2, the center would have been one of the tallest players in the league at the time, but he did not have the experience of playing in a league that had checking like the NHL had. In addition, Sterner did not want to jeopardize the amateur status he still held, as he wanted the opportunity to represent Sweden at the 1964 Winter Olympics.

Before the preseason had ended, the Rangers and Sterner agreed that he would play no more than five NHL games, allowing him to play in the Olympics. He was expected to make his NHL debut in the Rangers’ home opener on October 16, 1963 against the Red Wings. Sterner, however, did not make his NHL debut in that game; while Patrick received verbal permission that Sterner would not jeopardize his amateur status by playing in five NHL games, the Rangers never received written confirmation that this would be the case.

Sterner elected not to play until that confirmation was received. The following day, the ruling was delivered that he would be ineligible to play in the Olympics if he played for the Rangers beforehand. As a result, his NHL debut was delayed, and he returned to Sweden to prepare for the Olympics.

After helping Sweden earn a silver medal in the 1964 Olympics, Sterner returned to North America for the Rangers’ Training Camp prior to the 1964-65 season. He ultimately began the season with the team’s affiliate in the Central Professional Hockey League, the St. Paul Rangers. After a brief stint in St. Paul, Sterner joined the Blueshirts’ American Hockey League affiliate, the Baltimore Clippers, where he quickly became one of the team’s most dynamic offensive players.

Emile Francis – who replaced Patrick as the Rangers’ General Manager in October of 1964 – told reporters that Sterner, “showed himself to be one of the finest passers in the game at both St. Paul and Baltimore.” Red Sullivan – the Rangers’ Head Coach in 1964-65, who previously played center in the NHL and was the Blueshirts’ captain during his playing career – said that, “(Sterner) has one of the best backhand shots I’ve ever seen.”

Finally, late in January of 1965 – with several players out of the lineup due to injury – Sterner was recalled by the Rangers. He made his NHL debut on January 27, 1965 against the Boston Bruins at MSG, becoming the first player who was born and trained in Europe to play in an NHL game.

Rangers fans at MSG gave Sterner a standing ovation when it was announced that he would be in the lineup, and he was cheered by The Garden Faithful throughout the contest. Although he didn’t tally a point in the contest, he looked as though he belonged, as he skated alongside two of the team’s top wingers – Don Marshall and Bob Nevin. Sullivan told reporters that Sterner played a “fine game”, while Sterner said that he was “very happy” with the contest.

Sterner’s next games with the Blueshirts, however, did not go as well as his debut. As the Rangers played back-to-back contests against the Canadiens and Red Wings, Sterner was checked at every opportunity by the toughest players on both teams, and he was on the receiving end of an elbow from Montreal’s John Ferguson. By the end of his third NHL game, Sterner was sporting two black eyes.

Following Sterner’s fourth NHL game – which took place on February 3, 1965 against the Chicago Black Hawks – the Rangers and Chicago made a seven-player trade that included the Blueshirts’ captain, Camille Henry. The Rangers had to make room on the roster to accommodate the players they were acquiring from Chicago, and as a result, Sterner was loaned back to Baltimore.

He would not play in the NHL again. Sterner completed the 1964-65 season with the Clippers, and at year’s end, he signed a contract with Rogle in Sweden.

Although Sterner’s NHL experience was brief, he paved the way for Europeans to make their way to North America and become some of the finest players in the history of the league. Over the last six decades, the Blueshirts have benefitted from the contributions of European players, and Swedes in particular. From Anders Hedberg and Ulf Nilsson in the late-1970s and early 1980s, to players such as Tomas Sandstrom and Jan Erixon during the 1980s, Mika Zibanejad currently, and, of course, Henrik Lundqvist throughout his Hall-of-Fame 15-year career, Swedish players have made an indelible mark on Rangers history.

And it all began with Ulf Sterner, who made hockey history six decades ago today, laying the foundation for the great European players who followed in his footsteps.