After the NHL granted Washington an expansion franchise in June of 1972, things were mostly quiet aside from the ongoing construction of the Capital Centre, the team’s first home in Landover, Md. Majority owner Abe Pollin hired longtime Boston Bruins fixture and Hockey Hall of Famer Milt Schmidt as the team’s first general manager in April of 1973, and in January of 1974, Pollin and Schmidt announced that the District area’s newest pro sports team would be called the “Capitals.”

But for the better part of two years, the Caps were a team in concept only; they were a team with no players.

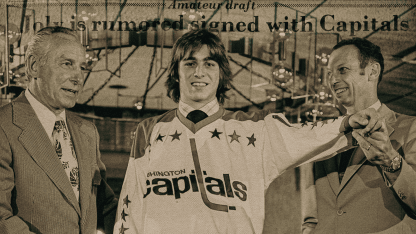

It was 50 years ago at this time that the Washington Capitals went from being a team in concept only to being a team with some actual players. Although the process was kept under wraps as it was going on, the Caps chose defenseman Greg Joly – then two days shy of his 20th birthday – with the first overall selection in the 1974 NHL Entry Draft, and the blueliner became the first player in franchise history.

Joly was selected on May 28, 1974, as the three-day process of the 1974 NHL Entry Draft got underway via conference call from Montreal. Weeks earlier, a series of coin tosses had determined that the Caps would have the first overall selection in the 1974 amateur draft and the Kansas City Scouts, the team that accompanied Washington into the NHL in 1974-75 would choose second.

The Scouts won coin tosses to pick first in the June 12, 1974 expansion draft and in the goaltender phase of the expansion draft, while Washington won coin flips to select first in the amateur draft and the intra-league draft, in which players could be selected from minor league rosters. The intra-league draft was a year away from being defunct; it lasted from 1952-75 and was replaced by the waiver draft in 1977, an annual fall ritual in the NHL until 2003.

Preparation for the ’74 Entry Draft began the year before when Schmidt was hired, becoming the team’s first employee. Schmidt quickly added a handful of scouts who would join him in scouring the pro and junior leagues of North America to evaluate and analyze hundreds of players who might be available for selection in either the expansion draft or the amateur Entry Draft.

Schmidt’s early front office cohorts included assistant GM Lefty McFadden, who had been the GM of the IHL’s Dayton Gems. Red Sullivan was the Caps’ first chief scout; following a successful NHL playing career in the 1950s, Sullivan had gone behind the bench as head coach of the Rangers and later the Penguins. He would end up serving a short stint as Washington’s bench boss as well.

Chirp Brenchley was the Caps’ east coast scouting supervisor. Born in England in 1912, Brenchley had connections to a previous pro team in the District; he played three seasons for the Washington Lions (Eastern Hockey League and later AHL) in the 1940s. After a long career coaching in the minors, he went into scouting, working for Pittsburgh before joining the Capitals. Brenchley’s west coast counterpart was Lou Jankowski, a former NHL player and the grandfather of current NHL forward Mark Jankowski. (Along with Caps’ assistant general manager Ross Mahoney, the late Lou Jankowski is a member of the inaugural class of 45 inductees into the Western Canada Professional Hockey Scouts Foundation’s Wall of Honour in July.)

The 1974 NHL Entry Draft was a notable and noteworthy one in that it became the first draft ever in which “underage” players could be chosen. Because the rival World Hockey Association – which began play in 1972-73 – was already drafting players who were younger than the 19-year-old minimum NHL draft age at the time, the NHL board of governors agree to do the same in the 1974 Draft, but with some modifications. Eighteen-year-old players could only be selected in the first or second rounds of the NHL draft, and clubs could only choose a single underaged player in that ‘74 draft.

Because of the heated competition for players between then WHA and the NHL, both circuits operated behind a cloak of concealment; the NHL opted to conduct its ’74 Draft via secret conference call. The League reasoned that the nascent WHA wouldn’t be able to poach the same players if it didn’t know which players the 18 NHL teams had selected; the NHL hoped its clubs would be able to choose and subsequently sign its selections swiftly, before the WHA was even aware of which players had been chosen.

And before the Draft was even underway, there was intrigue involving the Caps and defenseman Pat Price, rated as one of the top picks in the ’74 Draft. One of the newly available 18-year-olds, Price was in the midst of a stellar junior career with the WHL Saskatoon Blades, and the Boston Globe erroneously reported that Price would be Washington’s first pick in the draft. But in pre-draft negotiations, Price came to terms on a multi-year agreement with the WHA’s Vancouver Blazers. Vancouver reportedly offered half a million more than the Capitals were willing to venture, so Price opted for the big bucks from the Blazers.

The Caps then turned their attention to another WHL blueliner, Regina’s Joly. Having spent decades in the Boston organization as a player, coach, manager and executive, Schmidt had seen the transformative effect of blueliner Bobby Orr on the Bruins’ fortunes upon arrival in 1966, and there’s been a long-held roster-building tenet in the NHL that teams are built from the net out. With no goaltender worthy of a first overall selection, Joly – ranked as the seventh-best prospect by The Hockey News – became Washington’s guy. Less than three weeks before the Draft, Joly helped the Regina Pats to the 1974 Memorial Cup championship, and he won the Stafford Smythe Memorial Trophy as MVP of the tournament.

“There is no Bobby Orr,” said Brenchley to The Washington Post’s estimable Robert Fachet in the May 28, 1974 edition of the paper. “But it’s a fair crop this year. There are plenty of good, tough kids. We’re going to find out who did the scouting and who didn’t. It’s easy to pick them out when they’re outstanding.”

While the draft proceedings were still ongoing – it took the 18 GMs more than seven hours to draft the first 60 players on day one – the Caps flew Joly into D.C. and had him at Capital Centre for a press conference, where he became the first player ever to pull on the team’s newly minted red, white and blue sweater with stars and stripes.

“I’ve had my fair share of fights, and I’m not going to back down from anyone, but I figure I’m more use on the ice than in the penalty box,” Fachet quoted Joly as saying in the May 29, 1974 edition of The Post.

“I’m quite capable of jumping from junior into the NHL. I’ve kind of idolized these guys all my life, but I think one shift on the ice will get me over that.”

Few knew it at the time, but Joly had also been the first overall selection in the 1974 WHA Secret Amateur Draft; the Phoenix Roadrunners made him the first player taken in that draft as well. Washington was able to get Joly’s signature on a five-year contract worth a reported $400,000 almost immediately after he was drafted, essentially making the Roadrunners’ selection a wasted pick at that juncture. But Joly had soured on the WHA before the Roadrunners selected him.

“Their people [WHA] bothered a lot of us as our junior season was still on,” Joly told Russ White of The Washington Star-News. “We got bugged like heck during Memorial Cup. I didn’t go for it. I never intended to talk to Phoenix. I wanted the NHL.

“I doubt that offer would have changed my mind. They would have had to make a substantially better offer than Washington. I mean really substantial.”

Schmidt was effusive in his praise for the first Capital.

“Defensemen are the hardest to come by,” Schmidt told White. “Some teams want real aggressive defensemen, but I preferred a guy who could play defense well but could also move the puck out of our zone with so many clubs placing so much emphasis on forechecking.

“He’s the kind of defenseman everyone has been looking for since Bobby Orr started having such success with Boston. Greg does equally well carrying the puck or passing it. The present style in the NHL is dominated by forechecking, and if you can’t move the puck, you’re in trouble.”

Speaking of trouble, Schmidt had one more thought. “If Greg Joly doesn’t make the hockey club the first year, we’re in trouble.”

Joly made the team. He collected his first NHL point (an assist) in the Caps’ very first game, and he scored Washington’s first goal of its second season in the League. But Joly also suffered an injury – an inflamed Achilles’ tendon – in the Caps’ first training camp, and he incurred a knee injury less than two months into his first NHL season. A hairline fracture in his ankle curtailed his sophomore NHL season.

Almost two and a half years after he had become the Caps’ first ever player, Joly was quietly dispatched to Detroit in a Nov. 30, 1976 trade, a deal that brought the loquacious Bryan “Bugsy” Watson to Washington.

Joly’s NHL career was further plagued by injuries with Detroit; he had his best NHL season in Motown in 1977-78, only to suffer a serious wrist injury in the playoffs against Montreal in the spring of 1978. That injury required bone graft surgery, keeping him sidelined for 10 months. He never played a full NHL season after that, though he played on two Calder Cup champion teams with AHL Adirondack. Joly’s NHL career consisted of just 365 games, only 98 of which came with Washington.

Because of the secrecy surrounding the 1974 NHL Entry Draft, the Caps didn’t unveil the rest of their selections for a few days after the completion of the draft. That’s when the world learned that Washington chose underaged 18-year-old winger Mike Marson with its second pick (19th overall) in the ’74 Draft. Marson, a Black player from Scarborough, Ont., also made the Caps’ opening night roster in the team’s inaugural 1974-75 season, following in the footsteps of the great Willie O’Ree to become just the second Black player in League history, and the first in a decade and a half.

A power forward from the Sudbury Wolves of the OMJHL (now OHL), Marson stood 5-foot-9 and tipped the scales at 200 pounds.

“I’m getting the opportunity to do what I’ve worked hard for, what I’ve dreamed about,” Marson told White in the May 30, 1974 edition of The News-Star. “If it can be arranged, I hope I’m signed in a couple of days.”

Marson was also very aware of what he was in for as the League’s second Black player and its first in nearly a generation.

“People are saying that it’s like the Jackie Robinson story all over again,” said Marson. “Of course it isn’t. That was 1947. This is 1974, the Space Age. Sure, I’m going to have troubles. I had them in junior hockey. I overcame them with the juniors, and maybe some of the situations were tougher than what lies ahead.

“I’m entering the professionals now. I’ll be dealing with men now – not young men like in the juniors. I imagine a few gentlemen will try to get my goat. I don’t intend to let them.”

During O’Ree’s NHL playing days with Boston, Schmidt was the Bruins’ coach. Marson’s father – S.A. Marson – recalled hearing a radio broadcast on the CBC – Canadian Broadcasting Company – soon after O’Ree joined the Bruins in the late 1950s, and he recounted that broadcast for White.

“Milt Schmidt was being interviewed,” the elder Marson recalled. “He was the coach of the Boston Bruins, and he was talking about Willie O’Ree, the first black hockey player. Schmidt was emphatic that color made no difference, that O’Ree was as much a Bruin as any of his white teammates.”

“This is a dream come true,” added papa Marson.

Schmidt reiterated his thoughts upon announcing the Marson pick.

“Color had nothing to do with our picking Mike Marson,” Schmidt said. “The kid is a powerful skater, capable of playing in the NHL as a 19-year-old. He’s all business, a guy who doesn’t necessarily look for trouble, but one who won’t back away from it.”

Joly and Marson were both in the lineup for Washington’s first-ever game, on Oct. 9, 1974 against the New York Rangers at Madison Square Garden. The Caps’ two top picks were both excellent prospects, but both also found the jump to the NHL much more difficult. Both earned and were given the opportunity to play in the League right away, but both also ended up needing and getting some more minor league seasoning along the way.

The first few seasons of Caps’ hockey were sub-mediocre – to put it politely – and the constant losing combined with the revolving door of personnel on the ice (39 players in that first season), behind the bench (three different head coaches that first season) and upstairs (Schmidt’s tenure as GM lasted less than two seasons) made Washington one of the worst places for impressive and impressionable young prospects to land.

Joly is often listed among the biggest draft busts of all time, and history and hindsight both show that Schmidt and his scouts could have done better. But Joly wasn’t a “bad” pick; he was a certain first-rounder who ran into some bad luck with injuries, and the situation and the losing culture attached to the expansion Caps weren’t at all conducive to growth and development of young players. Marson lasted twice as long in D.C. as Joly did; Marson spent five years in the organization – longer than any of the 25 draftees from 1974 – before being sent to Los Angeles in a June, 1979 trade.

It’s not difficult to envision the careers of both Joly and Marson playing out differently if they’d been fortunate enough to be drafted by one of the non-expansion clubs of the time.

A total of 247 players – the most ever – were selected over the course of the three-day proceedings. In those days, teams could keep selecting players until they decided they had enough; and the Caps chose a record total of 25 players in the ’74 Entry Draft. Of those, only six ever made it to the NHL, and Joly’s total of 365 games played in the League topped that group of a half a dozen skaters.

When it was all said and done, the Caps drafted a total of just 884 NHL man-games played, ranking them 14th among the 18 NHL clubs at the time. Expansion teams such Philadelphia and Buffalo had managed to become competitive quickly on the strength of strong drafts early in their existence, but the Caps were unable to follow their skate steps in that regard. Washington would struggle mightily to ice a competitive club for the better part of a decade.

But there were some good hockey players to be had in the 1974 Draft, and the two teams that did the best work during the secrecy cloaked draft proceedings were both rewarded with dynastic stretches of multiple Stanley Cup championships.

The Montreal Canadiens and GM Sam Pollock were light years ahead of the rest of the League in their grasp of the importance of the Draft, which began in 1963 but didn’t morph into its current form until 1969. The Habs won their second consecutive Cup in 1969, but because of Pollock’s relentless drive to harvest more draft picks, Montreal still managed to maintain a cluster of first-round picks in virtually every draft, including the 1968 affair in which it had each of the first three overall choices.

When the Draft took on its current shape in 1969, the defending Stanley Cup champs got richer again, holding each of the top two overall picks and using them on Rejean Houle and Marc Tardif, respectively. Montreal then had two first-rounders in the 1970 Draft, three in 1971 (when they took Hall of Fame defenseman Larry Robinson in the second round), four in 1972 and somehow only one in 1973.

Not to worry, kid. Pollock amassed five (!) of the 18 first-round picks in 1974, managing to convince Vancouver, St. Louis, Atlanta and Los Angeles – all recent expansion entries – to fork over their own first-rounder to the benevolent Canadiens in exchange for a soon-to-be broken down, high mileage Montreal vet.

Fueled by those five first-round picks in 1974, the Canadiens drafted a remarkable total of 3,592 man-games, hitting on 11 of their 18 picks overall. No other team managed to hit on as many as eight picks, and that was the Rangers, whose total of 23 players taken was second only to Washington’s 25. By 1975-76, the Canadiens were back in the winner’s circle with another dynastic team, hoisting the Cup for what would be the first of four consecutive springs.

When the New York Islanders entered the NHL as an expansion team two years ahead of the Capitals, the Isles and architect Bill Torrey had the good fortune and sense to draft franchise defenseman Denis Potvin with the first overall pick in 1973, the Isles' second amateur draft. The Isles won only a dozen games in their own first miserable season in the League, but the prize for their poor inaugural season was Potvin, who was clearly a foundational piece the Isles could build around and upon.

The 1974 Entry Draft landed New York two more critical pieces for its own pending dynasty. With the fourth overall pick in the ’74 Draft, the Islanders landed future Hall of Fame power forward Clark Gillies. And with their second-round choice, the Isles landed another future Hall of Famer and another foundational piece, franchise center Bryan Trottier. Although the Isles clicked on only four of their 19 selections – only Los Angeles (three) did worse – those four players combined to skate in 3,372 NHL games, and all four of them (defensemen Dave Langevin and Stefan Persson were the others) ended up with four Stanley Cup championship rings when the Isles won four straight Cups from 1980-83.

Clearly, the Caps could have and should have done better at the 1974 Draft. There were some foundational pieces there for the taking, players that could have helped lift the team to respectability sooner. Given the level of experience in Washington’s front office and scouting staff, it should have done better, at least in the amateur Entry Draft; the deck was completely stacked against them in the expansion draft that took place a couple weeks later. But the Caps had to start somewhere, and that somewhere was with Joly, half a century ago.