From the time he was appointed as the first ever general manager of the Capitals in April of 1973, Milt Schmidt spent 13 months assembling a scouting staff, and then joining them in scouring the pro and amateur hockey leagues of North America in preparation for the team’s first amateur draft and its expansion draft.

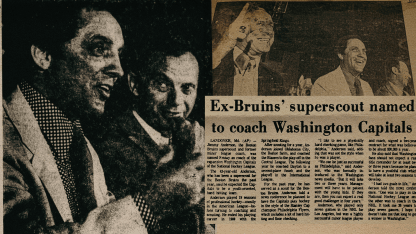

In between those two events in the late spring of 1974, Schmidt named Jimmy Anderson as Washington’s first head coach. The announcement was made on May 30, 1974 and Anderson arrived in town from his Springfield, Mass. home for a news conference the following day.

Writing in The Republican (Springfield, Mass.) in a column entitled “Anderson Gets His NHL Chance,” on May 31, 1974, Jim Fox opined: “Anderson was on hand for the announcement, and everyone who knows him in Springfield has to wish him luck. Though he never played in the NHL, Anderson has a wide hockey background. He was one of the all-time AHL scoring greats, has coached here with the Kings and in the Bruins organization and has been scouting for the past year with the Bruins.

“Anderson’s ideas on the [expansion] draft should come in handy at the Montreal meetings. And his ability to work with kids should make him an ideal coach of an expansion team.”

Fox also added a prescient closing paragraph to his piece: “The job isn’t going to be easy. The Caps figure to take it on the chin for a considerable time. It’s even been suggested that the first coach of the Caps could be the fall guy. But the lure of coaching in the NHL – and with Schmidt, one of the best-liked men in the game – has to be irresistible to an old hockey man like Anderson.”

There was one error in the Fox piece; Anderson did actually play in the NHL. At the age of 37 and after a long and fruitful career in the minor leagues – virtually all of it with AHL Springfield, where he played 16 seasons – Anderson spent a month with the Los Angeles Kings in their first season in the NHL. Anderson totaled one goal and three points in seven games with Los Angeles before returning to Springfield where he closed out his playing career in 1969-70.

Anderson was born in Pembroke, Ont. in 1930, a couple of decades too soon to fully benefit from the sudden and rampant employment boom in major league pro hockey that ran from 1967-79, but he was at a prime age – 43 – to benefit from the ancillary coaching boom of the time.

Anderson and Schmidt shared a previous employer, the Boston Bruins. During the latter stages of Schmidt’s lengthy Beantown tenure of 37 years as a player, captain, coach and general manager, he hired Anderson to coach Boston’s Central Hockey League affiliate in Oklahoma City of the Central League. Anderson had just finished his own distinguished playing career in the AHL, going directly from the playing roster of the AHL Springfield Kings to being the team’s interim head coach in 1969-70.

Previous Springfield head coach Johnny Wilson – the uncle of ex-Caps bench boss Ron Wilson – was summoned to Los Angeles and named L.A.’s interim coach when the team got off to a slow start in ’69-70 and fired coach Hal Laycoe. Anderson filled Wilson’s shoes while he was coaching the NHL Kings. But by season’s end, Wilson was back behind the bench in Springfield, where he led Springfield to a Calder Cup crown the following season.

Schmidt offered Anderson the head coaching gig at Oklahoma City of the Central Hockey League in 1971-72. With the Blazers that season, Anderson’s reputation of developing young players began to flourish; the Bruins credited him with aiding the growth of prospects such as Gregg Sheppard, Chris Oddliefson and Dave Forbes. The Blazers finished below .500 that season, and they were bounced in the first round of the playoffs by eventual champion Dallas.

In 1972-73, the Bruins withdrew from Oklahoma City; their top farm club in those days was the AHL Boston Braves, coached by Bep Guidolin at the outset of the ’72-73 season. Schmidt moved Anderson to Dayton of the International Hockey League, where Lefty McFadden’s Dayton Gems were annually among the best clubs in that circuit. The Gems reached the Turner Cup Final in four of five seasons to conclude the previous decade, winning back-to-back Cups in 1969 and 1970.

Anderson’s Gems bowed out in the second round of the playoffs in his lone season in Dayton, and Anderson moved into the Bruins’ scouting department for the ’73-74 season. McFadden also departed Dayton around this time; Schmidt hired him as his assistant GM in Washington.

After 11 seasons behind the Boston bench, Schmidt became the Bruins’ general manager in 1967. He led the club to two Stanley Cup titles – ending a 29-year championship drought in Beantown – in his five seasons on the job, and he left the Bruins after more than three and a half decades to become Washington’s first GM.

Clearly, Schmidt was still somewhat connected to the Bruins as he was helping to get the Caps off the ground in 1974, so reporters of the day were rightfully fixed on the Boston organization as they tried to determine who might land the job as Washington’s first bench boss. Anderson’s name had been mentioned as a possibility in the papers, but a late curve ball came along in May of 1974 after the Philadelphia Flyers won the Stanley Cup in six games, defeating the Bruins in the Cup Final.

A week after the Flyers hoisted the Cup, Bruins coach Bep Guidolin quit when the team wouldn’t acquiesce his request for a five-year contract extension. After being promoted from AHL Boston to replace Tom Johnson as the Bruins’ coach midway through the ’72-73 season, Guidolin led the B’s to the Cup Final in ’74. Knowing that he was unlikely to get much of a raise from his $25,000 annual salary from the penurious Bruins, he took aim on job security instead. That request was shot down by Bruins GM Harry Sinden, who ironically quit as the B’s coach a few years earlier because his own request for a multi-year pact was rebuffed. In turning down Guidolin’s request, Sinden noted that only Toronto’s Red Kelly had the luxury of a five-year pact among the NHL bench bosses of the time.

Armand “Bep” Guidolin is best known as being the youngest player (he was 16) in NHL history, a distinction he is virtually certain to hold forever. His own NHL playing career ended at the age of 26; there were whispers of him being blackballed from the NHL as a player because of his vocal support for an NHL players’ union, which did not exist at the time. Days before the 1974 NHL Entry Draft and weeks ahead of the ’74 expansion draft to stock the Capitals and the Kansas City Scouts, Guidolin was suddenly on the market, and his career NHL coaching mark of 72-23-9 (.736 points percentage) made him an attractive candidate not just for the Caps and the Scouts, but also for the 16 other established teams in the circuit.

The May 28, 1974 edition of The Washington Post carried a Robert Fachet story entitled, “Guidolin Quits Bruins, Capitals Interested.” The body of the story carries a Schmidt quote: “I haven’t heard from him. I have not contacted him. I did not contact him earlier.”

Pressed further, Schmidt also added, “If he is no longer associated with them, I would be interested in discussing the job with him.” In the story’s final paragraph, we learn that Schmidt has discussed the position with several candidates, including Boston scout Jimmy Anderson.

Clancy Loranger’s column in the May 31, 1974 edition of The [Vancouver] Province erroneously suggested that Guidolin would be the “likely” choice for Schmidt: “Guidolin isn’t expected to be left standing around very long, though. He’s already been contacted by four other NHL teams, and will likely join his old boss, Milt Schmidt, as coach of the Washington Capitals.

“Says Schmidt of Guidolin: ‘I think he has done a tremendous job. He said a few things maybe he shouldn’t have said in the playoffs, but you have to take into consideration he was under a great deal of stress and strain. What do I think of him as coach? One hundred percent.’”

Meanwhile, Schmidt was quietly assuring Anderson that the job was his. Fifty years ago today, Schmidt and the Caps made it official, and on May 31, 1974, Anderson was at Capital Centre for a press conference to introduce him as the Capitals’ first bench boss.

“We can be just as successful as Philadelphia,” said Anderson at his introduction. “But it will take two or three years. Management will have to be patient with the young kids. If they are, then you can expect a real good challenger in four years.

“I had two goals in life. One was to play in the NHL. It took me 36 years to play seven games. I hope it doesn’t take me that long to get a winner in Washington.”

When asked about his choice, Schmidt mentioned that Anderson wasn’t necessarily his first choice. “I put them all in the hat and his name was the one that came to the top.”

Schmidt also shot down the rampant speculation that Guidolin was going to be Washington’s coach.

“It was all newspaper talk,” Schmidt was quoted as saying in wire service reports. “I did not contact him and he did not contact me.”

A week after Anderson’s introduction in the DMV, Guidolin was in Kansas City where he was named the first head coach of the Caps’ expansion sibling, the Kansas City Scouts.

Anderson’s work at whipping Boston center Derek Sanderson into physical shape was also cited as a positive on his résumé. Following Sanderson’s ill-fated foray as the highest paid player in all of pro sports with the upstart World Hockey Association’s Philadelphia Blazers in 1972 – a dalliance that lasted all of eight games before he suffered a back injury from slipping on a piece of trash in a game at Cleveland – Sanderson subsequently had his contract bought out, and he was back with the Bruins before the end of the 1972-73 season, thanks to Anderson’s one-on-one work with the brash Bruin.

Anderson also had a fairly thorough grasp of the upper minor leagues at that time, being only a few years removed from his own AHL playing career, and having coached in the CHL and the IHL, and having spent the ’73-74 season as Boston’s chief pro scout. Some of the newspaper reports of the day referred to Anderson as a “superscout.”

“I have a thorough assessment of the American Hockey League,” he said at his introduction. “There are a lot of fine players there that can play in the NHL that are just waiting to be plucked. A few years ago, I didn’t think they’d be able to play, but the league has expanded so fast and diluted itself, I think they are ready now.”

During the Original Six seasons of the NHL (from 1942-43 through 1966-67) there were just over 100 “jobs” available at the highest level of the sport. Beginning in 1949-50, NHL clubs were allowed to dress 17 players (exclusive of goaltenders), and the number didn’t increase to the current 18 players plus two goaltenders until 1982-83. For much of the Original Six era, teams carried just one goaltender, so there were essentially 108 roster spots available.

Concurrently, there were a number of high-level minor league professional circuits in operation in those days. The American Hockey League was founded in 1936-37, and its membership was as high as 10 teams during the Original Six era. The Central Hockey League (neé Central Professional Hockey League) began operation in 1963-64 and disbanded in the 1980s with a membership as high as nine teams. The Eastern League lasted from 1933 to 1973 with as many as a dozen teams – including one in Washington for several seasons – and the International League ran from 1945-2001, with membership as high as 19 teams in the latter stages of its existence, but more typically in the 6-8 team range during the Original Six days.

The Western League was arguably the closest outfit to an NHL rival in those days; from the mid-1940s to the mid-1970s, the WHL was a premier minor league circuit with California-based teams and west coast clubs among its 6-9 members during that time. The pay and quality of play was good enough to suppress the NHL aspirations of some skaters of that era.

While there weren’t very many NHL jobs available for that quarter century period of time, there were plenty of viable options for pro players who weren’t quite good enough to crack the rosters of one of those six top level teams. Plenty of players forged long careers in the American, Central, Eastern, International and Western Leagues, some of which were used as NHL farm clubs in those days, and many of those players got a taste of NHL action when an injury paved the way for a temporary roster berth.

This is the world that Jimmy Anderson lived in when he broke into pro hockey with the Detroit entry in the IHL in 1949. The 18-year-old left wing was the second leading scorer for the Detroit club in that 1949-50 season, playing under future NHL coach Jim Skinner and with another future Hall of Fame NHL coach – defenseman Al Arbour – anchoring the blueline.

For more than two decades, Anderson toiled in the International League, the Western League and mostly in the American League, with quick stops in lesser circuits such as the Maritime Major Hockey League (MMHL), the Quebec Senior Hockey League (QSHL), and the Quebec Hockey League (QHL).

Following a few nomadic seasons early in his career, Anderson landed in Springfield, Mass. with the AHL Springfield Indians in 1954-55, an outfit coached by the legendary Hockey Hall of Fame defenseman – and coaching taskmaster – Eddie Shore. Aside from a short, half-season stint in the QHL in 1957-58 and a brief and long-awaited cup of coffee in the NHL with Los Angeles in 1967-68, Anderson stayed in Springfield through the end of the 1960s, eventually playing 943 games for the Indians, who changed their nickname to “Kings” in 1967-68 to mark their affiliation with the newly minted Los Angeles NHL club.

The AHL rookie of the year in 1954-55, Anderson racked up a dozen seasons with 20 or more goals with Springfield, eclipsing 30 goals on seven occasions and thrice reaching 40 during an era in which teams typically played 70-72 regular season games. Anderson was the AHL goal scoring leader twice during his career, and he had seven seasons in which he landed in the League’s top 10 in goals and/or scoring. He was also an important piece of the Springfield team that won a remarkable three straight Calder Cup titles from 1960-62, the only “three-peat” in the eight-decade history of that storied circuit. In 2009, Anderson was inducted into the American Hockey League Hall of Fame.

While Anderson was of a prime age to benefit from the expansion era on the coaching side of the game, and while he had a thorough knowledge of the game and its players, it wasn’t nearly enough to overcome the absolute lack of talent the Caps were left with following the expansion draft. There were a dozen NHL clubs added in less than a decade to what had been a six-team circuit, and the Caps and Scouts were the last of those two teams. There was virtually nothing left in the cupboard for them in terms of viable talent, and the 1974-75 Capitals posted an 8-67-5 record, still the worst first-season showing for any NHL club in history.

Anderson wasn’t able to make it out of the first season with his job; he was dismissed hours before a home game with the New York Rangers on Feb 11, 1975; the Caps had a dismal 4-45-5 record at the time. An optimist to the bitter end, Anderson’s message was positive even after a 7-3 setback to the Rangers in New York on Feb. 9 in what would prove to be his swan song as an NHL coach: “We’ve been good in the last six or seven games. We have a good attitude. We have been 100 percent better in the second half of the season.”

Schmidt was not happy to be making the change, but the constant losing was wearing on him. Anderson was kept on the Caps’ payroll as a scout, but he was not present at the news conference announcing his dismissal.

“I appreciate his work, and I regret the move,” said Schmidt. “I regret the change.”

The loss to the Rangers in Anderson’s last game left the Caps with a 1-21-1 mark in their previous 23 contests. Washington picked up a win in October, another in November, another in December, and another in January. It was still seeking its February victory when chief scout Red Sullivan was named to replace Anderson. Sullivan had coached the Rangers for four seasons in the early 1960s and was the first ever coach of the Pittsburgh Penguins, lasting just two seasons at that post.

At the press conference, Sullivan insisted he was no interim coach.

“I’m not in here to finish the season,” Sullivan is quoted as saying in the Feb. 12, 1975 edition of The Washington Post. “I’ve never taken a job on that basis. I hope I can stay behind the bench in Washington for 10 years. I can’t turn it around overnight, but I can be an asset to the organization.”

Sullivan’s Caps won his debut against the Rangers that night, but it was far from a normal night at the rink. Back home from a five-game road trip while the Ice Capades took over the Capital Centre, Sullivan was set to make his Caps’ coaching debut at home against his former Rangers team on Feb. 11, hours after that introductory press conference. But the combination of the Ice Capades’ stay and a Feb. 10 Led Zeppelin concert left the ice in unplayable shape.

This remarkable passage is from Daniel McCoubrey’s story in the Feb. 12 edition of The Post: “After the Ice Capades pulled up skates [sic] Sunday night [Feb. 9], the surface was almost immediately covered with boards for Monday night’s concert. Disturbances at that musical offering left many broken doors and the smell of the mace used to quiet the gate crashers. The biggest problem was clearing the uncovered ice surface of the paint used in the Ice Capades performances.

“Scraping began at 3 p.m., but by the scheduled starting time huge globs of white coloring covered the faceoff surfaces, blue lines and red line.”

It took hours to make the ice playable; the game didn’t start until 9:56 p.m. and wasn’t completed until after midnight. After falling behind 3-1, the Caps rallied for six unanswered goals to make a winner of Sullivan in his debut. The 7-4 triumph represented the most goals the Caps had scored in a game in their brief history.

Sulllivan’s own stint behind the Washington bench proved to be even shorter than Anderson’s; Sullivan resigned after about 40 days on the job. The Caps went 2-16-0 under his direction.

Neither Sullivan nor Anderson ever coached in the NHL again. After the dust settled, Russ White of The Washington Star-Times reached out to Sullivan for his reaction.

“It hurts,” admitted the Caps’ first coach. “It may be just what the club needs. I wasn’t Red. I tried my best the way I thought we could build. I was in expansion hockey and they were very fair to me. Red Sullivan probably told me more of what to expect and how to handle myself than anyone else.

“He told me whenever I was really down, that was when I could tell myself that I was earning twice what they were paying me. At times maybe I was. At times maybe I wasn’t.

“This didn’t jump up and hit me cold. I knew they would have to make a change if we didn’t start winning. I guess I knew last week while we were on the West Coast. I came out of the Los Angeles Forum and stared up into the dark sky. There I was standing alone and hearing things. We had lost. I was running out of time. It was a game we should have won.”

There definitely weren’t many of those type of games for the Caps in 1974-75. Jimmy Anderson was a good man with a strong hockey background who was put in an impossible situation. Just as the playing careers of original Caps Greg Joly and Mike Marson would have turned out much differently had they been able to begin their respective NHL journeys in other organizations, the same is true for Anderson’s ill-fated coaching career in the League.

After his contract with the Caps expired, Anderson spent 19 years scouting for the Los Angeles Kings. As a retired senior citizen back home in Massachusetts, he taught young children how to skate. He passed away at the age of 82 on March 10, 2013.