Over the past 57 years, the NHL has grown from a small, six-team outfit mainly confined to the northeast corner of the continent to a sprawling 32-team circuit that spans from Los Angeles to Montreal and south Florida to Vancouver. The NHL boldly doubled in size from six to a dozen teams in 1967, and it has grown in gradual fits and starts since, adding one, two or four teams at a time until reaching its current shape with the addition of Seattle in 2021, a long-awaited and delayed addition, as you’ll see.

The last six decades have brought many an expansion success story, from the St. Louis Blues making the Cup Final in each of the first three seasons of their existence, to the Philadelphia Flyers’ back-to-back Cup championships in the mid-70s to the Florida Panthers quick start under the late Roger Neilson to the modern expansion marvels in Vegas, where the Golden Knights advanced to the Cup Final in year one and won the championship at the conclusion of season six.

But our story today isn’t one of success. We’re here to discuss the oft-neglected tale of the rock bottom moment of the NHL’s checkered expansion past, the 1974 expansion draft which stocked the League’s two newest teams – the Kansas City Scouts and the Washington Capitals – with an assortment of flotsam and jetsam discarded from the 16 existing clubs in the circuit, 10 of which were less than a decade removed from their own NHL births.

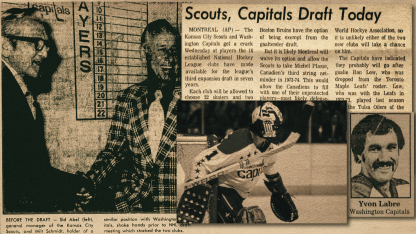

When Caps’ general manager Milt Schmidt and Kansas City counterpart Sid Abel – Hockey Hall of Famers, both – assembled in Montreal half a century ago today, on June 12, 1974, to pick over the table scraps and decaying remnants of what passed for organizational excess in those days, they were undertaking a task that had absolutely no chance of succeeding, the formation of a competitive expansion team that would begin NHL play in 1974-75.

Two weeks earlier, the Capitals participated in their first-ever NHL Entry Draft, and they hired Jimmy Anderson as the team’s first ever head coach. As Schmidt examined the protected lists of the 16 existing NHL teams in preparation for the Caps’ NHL expansion draft, he couldn’t have been happy or excited with what he saw. The League’s exponential growth left little in the talent cupboard for the Caps and Scouts.

In 1966-67, the final season of the NHL’s “Original Six” era, there were fewer than 120 “major league” hockey jobs to be had in North America. But with the NHL doubling in size in 1967-68 and then adding two more teams each in 1970-71, 1972-73 and 1974-75, the League tripled in size from six to 18 teams in less than a decade.

Concurrent to that exponential NHL growth, the rival World Hockey Association (WHA) appeared on the scene with a dozen teams in ’72-73. By the time the Capitals and the Kansas City Scouts were set to participate in the ‘74 NHL expansion draft, the dilution of talent in both the NHL and WHA circuits was extremely noticeable.

In 1966-67 – the final season of the Original Six era – a total of 157 skaters and 19 goaltenders (176 players) played at least one game in the NHL. In 1974-75 – the Caps’ first season in the League – there were 450 skaters and 51 goaltenders in the League, but there were also 246 skaters and 38 goaltenders who saw duty in the 14-team WHA that season. The number of players who played major league hockey more than quadrupled in less than a decade, without much of a corresponding shift at all in where those players were coming from.

In an era in which teams didn’t scout in Europe and in which more than 90 percent of all players hailed from Canada, there simply wasn’t enough talent to spread around to the newer major league hockey franchises in both the NHL and WHA. But the NHL was less concerned with that problem than with the $6 million membership fee it was pulling in from both the Caps and the Scouts to join the League, so it took the money and left its two newest teams with what could charitably be described as breadcrumbs.

When the Caps and Scouts huddled up to pick over the scraps left by the Original 16 some fifty years ago, North American pro hockey was vastly different than it is today, mostly because it was far, far less diverse in those days. In 1966-67 – the final season of the Original Six era – Canadians accounted for 96.6 percent of all players (170 of 176) who played in the NHL, and only three players came from the United States. Poland, Slovakia and the United Kingdom contributed the other three players.

In 1974-75, 450 skaters and 51 goaltenders saw NHL action, with 90.6 percent of those players hailing from Canada. The number of U.S. players increased to 31 (6.2) percent, and there were five Swedes, two players from France, two from the U.K. and one each from Italy, Netherlands, Serbia, Slovakia and Venezuela.

Contrast that to the just completed 2023-24 campaign, a season in which 924 skaters and 98 netminders saw action in at least one game. Canada now supplies just 45.9 percent of all players with the U.S. running second at 32.3 percent. The other 21.8 percent comes from the rest of the world.

In a July 21, 1974 piece in The Boston Globe – notably, several weeks after Schmidt and Abel drafted the original Caps and Scouts – Fran Rosa posited that two new frontiers would be tapped in order to keep up with the seemingly constant expansion of that era: U.S. colleges and Europe.

“The two sources of player supply that hockey will turn to showed up again last week: American colleges and Europe.

“With all the expansion going on in both the National Hockey League and the World Hockey Assn., it was inevitable the teams would watch American college hockey more closely.

“Along with it now has come a race to European talent. The Toronto Maple Leafs beat everyone to a pair of good Swedish players last season, Borje Salming and Inge Hammarstrom. The [WHA New England] Whalers a month ago signed Swedish twins Thommie and Christer Abrahamsson.

“And just a few days ago the Toronto Toros of the WHA got Vaclav Nedomansky from Czechoslovakia.

“Earlier this month the Atlanta Flames gave a multiyear contract to Dean Talafous, Wisconsin’s native-American center.”

Writing in the (Halifax, N.S.) Chronicle-Herald on June 12, 1974, the venerable (70 years in journalism, kids) Hugh Townsend quoted Schmidt’s stance on building the Caps into a contender: “I’m not going to run around trying to make the club an instant success by trading away draft picks. I’m going to stick with our kids just as Punch [Imlach] has done so successfully in Buffalo.”

After 14 months of scouring the continent for hockey talent, Schmidt and his scouting staff drafted a couple of dozen amateur players in late May in the 1974 NHL Entry Draft, the first in which Washington was a participant. With the first overall pick in that draft, Schmidt selected defenseman Greg Joly from Regina of the WHL.

“Joly is the type of guy on which to build a new club,” Schmidt told Townsend. “In my opinion he’s probably the best young defenseman to come along since Bobby Orr.”

Two weeks after drafting Joly and the other amateurs, Schmidt and Abel sat down to flesh out their respective organizations with 24 more players, all of them pros from the rosters of the 16 existing NHL teams at that time.

As is the case this year, June 12 was on a Wednesday in 1974. At 10 p.m. on Monday, June 10, 1974, Schmidt received the protected lists of the 16 NHL clubs. For 14 months, Schmidt could only speculate and hypothesize which players might be available to them in the draft. With the actual list in his hands, Schmidt had less than 48 hours to spend with the lists; he would join Abel at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal to commence the draft at 2 p.m. on Wednesday.

Each club was permitted to protect two goaltenders and 15 skaters, and each club could add a player to its protected list each time it lost a player. Established teams could lose no more than three players. Teams that lost goaltenders in the 1972 Expansion Draft – Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles and Montreal – were exempt from losing goaltenders in the ’74 draft, if they chose.

Unhappy with his contract offer from the Canadiens after winning the Conn Smythe in his first season and the Calder Trophy in his second (spend some time thinking about that; it’s unlikely to ever happen again) Habs goaltender Ken Dryden took the 1973-74 season off to work as a law clerk for a Toronto law firm. Dryden’s intention to return to the Habs in the fall of 1974 left Montreal with a bit of a glut in goal, so the Canadiens were willing to lose a netminder. The Habs and Kings opted not to use their goaltending exemptions, but the Bruins and Hawks both took the option.

Schmidt and the Caps won coin flips to determine which team chose first in the 1974 Entry Draft and the ’74 Intraleague Draft; Abel and the Scouts won the flips for the first goaltender and for the first skater in the expansion draft.

The goaltender portion of the draft was conducted first. The Scouts took Michel Plasse from Montreal, the Caps chose Ron Low from Toronto, Kansas City took Peter McDuffe from the Rangers and the Caps grabbed Michel Belhemeur from the newly crowned Stanley Cup champion Philadelphia Flyers. The Habs exposed Plasse so they could then add blueliner John Van Boxmeer – Montreal’s first-rounder from 1972 – to their protected list. Similarly, Philly exposed Belhemeur so it could protect defenseman Joe Watson, who had just helped the Flyers to the team’s first Stanley Cup title.

Low was Washington’s No. 1 netminder for the team’s first three seasons of existence, a stretch in which he saw more rubber than the Washington beltway. Low arrived in Washington with 42 games worth of NHL experience, all of it with Toronto in ’73-74. He started the Caps’ first game, recorded the team’s first victory and its first shutout, and was shelled on a nightly basis because of the utter dearth of talent around him. In each of his first two seasons with the Caps, Low posted an identical – and unsightly – GAA of 5.45 with save percentages in the .850s.

When he departed the District in the summer of ’77 – signing with Detroit as a restricted free agent – Low brought the Caps mutually agreed upon compensation in the form of a couple of future draft picks and center Walt McKechnie. Low played professionally into his mid-30s before going on to a career in coaching. He logged 145 of his 382 career NHL games with the Capitals, and he had the longest and most successful pro career of the four netminders chosen in the ’74 expansion draft, a low bar for sure.

Belhumeur’s NHL career began in 1972-73 when he posted a respectable 9-7-3 mark with a 3.23 GAA and a .903 save pct. with the Flyers. After spending the following season in the minors, he came to the Caps in the expansion draft. Belhumeur had the misfortune of becoming somewhat of a poster boy for the ravages of rampant expansion in the League; he famously failed to earn a victory (0-29-4) in 42 appearances in the crease scattered over two seasons with the Capitals, posting a 5.32 GAA in the process. The high point of his career with the Caps came on Oct. 23, 1974 in his second game with the team when he stopped two penalty shots in the same game against Chicago, the first NHL goalie to do so since the 1930s. After becoming a free agent following the 1975-76 season, Belhumeur played professionally for three more seasons, finishing his career at the age of 29. He logged 42 of his 65 career NHL appearances with the Capitals.

Kansas City scooped up the plum of the skaters with its first pick, Simon Nolet of the Flyers. Nolet had scored 19 goals in just 52 games with Philly in ’73-74, and there were few players available that offered much in the way of offense. Nolet was mainly available because of his age (33), but he led the Scouts in scoring (58 points) in K.C.’s first season, and he tied 19-year-old Wilf Paiement – the Scouts’ first ever amateur pick, selected immediately after the Caps chose Joly – for the team lead with 26 goals. Nolet was also the Scouts’ first captain.

Washington’s own first choice was Chicago’s Dave Kryskow, who had scored 34 goals in 52 games with CHL Dallas in ’72-73. Kryskow was the Hawks’ second-round pick in the 1971 draft, and he famously scored five goals in a playoff game in juniors, and later had a four-goal game in the minors with Dallas, with three of the goals coming shorthanded.

But Kryskow’s minor league scoring prowess never translated to the NHL; he had totaled just eight goals in 83 NHL games with the Hawks when the Caps made him their top choice among available skaters. Kryskow didn’t last the first season in Washington. He scored the Caps’ first-ever shorthanded goal on Dec. 19, 1974 and was dealt to Detroit for defenseman Jack Lynch on Feb. 8, 1975. After bouncing to Atlanta the following season, Kryskow jumped to the WHA where he finished his hockey career at the age of 26.

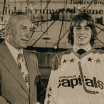

Schmidt’s next choice was defenseman Yvon Labre, who had more staying power than any of his expansion draft brothers. Most of the players Schmidt chose were out of hockey prior to their 30th birthday, but Labre was a rare exception, and just barely. His career was curtailed by injuries, but he finished his career as a Capital and was 31 when he laced up the skates for the final time on Valentine’s Day, 1981. Just under nine months later, the Capitals retired Labre’s No. 7 sweater. His total of 371 NHL games played and 334 played with the Capitals are both among the highest totals amassed by the 24 players the Caps selected in that expansion draft.

Switching back to the forward position, Schmidt tabbed Pete Laframboise of the California Golden Seals as his third choice among skaters. Laframboise was California’s second-round pick in the 1970 NHL Entry Draft, and he erupted for four goals in a game as a rookie against Vancouver, accounting for a quarter of his career-high total of 16 in that ’72-73 season. Laframboise’s goal total dipped to seven in his sophomore season, hence his availability to the Caps and Scouts. Like Kryskow, Laframboise didn’t last the first season in Washington; he was traded to Pittsburgh on Jan. 21, 1975. Laframboise finished up in the AHL at 29 in 1978-79.

As the former GM of the Bruins, Schmidt chose all three players Boston lost in that ’74 expansion draft, and Abel – who spent most of his career playing and working for Detroit – chose all three players the Red Wings lost. Schmidt’s first choice from the B’s was forward Bob Gryp, who holds the distinction of being the first ever Boston University player to skate for the Bruins. He played that one NHL game for Boston (in ’73-74) and got into another 73 games in two seasons with the Caps before finishing his career at the age of 27 in the minors.

Schmidt again turned his attention to the defense, choosing Gord Smith of Los Angeles, the older brother of New York Islanders netminder and Hockey Hall of Famer Billy Smith. Gord Smith was coming off a strong season with AHL Springfield, where he totaled 13 goals and 67 points in 76 games and won the Eddie Shore Award as the AHL’s top blueliner. After making his NHL debut the same night as the Caps did the same as a franchise, Smith stuck around long enough to play 286 games with Washington and 299 for his NHL career; he left D.C. when Winnipeg chose him in the 1979 expansion draft. Smith is one of the rare Caps expansion choices who was still playing beyond his 30th birthday; he spent most of his last four seasons in the minors, finishing up at the age of 32. Smith was a single day shy of his 30th birthday when he played his final NHL game with the Jets in November of 1979.

Next, Schmidt chose forward Steve Atkinson from Buffalo, another player with whom he had some familiarity. As Boston’s GM in 1966, Schmidt chose Atkinson with the sixth overall pick in the 1966 NHL Draft. Atkinson played one game with the B’s in ’68-69 before moving to St. Louis in the 1970 intraleague draft. Buffalo claimed him from the Blues early in the Sabres’ first NHL season, so Atkinson was a member of both the first Sabres and first Caps teams. He scored 20 goals with the Sabres in 1970-71, accounting for a third of his career total of 60 in the League. Atkinson holds the distinction of being the first Capital to score on a penalty shot, a feat he achieved on Feb. 1, 1975 at Vancouver, while Washington was shorthanded. Atkinson’s NHL career ended at the end of the Caps’ inaugural season of ’74-75, and he played in the minors through his age 29 season.

Coming from Philadelphia, forward Bruce Cowick was the Caps’ next pick. Cowick made his NHL debut in the 1974 Stanley Cup playoffs, getting into eight games with the eventual Cup champs, sufficient to have his name eternally etched onto the chalice. Cowick skated in 65 games for the expansion Caps in 1974-75, totaling five goals and 11 assists. St. Louis claimed him off waivers at season’s end, and Cowick’s playing career concluded the following season at the age of 24. He played a total of 70 NHL regular season games plus those eight playoff contests with Philly.

Denis Dupéré was Schmidt’s next pick, the third straight forward chosen by the Caps. Dupéré holds the distinction of being the Caps’ first-ever All-Star; he collected an assist in the ’74-75 All-Star Game at the Montreal Forum on Jan. 21, 1975. Dupéré was also Washington’s first ever 20-goal scorer; he netted his 20th goal of the ’74-75 season on Jan. 30, 1975 at Los Angeles. Less than two weeks later, he was traded to St. Louis for Garnet “Ace” Bailey and Stan Gilbertson. Dupéré logged 421 career NHL games – including 53 with Washington – before finishing his playing career at the age of 29 in 1977-78.

After taking three straight forwards, Schmidt again turned his attention to the blueline, snagging rearguard Joe Lundrigan from Toronto. Lundrigan had played well in a 49-game trial with the Leafs in ’72-73, but not well enough to avoid playing the entire ’73-74 campaign in the minors. Lundrigan was in the lineup for Washington’s first ever NHL game on Oct. 9, 1974, but he played in just two more games with the Caps that month. Lundrigan’s pro career concluded with AHL Hershey at the end of ’74-75, his age 26 season.

The twelfth of the 24 players chosen by the Caps was center Randy Wyrozub from Buffalo, an Edmonton native who was a fourth-round pick of the Sabres in their first ever NHL Entry Draft in 1970. In parts of four seasons with the Sabres, Wyrozub totaled eight goals and 18 points in 100 NHL games. Wyrozub was the first of four players chosen by the Caps in the expansion draft who never suited up for a regular season game with the team. Wyrozub spent the entire ’74-75 season with the Caps’ AHL Richmond farm team, finishing third on the team in scoring but strangely never being recalled by a Washington team desperate for useful players. Wyrozub jumped to WHA Indianapolis in 1975-76, then knocked around the minors for a few seasons, finishing his career at the age of 29 after the ’78-79 season.

Schmidt went back to the Boston organization for his next pick, forward Mike Bloom. After the Bruins won the Stanley Cup in 1972, Bloom was their first choice in the ’72 NHL Entry Draft, the last player chosen in the first round (16th overall). Bloom was coming off a strong season at WHL San Diego, where he totaled 25 goals and 69 points in 76 games in ’73-74. Bloom made his NHL debut in the Caps’ first ever game on Oct. 9, 1974, but like several of his fellow expansion draftees, his tenure in the organization would be short. Bloom was dealt to Detroit for Blair Stewart on March 9, 1975, late in the Caps’ inaugural season. Bloom played 201 NHL games – including 67 for Washington – before his pro career concluded in ’78-79 when he was 27. In his last season as a pro with PHL San Diego in 1978-79, Bloom scored 25 goals, four more than 42-year-old teammate Willie O’Ree.

Beginning with forward Gord Brooks as Washington’s 12th pick among skaters in the draft, the Caps were in the back half of the skaters’ phase of the draft. Brooks was plucked from the Blues, and he brought 32 games worth of NHL experience with him to Washington. Brooks racked up 20 goals and 40 points in half a season with WHL Denver in ’73-74, and he produced a respectable six goals and 14 points in 30 games with the Blues upon promotion to the NHL that season. Brooks was 24 when he took the ice for the Caps’ first ever game, but the team’s inaugural season in the circuit also proved to be his NHL swan song. Although he had a successful minor league career for the better part of another decade – wrapped around a brief pro foray in Austria – Brooks logged 70 career NHL games. He posted a goal and 11 points in 38 games with the Caps.

With their next pick, the Caps took another forward from St. Louis, and one with whom Brooks was quite familiar. Washington chose Bob Collyard, who hails from Hibbing, Minn. The Blues wagered a late pick on Collyard after his excellent collegiate career at Colorado College, and he went on to lead last place Denver in scoring (74 points, 10th in the WHL) in 1973-74. Collyard and Brooks were briefly teammates together in St. Louis, and they were linemates with CHL Kansas City, WHL Denver and NAHL Philadelphia. Collyard logged 10 NHL games with the Blues in December of 1973, but that was the entirety of his NHL career; he was waived days after the Caps’ first training camp and later hooked on with the NAHL Philadelphia Firebirds. Like Brooks, Collyard played professionally into his early thirties, carving out a career as a prolific scorer in a few different leagues with a couple of seasons in Germany as well.

Turning back to the blueline, the Caps next chose defenseman Bill Mikkelson from the New York Islanders, where he had been a member of the anemic (12-60-6) expansion edition of the Isles in 1972-73. Mikkelson played 15 games with the Kings in 1971-72 before going to New York in the ’72 expansion draft. After appearing in 72 of the Isles’ 78 games in their inaugural season, he spent the following campaign with AHL Baltimore. The nephew of 1947-48 Calder Trophy winner – and Belfast, Ireland native – Jim McFadden, Mikkelson was in the opening night lineups for the first NHL game ever played by both the Islanders and the Capitals. Mikkelson played just one more game with the Caps after the team’s inaugural season, retiring after the ’76-77 campaign at the age of 29. He logged 147 NHL games, 60 of them with Washington. Mikkelson’s son Brendan later played in the NHL and his daughter Meaghan represented Team Canada at three different Olympic games. She also played several seasons in the Canadian Womens Hockey League after a distinguished career at U. of Wisconsin. Like their dad, both Brendan and Meaghan Mikkelson were blueliners.

Schmidt’s final pick from the Bruins was next; right wing Ron Anderson was harvested from Boston where he had played two seasons with Boston University and two more with the AHL Boston Braves. Anderson was in the opening night lineup for the Capitals on Oct. 9, 1974 at Madison Square Garden, one of three Washington expansion draftees – along with Smith and Bloom – to make their debut the same night as the franchise. Anderson also scored his first NHL goal that night, joining Kryskow and Jim Hrycuik in lighting the lamp in a 6-3 loss to the Rangers. Anderson scored nine goals and totaled 16 points in 28 games for the Caps in ’74-75, and that’s the sum total of his NHL playing career as well. Anderson then went on to a lengthy collegiate coaching career at Merrimack before returning to the NHL as a scout with Chicago in 1999, and he has been with the Hawks in varying capacities since, having his name carved into the Cup three times (2010, 2013, 2015) over that span.

Schmidt went out west for his next choice, taking forward Mike Lampman from the Canucks. Drafted by St. Louis as the 111th player chosen of a total of 115 in the 1970 NHL Entry Draft, Lampman was, for a couple of months early in the ’72-73 season, the lowest drafted player ever to play in the League. By the time the Caps chose him in the expansion draft, Lampman had played 47 games over three seasons with the Blues and Canucks, totaling four goals and seven points. Lampman didn’t make the Caps’ varsity roster in ’74-75, and he was suspended after initially refusing an assignment to AHL Richmond. Lampman later had a change of heart, reporting for duty in late October to the Robins, coached in those days by Larry Wilson, father of ex-Caps bench boss Ron Wilson. Lampman worked himself into shape and debuted with the Robins in mid-November of 1974. After a good start at AHL Baltimore in ’75-76, Lampman was recalled to Washington, and he scored in his Caps debut on Nov. 15, 1975, biting the hand that once fed him with a goal against the Blues in St. Louis. Over the next calendar year plus, Lampman totaled 13 goals and 30 points in 49 NHL games, and he racked up 13 goals and 37 points in 35 games with the Clippers. But his promising career came to a sudden halt in a Dec. 3, 1976 collision with the Flyers’ Moose Dupont. Lampman suffered slippage of two of the vertebrae in his neck, an injury that required surgery and ultimately ended his career.

With their nineteenth pick – including the two netminders – in the expansion draft, the Caps grabbed one of the more experienced players they were able to procure, and another one who would not wind up cracking their opening night roster. Veteran left wing Lew Morrison was chosen from the Atlanta Flames, where he had played 130 games in the first two seasons of that expansion club’s existence. Morrison was originally the eighth overall pick of the Philadelphia Flyers in the 1968 NHL Draft. By the time the Caps chose him, he had amassed 332 games over five seasons as a bottom six forward and penalty killer. But he opened the season at AHL Richmond, returning to the NHL to make his Caps debut on Halloween night, 1974 against Montreal. By Christmas, Morrison was gone, dealt to Pittsburgh for Ron Lalonde in a trade that helped both clubs. Morrison finished his nine-year, 564-game NHL career with the Penguins at the age of 29. He had four assists in 18 games in his short stint with the Caps.

One source of the expansion Islanders’ woes in 1972-73 was the loss of nearly a third of the team’s expansion draft selections to the nascent WHA, which also began operations that season, raiding NHL rosters and farm systems with the lure of more money and opportunity. Washington’s only misstep in this regard came with its 20th overall pick, that of forward Steve West from the Minnesota North Stars. As the AHL’s leading scorer (50 goals, 110 points with New Haven) in 1973-74, West was an attractive pull for the Caps at that stage of the proceedings. But unbeknownst to Schmidt and the Caps, West had already committed to the WHA Michigan Stags. West never played in the NHL – the only one of Washington’s 24 expansion selections who never played in the League – but he logged 142 games scattered over five WHA campaigns before finishing his pro career at the age of 29. West is the father of Sommer West, who represented Canada in softball at the 2000 Summer Olympics and enjoyed a lengthy pro hockey career of her own in the NWHL and the CWHL.

Next, the Caps chose blueliner Larry Bolonchuk from Vancouver. The Canucks’ fifth-round choice (67th overall) in the 1972 NHL Entry Draft, Bolonchuk got his NHL wet in a 15-game trial with Vancouver as a 20-year-old in ’72-73. Bolonchuk was the youngest player the Caps selected in the expansion draft, and he did not crack the roster of the inaugural ’74-75 debut. Bolonchuk debuted with the Caps in their sophomore season of ’75-76, getting into one game and collecting an assist. He skated in 59 games with the Caps scattered over three seasons before becoming a free agent in June of 1978. Bolunchuk’s NHL career consisted of 74 games and his career ended at age 28 with IHL Dayton in ’79-80.

The Caps then chose defenseman Murray Anderson from Minnesota, the last of just six defensemen they selected among their 22 skaters in the draft. Originally drafted by the Canadiens in 1969, Anderson played for Calder Cup champion Nova Scotia team in 1972 and captained AHL New Haven in 1973-74. Anderson got into 40 games with Washington in the team’s first season, and that turned out to be the sum total of his NHL career; he notched one assist. He spent two seasons in the Caps’ organization and was finished with pro hockey before his 28th birthday.

With their penultimate pick in the expansion draft, the Caps tabbed forward Larry Fullan from Montreal. Signed by the Habs as a free agent after a strong collegiate career at Cornell – where he played under the legendary Ned Harkness for a season – Fullan erupted in his sophomore season as a pro, leading AHL Nova Scotia with 37 goals and 87 points in ’73-74. Fullan was second on the AHL Richmond club in scoring in ’74-75, earning a brief promotion to the Caps late in the team’s first NHL season. Fullan’s NHL career lasted just four games, but he did contain one memorable highlight. On March 1, 1975 at Maple Leaf Gardens, Fullan scored his first – and only – NHL goal on a Washington power play, doing so in his hometown of Toronto. A night later, he played his final NHL game. Fullan retired from the game in 1976 at the age of 27.

After Kansas City made its final pick by choosing forward Doug Horbul from the New York Rangers, the Caps concluded the expansion draft by also selecting a forward from the Rangers, veteran NHL winger Jack Egers. Known for possessing one of the hardest slap shots of that era – and nicknamed “Smokey” because of his shot – Egers started his NHL career with the Rangers in 1969-70 before departing for St. Louis in a six-player swap in November of 1971. With the Blues, Egers put up consecutive 20-goal seasons before he was returned to the Rangers in a decidedly more minor deal less than two calendar years later. Egers’ NHL peak was plagued by injuries; he suffered a serious concussion in which he temporarily swallowed his tongue and needed trainers to save his life. Egers also endured a separated shoulder, wrist surgery, and bone chips in his left knee, which also required surgery. By the time he arrived in Washington, Egers’ back was acting up; he had two spine surgeries during the Caps’ first season, and the back ailment eventually ended his career prematurely at the age of 27. Egers was in the lineup for Washington’s first-ever game and just over a week later, he delivered the first game-winning goal in Caps franchise history on Oct. 17, 1974. It was one of six goals Egers scored in 26 games in a Caps sweater, scattered over just 26 games in the team’s first two seasons of existence.

With the expansion draft in the books, Schmidt and Abel politely spoke of the process and the Caps’ selections, and he said all the right things.

“I think we did the best we could under the circumstances,” said Schmidt, as quoted in the June 14, 1974 edition of The Detroit Free Press.

“We’re very happy with Simon Nolet,” said Abel in the same story, reserving judgment on his other 23 selections. “He’ll be our goal scorer and he’ll certainly see a lot of ice time.”

The final paragraph of the United Press International piece reads thusly: “A highlight of the four-day meetings was the awarding of conditional franchises to Denver and Seattle for the 1976-77 season. Seattle was represented by Vince Abbey while Ivan Mullenix represented Denver.”

As we all know now, that intended expansion to Denver and Seattle never went down; within a year or so, the NHL put the brakes on its ambitious plan to expand to 24 teams by the end of the 1970s. And as we also know now, the Caps and the Scouts were both miserable NHL franchises for the better part of a decade. The Scouts last just two seasons in K.C., moving to Denver in ’76-77 and then to New Jersey after six mediocre seasons in Colorado. The Scouts/Rockies/Devils franchise tasted the playoffs after its fourth season – its second season as the Colorado Rockies – but that was its lone postseason appearance in its first 13 seasons of existence.

Of the 27 expansion teams added to the NHL since 1967, none had a worse record than Washington (8-67-5) in its first season. The Caps are also the only one of those 27 expansion teams that did not reach the playoffs at any point in its first eight seasons of existence. None of those 27 expansion clubs had a worse points percentage (.304) over its first eight seasons than the Kansas City/Colorado entry; the Caps are next-to-last at .334. The ’74-75 NHL expansion produced both of the worst of the 27 teams the League has added in the last 57 years.

Kansas City’s expansion draft resulted in the selection of players who had combined for just 79 goals in the previous NHL season, paced by Nolet’s 19. Schmidt and the Caps selected players who combined for just 40 NHL goals in ’73-74.

Schmidt’s post-expansion draft actions also spoke loudly. A week after the draft, he purchased 40-year-old veteran defenseman Doug Mohns – who would eventually become Washington’s first captain – from Atlanta. A month after that, Schmidt cajoled longtime NHL forward Tommy Williams – one of the few Americans to hold down a regular NHL gig in the 1960s – to leave the WHA New England Whalers for Washington as a free agent. And two days after securing Williams’ services, Schmidt purchased forward Bill Lesuk from Los Angeles.

All three players were well known to Schmidt from his Boston days. The toupee topped Mohns was a teammate of Schmidt’s with the Bruins in the early 1950s, and Schmidt later coached the blueliner in Boston. Williams also played for Schmidt when he coached the Bruins, and Lesuk was signed by the Bruins during Schmidt’s tenure as GM in Beantown.

It’s hard to imagine, but the Caps might have been notably worse without that trio of veterans added later in the summer of ’74. Mohns played in 75 of Washington’s 80 games and was second only to Labre in scoring among the team’s defensemen. Williams led the expansion Caps with 22 goals and 58 points, and Lesuk led Washington with 79 games played that season. Aside from Low and Labre, the expansion draft provided the Capitals little in the way of dependable, regular NHL players who could provide a stable foundation for an expansion club to build around.

Of the two dozen players the Caps chose in the 1974 NHL expansion draft, exactly half lasted less than a calendar year in the Washington organization. Eleven of the 24 suited up for the Caps’ first ever game, and only one – Labre – was still in the organization at decade’s end. The 24 players combined to play 2,401 games in the NHL, a paltry figure that led to a revolving door of players, coaches and managers for the first eight seasons of the team’s existence.

These days, NHL expansion is a veritable baby shower of lavish gifts that enables the League’s newest teams to be competitive right off the hop. Vegas needed only four seasons – the last two of which were truncated by the pandemic – to easily exceed the win totals amassed by both Kansas City/Colorado (140) and Washington (163) in their first eight seasons in the League. Seattle made the playoffs in its second season in the circuit.

Excluding Vegas and Seattle because those franchises haven’t been in the League for eight seasons yet, Edmonton is the most successful NHL expansion franchise over its first eight seasons in the League (.635 points percentage). Along with Philadelphia and Vegas, the Oilers are one of only three teams to win the Stanley Cup during their first eight seasons of existence.

The expansion Oilers joined the NHL in 1979-80 along with three other teams as part of a merger with the WHA, and their instant success is due to the presence of one Wayne Gretzky on the roster. Buffalo (.558) is the second-best NHL expansion teams through eight seasons; the Sabres had the good fortune of pulling franchise center Gilbert Perreault in their first ever amateur draft. Even with their rugged first season results, the Islanders (.550) are the third-best expansion club; they snagged franchise blueliner Denis Potvin in their second amateur draft and grabbed future Hall of Famers Bryan Trottier and Clark Gillies in their third amateur draft.

Expansion teams that were able to secure a young foundational player to build around – like Philadelphia with Bobby Clarke – were able to climb their way to contention and being competitive much more quickly than teams like the Caps and the Scouts. The expansion draft offerings were paltry enough, so it didn’t help matters for Kansas City or Washington that the 1974 and 1975 amateur drafts were the worst two of the 1970s; both produced the lowest percentage of NHL players of the decade and the ’75 Draft produced the shortest average career of drafted players in the decade.

The Caps and Scouts spent $6 million each for the privilege of drafting a couple dozen eager but ordinary – at best – players who provided the shaky foundation for those two franchises half a century ago, but success was elusive early and a long time coming for both sides. The stifling and ongoing struggles of the Caps and Scouts from the outset of their existence – as well as the financial and other woes suffered in Oakland, Pittsburgh, Cleveland and other NHL cities of that era – became a lesson for the League, which eventually squelched plans to expand any further until the merger with the WHA brought four new teams into the League in 1979. After the merger, the NHL remained a 21-team circuit until the addition of San Jose in 1991.

With expansion entry fees in the $600 million range these days, the NHL now realizes it must ensure that new clubs are competitive immediately, and so they are. That realization came decades too late to help the Scouts and the Caps, but those stories both have happy endings. After bouncing from Denver to the swamps of northern New Jersey, the former Scouts reached the mountaintop first, winning the Stanley Cup in 1995, the first of three Cup championships in a decade. Once they settled in New Jersey, the Devils were able to find stability under the leadership of longtime GM Lou Lamoriello.

Here in Washington, long term stability eventually turned the tide as well. The only expansion team ever to miss the playoffs for each of the first eight seasons of their existence, the Caps have the NHL’s second-best regular season record since 1982-83 (.573) among the 21 NHL teams that have been in existence throughout that time span. The Caps’ version of Lamoriello is Dick Patrick, the team’s longtime president who helped save the team in the summer of 1982 when it was on the verge of folding, merging with another team, or packing up and moving to another location.

Forty-four years to the day after Schmidt did his level best to get the Caps off the ground, the team celebrated its first Stanley Cup championship with a memorable parade in downtown D.C., an event witnessed by tens of thousands of jubilant onlookers. Although it took longer than Schmidt or anyone else expected or wanted, the 2018 Cup championship was well worth waiting for in these parts.

As the great Bruce Springsteen once posited in musical fashion, “From small things mama, big things one day come.”