The debate about whether or not to go public didn’t last long

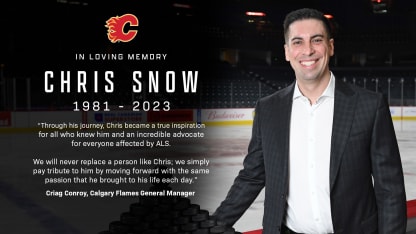

Within weeks of receiving the traumatic, life-changing diagnosis, Chris Snow turned the pain, the fear, the uncertainty of it all into an incredibly noble pursuit.

“I remember him and I sitting in the office and I asked if he was going tell anyone,” said Flames GM Craig Conroy, reflecting on the incredible life of his cherished teammate. “I asked him, ‘Are we going to tell the office?

“He said, 'I'm debating it ... but I want to tell it in my own way.'

“He marched in one day and said, 'I'm going to tell everyone, Craig. My mission is to do something about the disease and I'm going to try my best to make that happen.'

“The strength it takes to do something like that is something you can't even put into words. He really believed that they were going to find a way to cure this thing, and that was his goal from that point forward.

"We're not there yet. But we’re closer now than we ever have been.”

The Flames Assistant GM quite literally changed the world, creating a legacy that will live on far beyond the walls of the Scotiabank Saddledome. He defied the odds and fought valiantly not just for himself, but for his kids, Cohen and Willa, his remarkable wife, Kelsie, and the countless others that were affected similarly, but no longer had a voice.

The cruelty in ALS is that, while the disease rapidly takes hold and grinds the basic, bodily functions down to a crawl, it takes an immeasurable, psychological toll on family and friends, and unforgivably prolongs the suffering. And this was an illness that already claimed the lives of Chris’ father, his cousin and two uncles, all within 12 months each.

Chris, too, was given only one year to live, but he defiantly said no, willing himself to another four-and-a-half years of birthdays, holidays and indelible life moments before he was tragically taken from us on Saturday.

Sometimes, he would go days – if not weeks, and months – without experiencing any significant changes in his condition.

Until the day he woke up and the weakness in his right arm had devolved into something more alarming. Or when that famously bright smile of his began to fade, before losing it completely over time. Or when eating and drinking had become too much of a challenge, and dressing himself, driving, and living an independent life was no longer possible.

But live, he did.

He remained active and outfitted his bicycle, golf clubs, hockey stick and baseball bat with a custom grip so he could still do the things he loved with his family. He cannonballed off docks at the Snow’s ‘Happy Place’ in New Durham, New Hampshire, coached little-league, and even crossed a once-‘impossible’ mile marker – his 40th birthday – by throwing out the first pitch at a Boston Red Sox game.

“When you talk about people looking at him as inspiration, I don’t know how you can’t,” said Flames Head Coach Ryan Huska, who revealed that Chris was one of his biggest supporters in helping him land the top gig. “Never did he have a bad day, considering what he was going through. And he continued to do his job to the best of his ability every day."