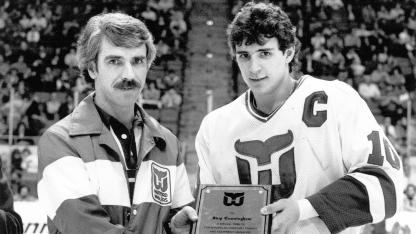

RALEIGH, NC. -Long after Mark Howe was done playing in Hartford, the Hall of Fame defenseman would still call Skip Cunningham looking for a special helmet liner that he knew the venerable equipment manager could put his hands on.

Long-time NHL player and national broadcaster Ray Ferraro, who first met Cunningham as a 20-year-old member of the Hartford Whalers, made a similar call before one playoff season looking for discontinued shin guards to replace his old rotting ones.

Burnside: The Unrivaled Importance of Skip Cunningham

"Who has had more of an impact on the organization than Skip Cunningham?"

"He said, 'I think I've got some in the equipment room.' And I ended up with new shin pads," Ferraro said.

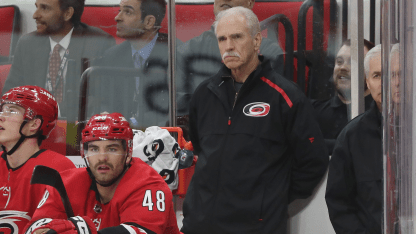

When Rod Brind'Amour took over as head coach of the Hurricanes in 2018, he begged the long-time equipment manager not to retire.

"When I got the job he was considering retiring," Brind'Amour said. "I said, 'you've got to stay on. You're just so important to everybody in that room.'"

"I think he reluctantly agreed," Brind'Amour added with a laugh.

Snapshots of a life dedicated to an often thankless but critical part of the game.

And maybe, just maybe, these snapshots help describe Cunningham's vital role with the Hartford Whalers/Carolina Hurricanes franchise. But the truth of the matter is they are just that, snapshots, and as such will only just scratch the surface about one of the quiet icons of this franchise and the game itself.

Skip Cunningham?

The guy with the distinctive mustache and the fierce look who appeared often in photos and television shots of the Hurricanes' bench during games for almost a quarter of a century?

"He's probably one of the most important people in the franchise's history, to be honest with you," Brind'Amour said. "Just the impact he had on so many people. Who has had more of an impact on the organization than Skip Cunningham? Really."

Added Ferraro, "you cannot be around anything for that long without being a really great person. It was his job and he did it amazingly well and he was so enjoyable to be around."

Cunningham's house when he was growing up was backed onto the left field of the Northeastern University Athletic Field in Brookline, Massachusetts and it became like a second home to Cunningham.

"I was just a field rat," said Cunningham.

As he got older Cunningham met and ended up working for Jack Kelley, the legendary Boston University hockey coach, as the team's equipment manager. He performed similar duties with other collegiate sports programs including football and his first love, baseball, but it would turn out that hockey would become his calling and his life's work. He retired from the only job he ever knew prior to the 2020-21 season.

Cunningham received a degree in correctional practices at Northeastern and the year he graduated was the year the New England Whalers started in the World Hockey Association (WHA). Kelley had been hired as the team's first GM and it seemed natural that Cunningham would join the Whalers, too.

Before settling for good at the Hartford Civic Arena, where they would play until moving to North Carolina in the summer of 1997, the Whalers played games at Boston Garden, Boston Arena, where Northeastern still plays (it's called Matthews Arena now), and in Springfield when Boston Gardens wasn't available to them during the WHA playoffs and while the new arena in Hartford was being built.

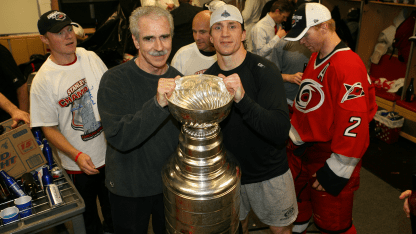

Cunningham would honor all of those stops during his day with the Stanley Cup after the Hurricanes' seminal Cup win in 2006.

In those early days, there was a medical trainer and an equipment manager. They handled everything from stick tape to sutures.

They packed all the gear they needed to go to the airport or from the practice rink to the main rink in a van.

Now there's a box truck with a 20-foot packing area, if not larger. And there's a staff of six or seven making sure that everything gets where it needs to go and is placed properly when it gets there.

When it was confirmed the Whalers were done in Connecticut early in 1997 and ultimately it was announced the team was headed to North Carolina, Cunningham recalled being given a weekend to decide if he was going to join the team.

It wasn't a hard decision. It was a job and he needed to work.

"I'd done it for a long time so I just made the decision," Cunningham said.

The team spent a lamentable two seasons playing out of Greensboro while the team's current home was being built in Raleigh. Cunningham spent those first two seasons shuttling between corporate housing condos in Greensboro and Raleigh.

A bare-bones training and equipment staff, a different location in a different city for home games and practices plus the regular NHL travel demands made the transition to a market that wasn't used to the game difficult, to say the least.

"It was brutal," Cunningham said.

"It wasn't so much being nervous, but you were playing 82 road games," he added. "That was just brutal on everybody. Greensboro was not great."

The team settled into its new home in Raleigh after those two years in Greensboro but overall it took Cunningham seven years to actually buy a house in the Raleigh area.

The standing joke was he was living in denial believing that one day he would show up for work and be told the team was moving back to the northeast.

Now Cunningham has two homes. The home of his roots is in the Boston area, where his daughters and some of his five grandchildren live, and the Raleigh area, where his son is a police officer in Raleigh and where he has put down his own significant roots.

As an athlete so much of life is in patterns and schedules and routines. Helping players stay true to those patterns and schedules and routines fell for years to Cunningham and the rest of the training and equipment staff.

"He understands because he's been around it since Gordie Howe," Brind'Amour said.

That's not a figure of speech.

In those early days of the WHA, the Whalers' roster included future Hall of Famers Gordie Howe, Mark Howe, Dave Keon, and briefly Bobby Hull. They weren't just icons, though, they became colleagues and friends to Cunningham.

So it would be Raleigh, too.

Brind'Amour arrived in Raleigh at the start of a snowstorm in January 2000 having been traded literally with the clothes on his back from Philadelphia while the Flyers were playing in Pittsburgh.

Hall of Fame defenseman Paul Coffey told Brind'Amour about Cunningham and how good he was with skates (even though Coffey didn't let anyone touch his own skates).

"So I went right to Skippy," Brind'Amour said. "You realize right away what a great guy he was. He was a father figure with all the guys."

It would be the start of something enduring and special.

For all of the technical advice and knowledge of the inner workings of the game Cunningham possessed, Brind'Amour remembers the long discussions about family and raising children. At one point Brind'Amour's oldest son, Skyler, who is now playing Division I hockey at Quinnipiac, was a fine baseball player and so Brind'Amour and Cunningham spent lots of time talking the intricacies of baseball and what a future in that sport might look like.

"He's a very smart guy, too, in regards to the hockey stuff," Brind'Amour said. "Just the everyday rigors of it, he knows what you're going through. And he's been through lots of stuff himself. Everybody has their stuff, right? And he's been through it. That's the relationship we had. He knew everything."

"He really cared about you and your family," he added.

Although he saw every single coach in Hartford and Carolina come and go, Cunningham remains closest with Brind'Amour.

"He's just unbelievable," Cunningham said. "He's just a phenomenal person and very organized. And the team reflects that."

"Each coach is different," Cunningham added. "I got along with all of them very well. You have to work together."

Justin Williams likewise met Cunningham very early in Williams's first stint with the Hurricanes, having also been traded from Philadelphia on the morning of Jan. 20, 2004, and arrived in time to play for the Hurricanes that night.

"Skip was the first person I met from the equipment staff," Williams said. "He was just exactly who is he today, 20 years ago; what do you need? What do you need from me?"

One of the highest compliments that can be given within a hockey team?

"He's a guy you want to sit with for a team meal or at a team function," Williams said. "Lots of really, really good stories that I always loved to hear."

There isn't one Cunningham moment for Williams but just the vibe of being in Cunningham's old office at the team's ramshackle old practice facility and having a coffee while his skates dried or just wandering in and sitting and listening as the stories flowed.

That vibe was in direct contrast to the fiery disposition Cunningham revealed during heated battles, especially in the playoffs.

"He would be so involved in it with us," Williams said. "I remember in the final (in '06) him barking at Raffi Torres. There's something to be said for a guy that cares that much and is on your side that much. He was pretty inspirational to be quite honest."

"It's tough to find the words that describe that kind of commitment and dedication," Williams added.

Cunningham makes only a passing nod to an apology for his fiery nature when it came to the games.

"I'm maybe a little more vociferous than I should be," Cunningham acknowledged with a laugh. "Some of that Boston comes out of me. I'm not backing down."

There have been situations with officials over the years and there was the time Cunningham got into it with long-time coach Jacques Demers on the Whalers bench when Demers was coaching the Indianapolis Racers in the WHA.

"He had one of our goaltenders in a headlock," Cunningham said. "So I grabbed him."

Sounds fair.

Ferraro recalled a Whalers game against Boston when Jay Miller was Boston's resident enforcer.

"And Skip's yelling from behind the bench at Miller. He's yelling, 'You'll get yours, Miller. Try Kleinendorst. Try Kleinendorst,'" Ferraro said referencing defenseman Scot Kleinendorst, who passed away in late 2019.

"Scoty's like, 'what?'" Ferraro said laughing as the bewildered Kleinendorst understood that he was now going to have to engage with Miller thanks to Cunningham's exuberance.

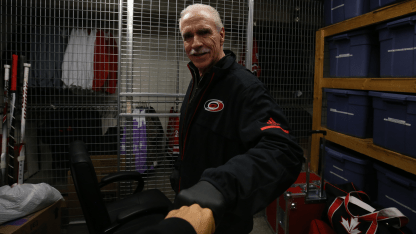

That was the obvious part of Cunningham's presence. But so much of his presence was subtle in nature and you would see it every time you walked into the Hurricanes locker room before the players arrived.

There is something pristine, almost beautiful about an empty NHL locker room before the players arrive. Almost like the empty ice after the Zamboni has left it. Full of promise.

That locker room is Cunningham's domain.

"Every stall is set up the same way," Cunningham said.

Shin pads here. Gloves here. Helmet there. Same from player to player.

Each team may have a different set-up for the gear but each team's locker room will look the same in terms of its consistency.

"Some guys are pretty good at placing the stuff after a game," Cunningham said. "Some guys it takes a long time for them to figure it out. Especially if they've come from another team."

Add into the equation if a team is switching jerseys from game to game that will mean making gloves, pants, and helmets are all the right color and in their right place.

Darren Granger is the president of the Society of Professional Hockey Equipment Managers (SPHEM) and has been with the Los Angeles Kings since 2006. Before that, he held the equipment manager role in Vancouver.

Granger recalls the routine of Vancouver coach Rick Ley and GM Brian Burke, both of whom had strong connections to the Whalers, always included a stop to see Cunningham whenever the Canucks' path would cross with Whalers and then the Hurricanes. Every time.

And it was also routine for the visiting training and equipment staff to stop by or receive a visit from Cunningham.

Make no mistake there is a bond that extends from locker room to locker room for the men and women who hold down these jobs.

"What we all do in our jobs is we do the absolute best for our teams and I think of Skippy, for that long of a time, and the commitment it takes," Granger said. "You miss a lot of things and commit to these long seasons. We are really close. And all of us that do this job think very highly of each other."

"Just tapping into a guy like Skip's knowledge," Granger added. "He's seen so much in the profession and I really remember the times when Skip would come over when we were in Carolina and just talk. You listen to what he has to say."

Like players, there is a code among the equipment and training staff that no matter whose rink you're in, if you need something you're going to get it just as quickly as possible whether it's a helmet, screws, shoulder pads, or whatever.

"You reciprocate all the time. If I've got it, you can have it," Cunningham said.

In some ways, the job done by Cunningham and his colleagues takes the game down to its most basic. Skates, sticks, helmets, all the rest of the gear. Get them right and the rest, well, that's on the players and coaches.

Cunningham has seen it all, from David Keon's old-fashioned wooden, straight-blade model of stick to the complex composite materials used in the sticks now. That and every other advancement or gadget as it related to equipment and the like has come across Cunningham's watchful gaze.

"He's seen all that," Williams said. "He knows when to roll his eyes and when something is actually innovational and unique. You definitely take his advice on these types of things for sure."

Sometimes Cunningham would notice that as a player aged, he might play more vertically, standing up straighter, which might necessitate a different lie or type of stick.

Cunningham would examine the wear pattern on players' sticks to make sure the correct lie or type of stick was being employed. Sometimes he'd ask other players for their opinion on a stick's usefulness or lack thereof.

If a blade shows wear on only half the blade, "it's telling you you're not using the whole blade of your stick," Cunningham said.

He recalled how Brind'Amour would use some of Eric Staal's sticks and shave the blade using a belt sander to get the depth he wanted.

He recalled Brendan Shanahan using an old fiberglass stick and going through three to five shafts a game. "He was too strong for what he was using," Cunningham said. "It was completely bent."

Each player with his own needs and personality. Multiply that season by season for decades. It's almost too much to comprehend.

"That job's demanding, right? And everybody needs everything five minutes ago. And Skip, he got it all done. It was on Skip's timeline which was the right timeline. It was just fun to be around," Ferraro said.

"Just think about how many times in Skip's career you land on the road or at home games for that matter. The guys (the players and coaches) are going to the hotel or they're going home and they go to the rink the next day and I'm expecting my gear to be dry and to be hung up because that's just the way it is," Ferraro said. "And you don't think that took them three hours to set up this room and we've only been away from the rink for 10 hours."

"They players know, they just know," Ferraro added. "They're beyond invaluable and then when they're amazing people like Skip I mean Skip's an amazing guy."

There are moments, of course. Too many to count really.

His teams in Hartford, and then in Carolina, experienced all kinds of highs and lows, including crushing playoff defeats, sometimes in Game 7s.

"You understand how many factors are involved," Cunningham said.

There was a memorable Game 7 between Hartford and Montreal in 1986 won by a rookie netminder named Patrick Roy. The Habs, who would go on to win the Stanley Cup.

"Those are franchise-changing things," Cunningham said.

There was the 2002 Stanley Cup final and how Hall of Famer Ron Francis, now the GM in Seattle, missed a golden opportunity in Game 3 that would have given the underdog Hurricanes a 2-1 series lead. Detroit won in triple overtime and won the series in five games.

But Cunningham also recalled how it was Francis who scored the game-winning goal in Game 1 against the powerful Red Wings.

Francis mounted that puck and gave it to Cunningham as a keepsake.

The great yin and yang of hockey.

"You don't forget those things. The chances. You remember the chances you had," he said.

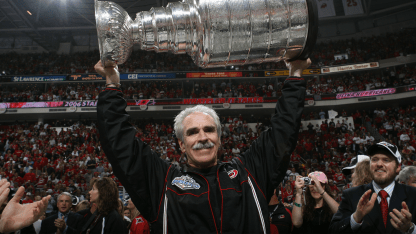

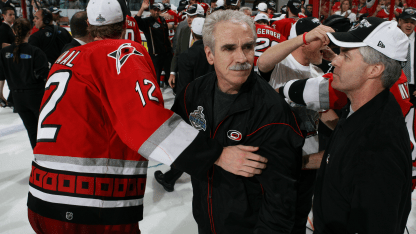

And then, of course, to have been there when it all came together in 2006 in Game 7 at home in Raleigh and the Cup on the ice and then in the locker room.

The most memorable moment?

After the families had been ushered out of the locker room and it was just the team, the players, the coaches, and staff.

A few moments to reflect and share in the moment.

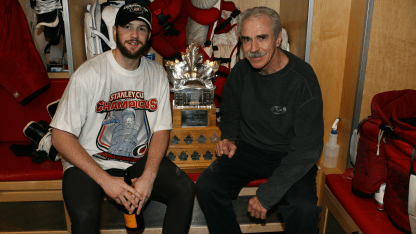

"I can remember sitting with Cam Ward at his stall and the trophy was right beside him," Cunningham said.

"That was the first time you felt, what really just happened?" Cunningham said. "And sharing with the guys, just the guys and the immediate staff. That's when it really first hit me what we'd finally done."

"I remember that moment," Ward said in a recent interview.

"I actually gave Skippy my Stanley Cup-winning glove." "If you ever get a chance to go to Skippy's house he's got an amazing memorabilia room. He's got a lot of stuff," Ward added.

"I thought then, at an early age, and still do, I thought that highly of Skippy," Ward said. "He was a great man."

There are pictures scattered in the press box hallway and throughout PNC Arena of that Cup win.

"The best pictures are of guys like Skip holding the Cup. It brings a smile to my face every time I see it," said Williams who remains with the team as a special advisor to GM Don Waddell. "I don't have one bad thing to say about him. He was unapologetically him every day."

And on Cunningham's day with the Cup?

An ode to his past and his love for the community.

"I had a fabulous day with the Cup," he said.

A visit to a children's hospital in Hartford, lunch in Springfield, and then to Boston to Fenway Park where he took the Cup up into the Green Monster and then sat it next to the World Series trophy. At one point Cunningham had a nice chat with David Ortiz who was especially impressed with pro sport's greatest trophy.

Cunningham is a father to three and grandfather to five. Two daughters still live in Connecticut so he's there a lot helping out with the grandkids. And he has a son, who once played stickball with a tennis ball with Paul Coffey at the 1986 All-Star Game in Hartford, who is a police officer in Raleigh.

He's dropped by the rink a couple of times since retiring and of course, he is always welcome in the room he presided over for so many years. "I don't miss going to bed from 3 to 5 o'clock in the morning,' Cunningham admitted. "I do miss the interaction with the players that's the one thing you miss without question, every day."

Worth A Click:

2022-23 Single Game Tickets

Cam Ward Named To Hurricanes Hall of Fame

Vote Now For The Canes 25th Anniversary All-Time Team

Sign Up To Watch Carolina Hurricanes Hockey Through Bally Sports+

Canes 2022-23 Giveaway Schedule

Canes December Schedule